MATCAxC4 JOURNAL: Conversations Around Photography, Vietnam & UK

A series of articles discussing various aspects of image-making. Supported by British Council Vietnam’s Digital Arts Showcasing grant 2021.

????✍️??

Hoang Long’s photography career was off to a rough start. For a personal project in 2014, the fledging visual journalist set out to accompany and document a street kid in Hanoi over the span of six months – a purportedly rare opportunity for him to explore drastically different conditions of residents living in the same city. However, at the time, he was also employed for street children outreach and rescue missions at a non-governmental organization (NGO) office in Hanoi. Long did not report the project to his employer; it was entirely of his own volition.

Judging by the stringent code of conduct at the organization, Long violated multiple clauses, including failure to obtain a consent form and photographing a child in vulnerable circumstances. Long received his layoff notice shortly after his superiors found out, while his project is still left on hold to this day.

Long’s story calls to mind the significant role photography plays within the NGO sector – something that occurred to me during my stint in the field. Images depicting underserved people (to be) supported by development and charity campaigns are heavily employed by NGOs to call up public awareness and benefactors’ support, possibly thanks to the medium’s perceived objectivity and capacity to instantaneously deliver information and evoke emotional responses. In a larger context, there have been several occasions where photographs of victims serve as the driving agent for change owing to their impact on public opinion. Instances like the Napalm Girl or the image of Alan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian found dead on a Turkish shore, have prompted momentous responses worldwide, leading to swift policy decisions – a result hardly achievable through usual protocols.

Nonetheless, they are exceptions and not the rule. Faced with the saturation of photos highlighting suffering, the photography industry has been going through major overhauls – among them are calls to protect the subject’s dignity in reportage and reassess the actual impact of graphic representations of tragedies.

Both the nonprofit and photography sectors have adopted the term “empowerment”, an effort to shift the narrative in media towards the respective owners of the stories. Codified rules have also been established to deter certain conducts, namely invasion of privacy and taking photographs without the subjects’ voluntary, informed consent. Extra care should be taken when dealing with vulnerable people and groups.

Black-and-white as they seem, such codes of ethics in photography vary between different fields or even between organizations within the same field. Contexts have a lot of say in the process: Whether an act is right or wrong might be dictated by the power dynamic as well as the photographer’s intention and personal costs when making the work, which don’t always manifest in the image.

Coming back to Long’s case, he acknowledged not having complied with the social workers’ discipline during our conversation while also expressing regrets about the failure to shed light on street children’s harsh realities, a task he assumed for himself. As Long sees it, he let his personal feelings take over, which resulted in hasty decisions and conflicts between reporting and aid missions, between a social worker’s role and a documentarian’s. Eight years following the incident, Long says he still keeps in contact with the subject, even planning to pick up where he left off with the documentary. Yet, the final outcome is no longer his priority, as “the subject’s life is more important.”

Long has since been contributing to online news sites, creating photo series and short docs on marginalized groups in Vietnam: From the LGBTQ communities in Hanoi, elderly lottery vendors in Ho Chi Minh City, to victims of riverbank erosion in a Mekong Delta province. In self-reflection during and after each project, Long concludes that the subject’s trust should underpin all works; but it should develop organically with time rather than being chased after.

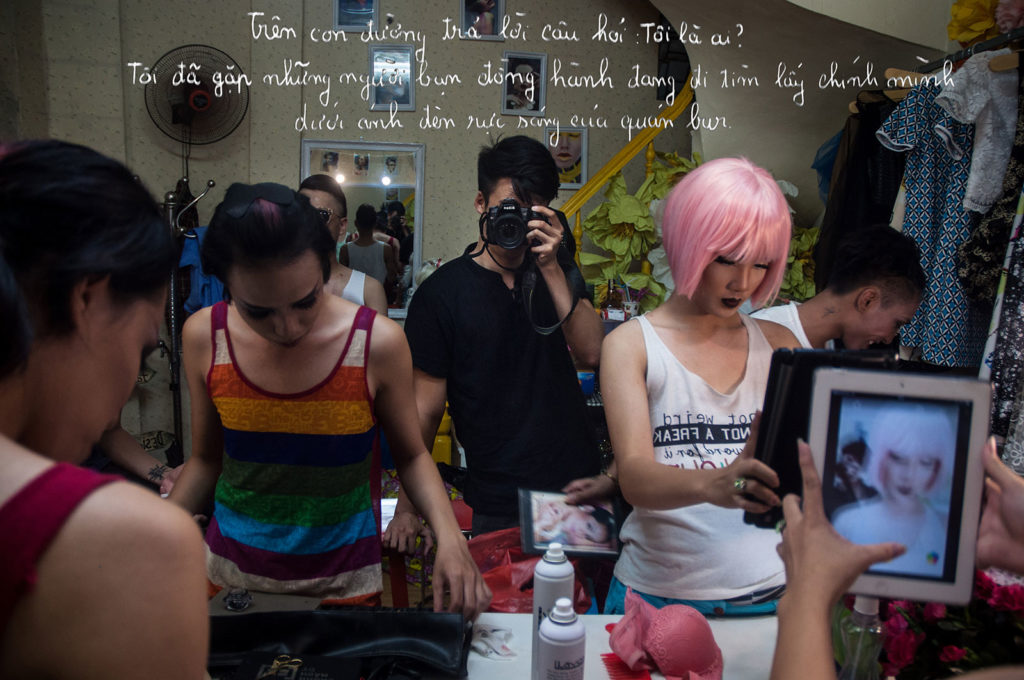

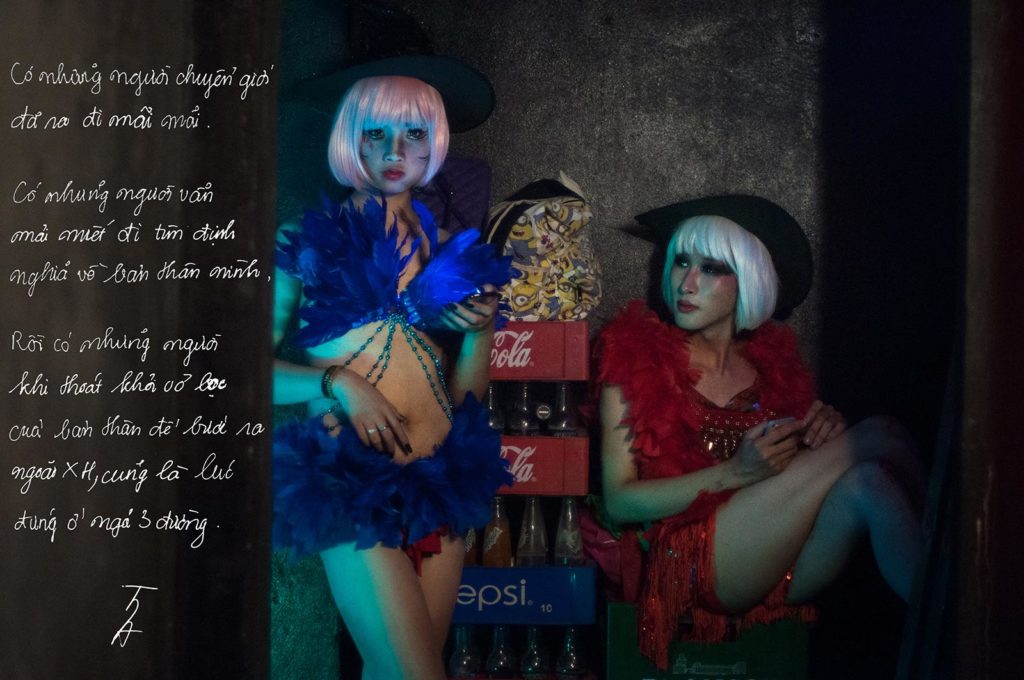

“These words might not be able to fully express my thoughts. The feeling of being a girl never subsides in me.” – Pretty Duy Anh, from Moments of Freedom (2015) © Hoang Long

Trust and intimacy manifest in Moments of Freedom (2015), his subsequent series about transgender drag queens in the Hanoi-based troupe Ruby Model. They perform mostly in nightclubs – one of few locations in the capital city that welcome diverse gender expressions at the time. Immersed in neon lights, the performers rock extravagant outfits and glam makeup – ways to proclaim their gender identity that are celebrated here but would raise eyebrows elsewhere.

As the stage allow the drag queens to express themselves, the photographs open up space for their innermost sentiments. Instead of forcing the story into the familiar “behind the limelight” narrative that casts a gloom over trans stories, Long invites his subjects to recount their experiences by handwriting on the prints. Moments of pride follow fatigue and even self-pity, but most importantly, there is strength in owning their truth. The final images resemble autographed postcards where each performer is nothing short of a star.

Similar to Hoang Long, Thinh Nguyen’s works stem from personal deliberation, amplified by the communities’ own need to voice their distress. Once admittedly “out of the loop” with politics, Thinh had a change of mind when seeing the impact of political power on himself and others. In 2016, he started following the journey of Vietnamese residents who found themselves in land acquisition disputes, sharing their stories in photographic and video forms on his Facebook page Chuyện của Thịnh. He calls his practice “an amateur artist’s social work”. Because of their overtly political content, his works have resulted in heated debates and conflicts with local authorities.

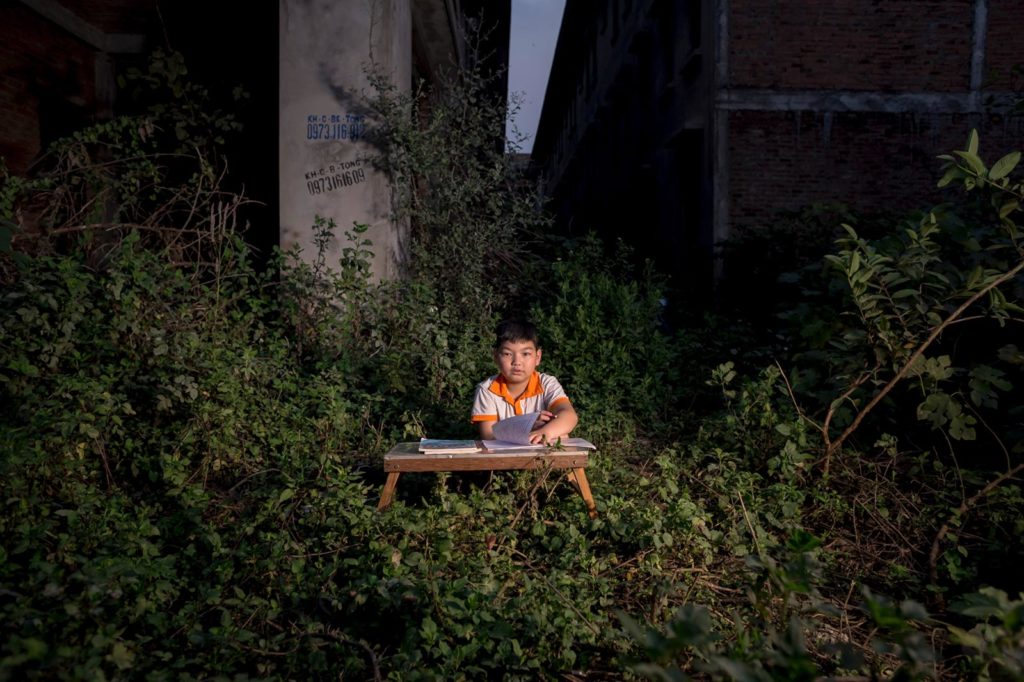

In his first photo series titled We Are Still Here (2016-2017), Thinh uses installation to disclose the plight of villagers left behind in rampant urbanization and the housing market bubble in suburban Hanoi. On the land they once called their birthplace, the villagers stand next to familiar icons of Northern Vietnamese countryside: farming boots, hoes, sedge mats and lacquered boards. Once the staples of a traditional lifestyle, these items now seem displaced in the desolate landscape of an abandoned infrastructure development project. The villagers look directly into the lens as if to question and challenge the gaze from the other side.

In his later efforts, Thinh switches to moving image and interview montages where the subjects, including social activists and families of prisoners of conscience, could speak up about their situations. He sees this as a way to resolve his self-proclaimed position of “having the upper hand”, meaning to document the pain of others despite not having firsthand experience. The medium has resulted in works with an apparent collaborative dimension. Moving image allows his subjects to express themselves with dramatic gestures, both with and without direction: shouting, frantically dancing or donning strange outfits in public – desperately calling public attention to their distress while avoiding potential censorship.

Visualizing injustice is no easy task: It calls for more than pointing the lens at the victims. What is benefiting from such inequality? Which apparatus is maintaining their “underserved” status? Is the one behind the camera aware of their own blind spots, biases and cliches? Thinh is yet to arrive at a definitive answer, but that’s why he keeps pushing his practice.

Both Thinh and Long position themselves as independent image makers – a role neither popular nor convenient, especially when it comes to documenting the underprivileged in Vietnam. On top of that, the entanglement of international-standard ethical reins has made photography fieldwork increasingly harder to navigate. British writer Colin Pantall has concisely conveyed this state of gridlock: “Think too little about the history theory and the danger is you make work that is unsound in many ways. Think too much about the history and theory and you run the risk of hitting a photographic block or paying so much attention to theoretical considerations that your work is of visual interest to only a very limited audience”.

To Long and Thinh, theoretical and visual approaches would mean little if we fail to delve into the root cause of the issue. It is easy to induce sympathy from viewers instead of scrutinizing issues in business models [of sand mining] and local governments’ responsibility, Long reflects on a feature story about a grassroots task force against illegal sand mining in Ben Tre province that he co-produced for a TV award show. Similarly, Thinh often harbors doubts about the social impact of his own works despite having taken immense personal risks to create them. In the end, the only thing he can guarantee is to create a space for issues willfully neglected by mass media.

Discussions on ethical practices often regard photographers as having the upper hand in the power dynamic. Yet, power is hardly one-dimensional. Both aforementioned image-makers are trying to draw attention to hidden problems, all while dealing with the lack of resources and even facing serious repercussions. Images don’t stand alone but are part of a specific process and context. This is the exact reason why discussions on ethics should reach photo editors, communication specialists, and the general public rather than being insulated within the photographers’ circle. It’s time we look past platitudes along the line of “a picture is worth a thousand words” to see them for what they are.