MATCAxC4 JOURNAL: Conversations Around Photography, Vietnam & UK

A series of articles discussing various aspects of image-making. Supported by British Council Vietnam’s Digital Arts Showcasing grant 2021.

????✍️??

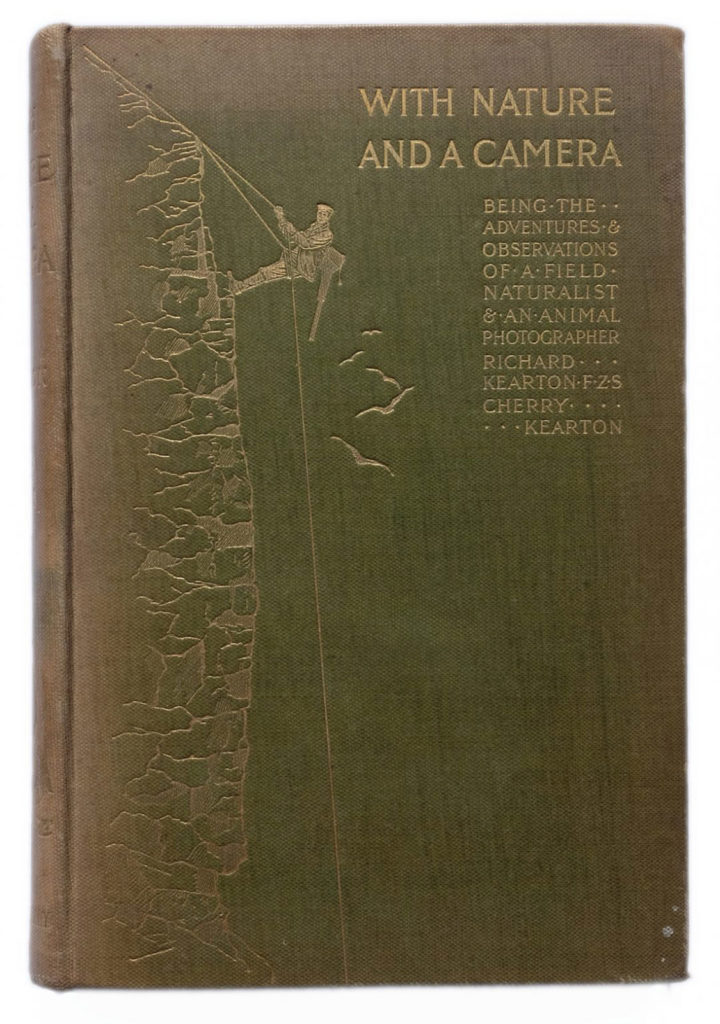

Every single creature in Richard and Cherry Keartons’ photographic archive is dead. Many of their kind living today are vulnerable, if not endangered. Oft-credited as the original nature photographers, their photographs are windows onto another time, where some of these species lived and prospered, images of what has passed. Such work may show history as a mirror to our modern day; it can not just remind us of what is lost, what has changed, or what we are losing, but also suggest potential for positive change. For, while many of us enjoy photographs for their aesthetic pleasure, the Keartons’ contribution to our history enters into science, politics, photography and beyond.

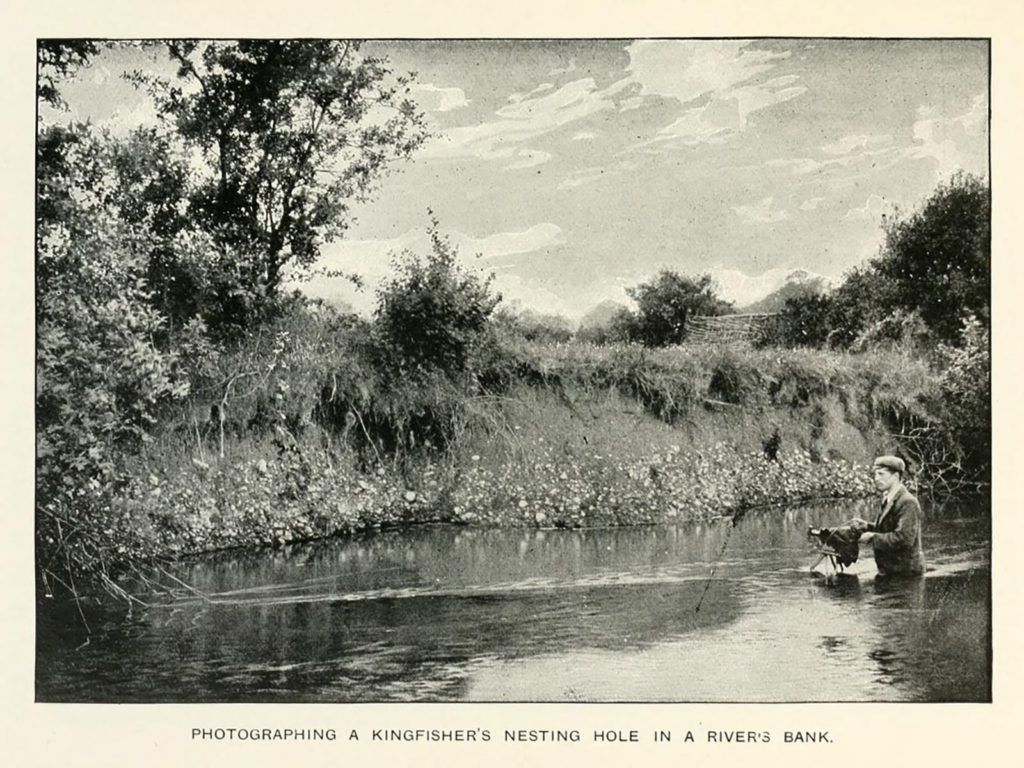

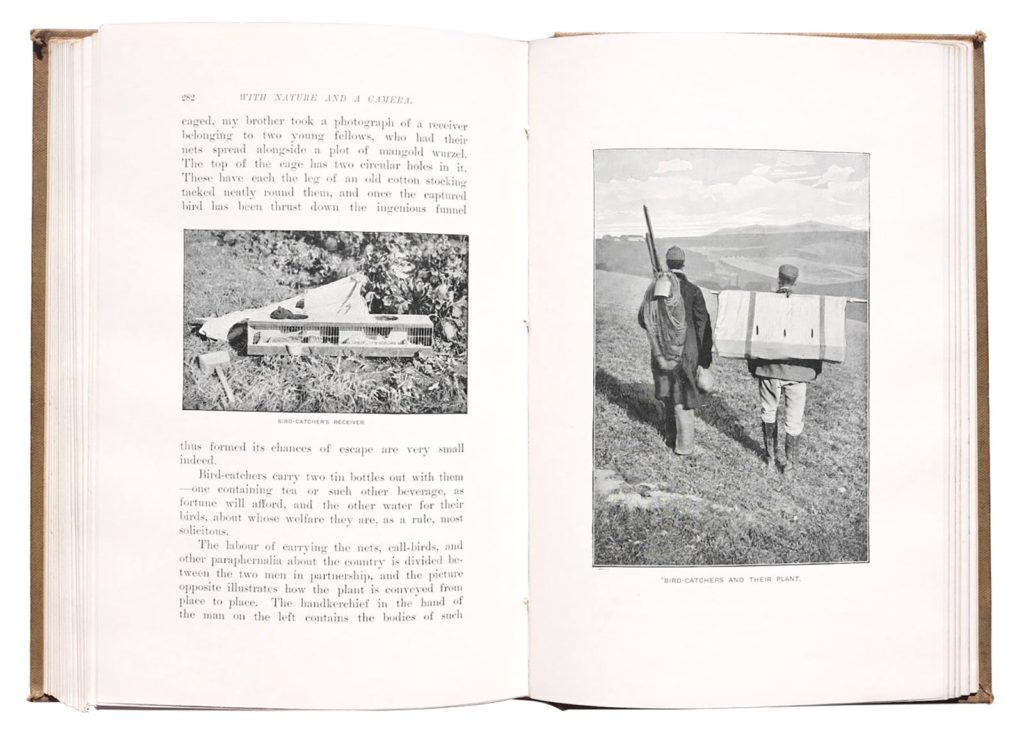

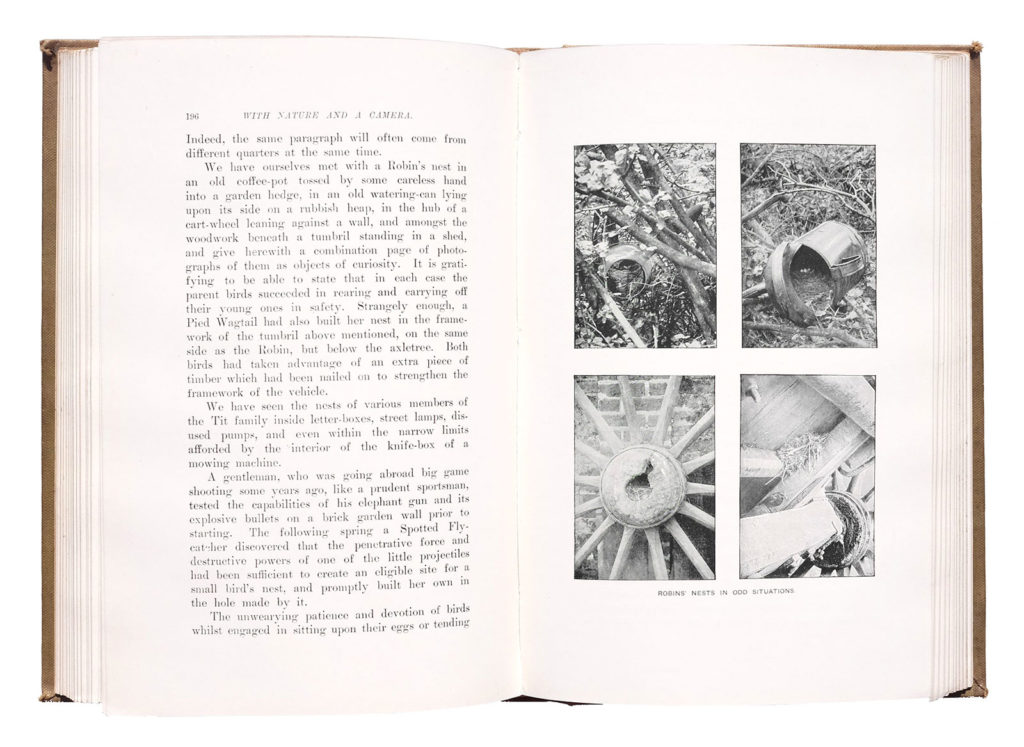

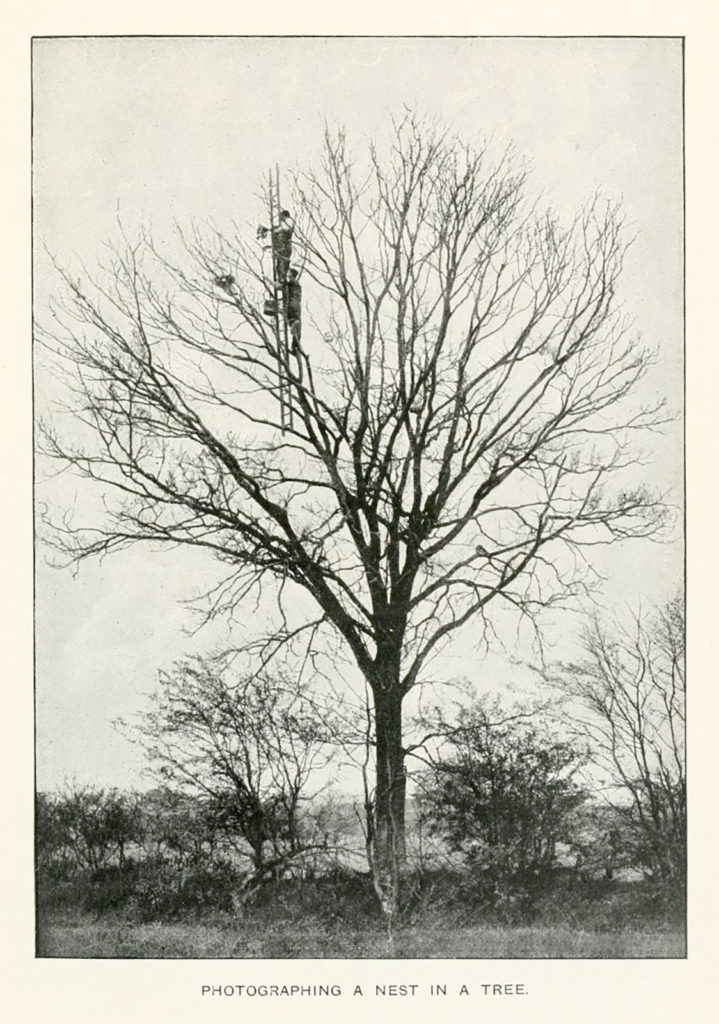

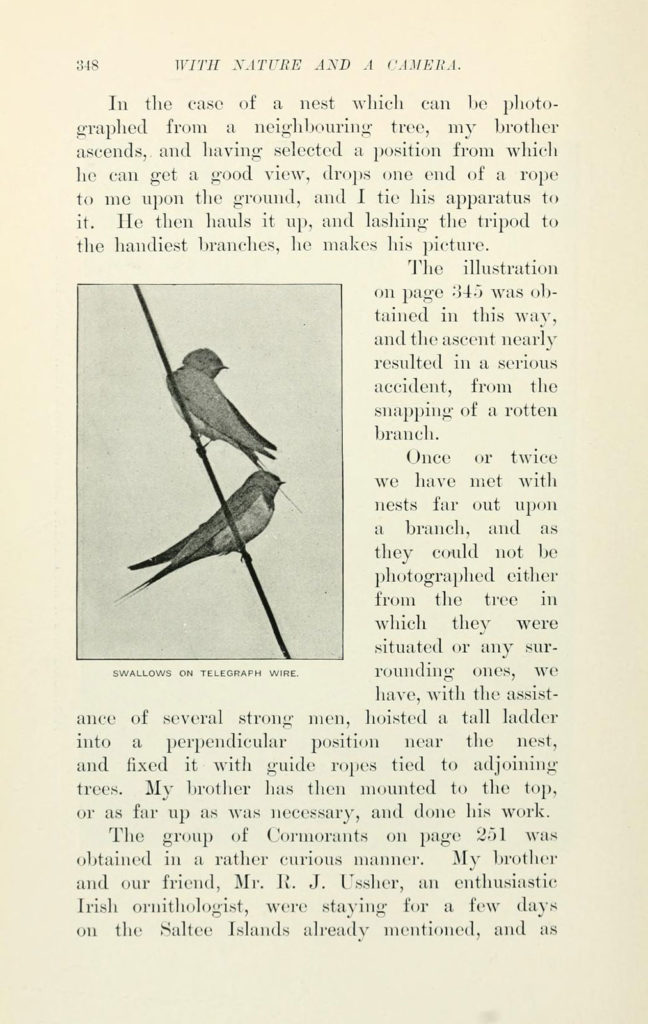

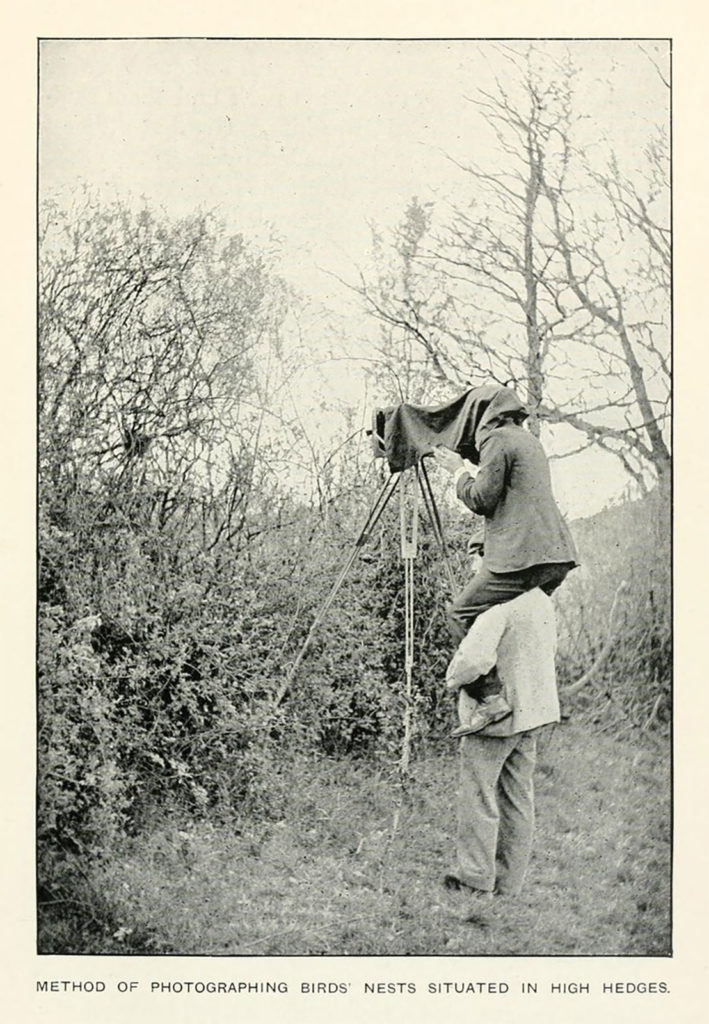

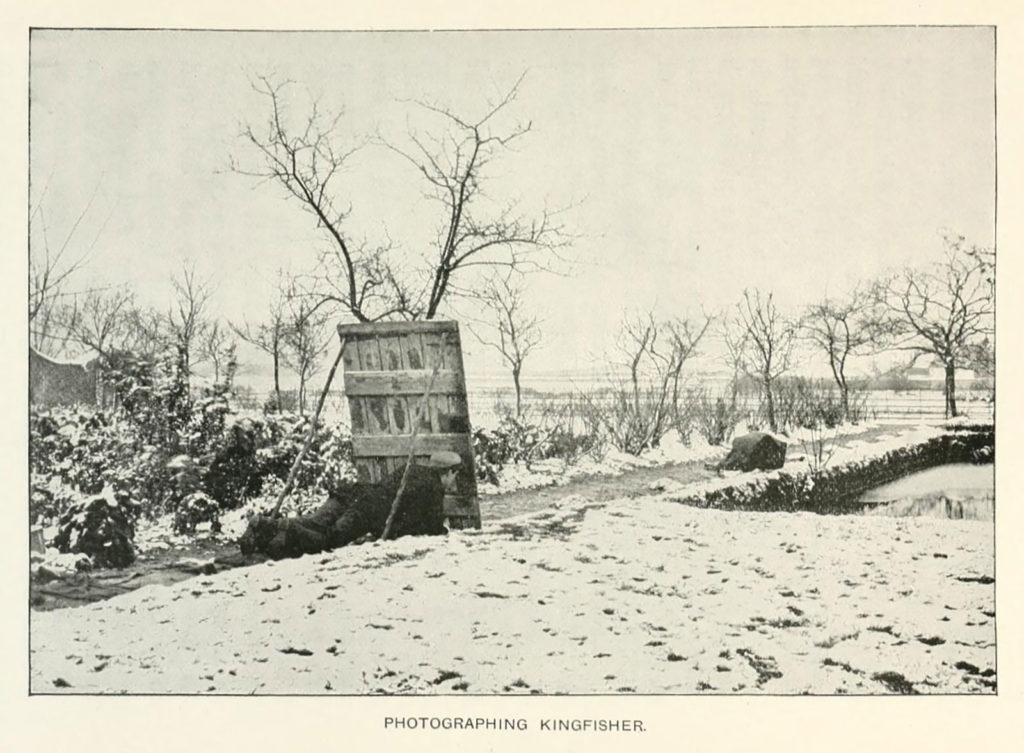

Born in Yorkshire, the Keartons used their pictures of the British countryside to encourage an appreciation of nature in generations of budding naturalists. Seeing the Keartons’ images cements how intentional this process was; it wasn’t about capturing a spectacular picture like a hunter (as many nature photography competitions encourage), but rather about a respectful acknowledgement. The elaborate hides the Keartons would construct is evidence of the lengths to which they would go to meet the natural world on its own terms; after all, they could easily poison or trap and then kill many species for posing, just like so many collectors would pin butterflies to boards. Instead, they achieved with patience extraordinary feats, including photographing a kingfisher, something regarded highly-challenging even today. The two conveyed the extent of their exertion in the 1899 book With Nature and a Camera, writing of their clifftop nest-hunting that:

Two of the nastiest sensations connected with the work are stepping backwards over the brink of a very high cliff into space and spinning slowly round like a piece of meat on a roasting-jack, and watching the sea chase the land and the land chase the sea upon becoming insulated through the crags at the top overhanging.

Richard & Cherry Keartons

For all the Keartons’ commercial motivations and their occasional sensational touch, their pursuit and sale of images was for the purpose of public education & appreciation, a love and admiration for the world beyond the image and beyond ourselves, often in our own immediate environment. Their use of on-site photography was intended to show reality as it was.

Our heritage has a role in our modern predicament, and has complicated our relationship with our current reality. Images play a crucial role in this. We quite understandably adore an idealised natural beauty, no matter the expense; rather, prestige has been our historical forte. For example, the international phenomenon of 18th-Century English landscape gardens – most famously those designed & inspired by Lancelot Brown – evolved to simulate natural land formations, and wealthy landowners would pay handsomely to create hills, rockeries and even “ornamental hermits” in the name of making their artifice as convincing as possible. Such gardens were built to resemble idealised images of the landscape, and acted as illustrations of nature in popular culture, and in the minds of those living in a rapidly industrialising world.

Since then, our relationship with images has helped to create a distance from reality, from the natural world as it really is. Many British people – particularly those of us living in the countryside – adorn our homes with representations of wildlife and various designs that reference nature, yet it is precisely this spiritual resource whose presence has been diminished by human activity, where even those green areas around our own homes, mowed short, can sustain little but ants and worms for the sake of appearances. In a world where representations of nature often fail to match the reality – such as the popular image of the flourishing white polar bear and its starving, bedraggled real-world counterpart – the more idyllic of our images of nature do not just signify the idealised country lifestyle. They can be both a relative prestige, and a kind of unintentional escapism; they might encourage us to confront the reality a little less by providing comforting images of exactly that which is being lost.

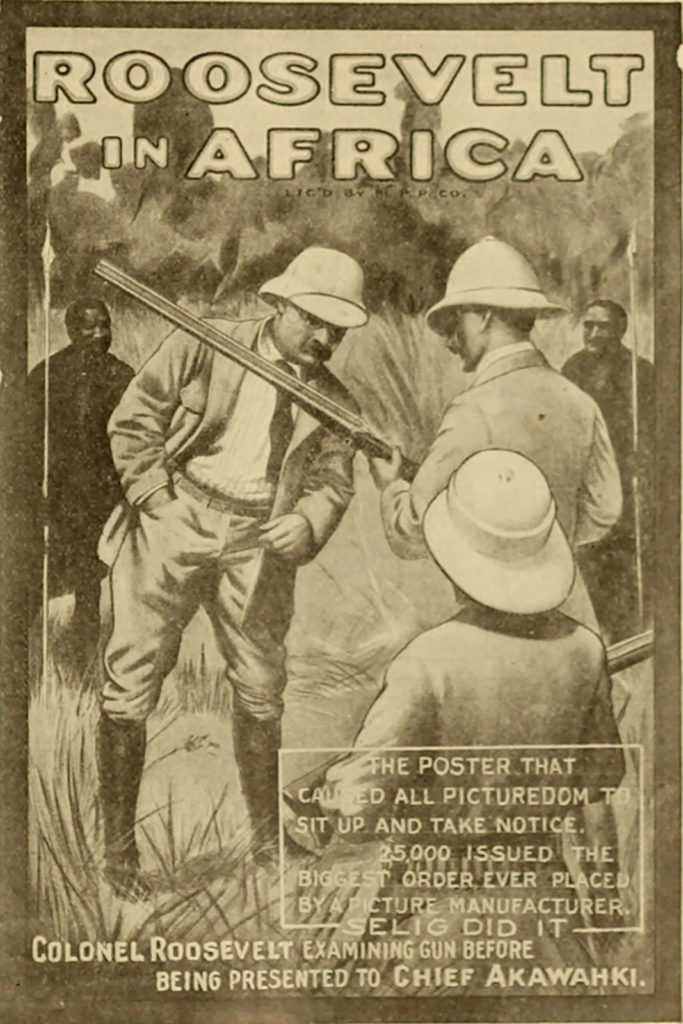

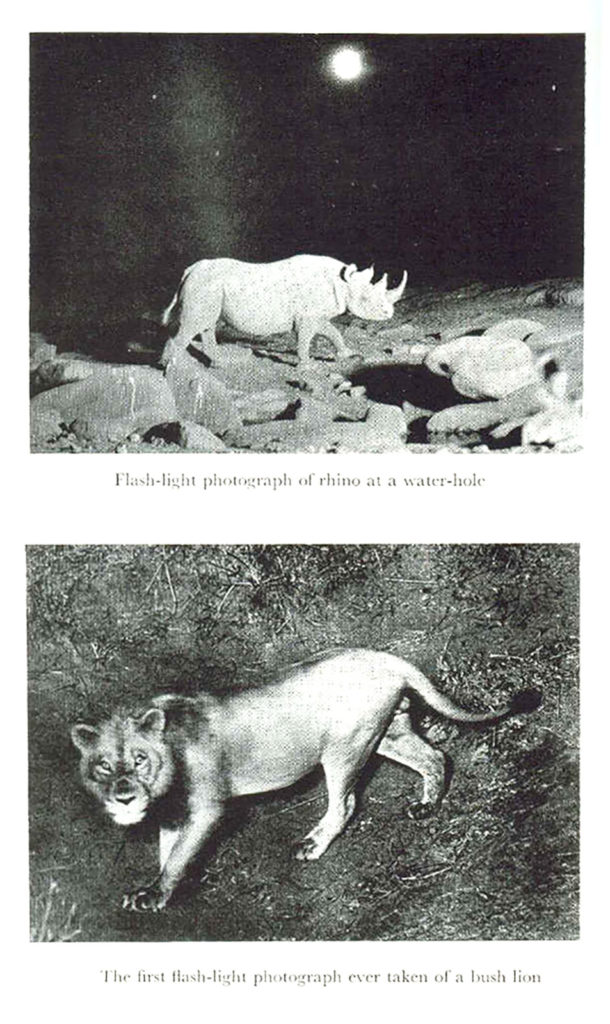

In spite of the issues we face locally due to climate change, because of our distance from the equator and the economic power that our past imperial exploits afford us even today, continents like Africa will suffer twice from the ecological consequences of first-world industrialisation and colonisation. For me, this makes the younger Cherry Kearton’s later work in Africa all the more important a reminder for us now: the fusion of all of these issues lies in Cherry’s journey to Africa with the US-American president Theodore Roosevelt in 1909. There, Kearton’s naturalist interest competed with Roosevelt’s bloodthirsty hunting campaign, which by his team’s accounts totalled over 11,000 kills including 4000 birds as well as rhinos and elephants.

“While photographic light lasted he kept constant watch, even having some of his meals brought in for fear of missing a chance. Six days spent more or less in patient waiting and watching resulted in his obtaining a series of studies, one of which is reproduced on the opposite page.” — from With Nature and a Camera by Richard & Cherry Kearton, Cassell Press 1899

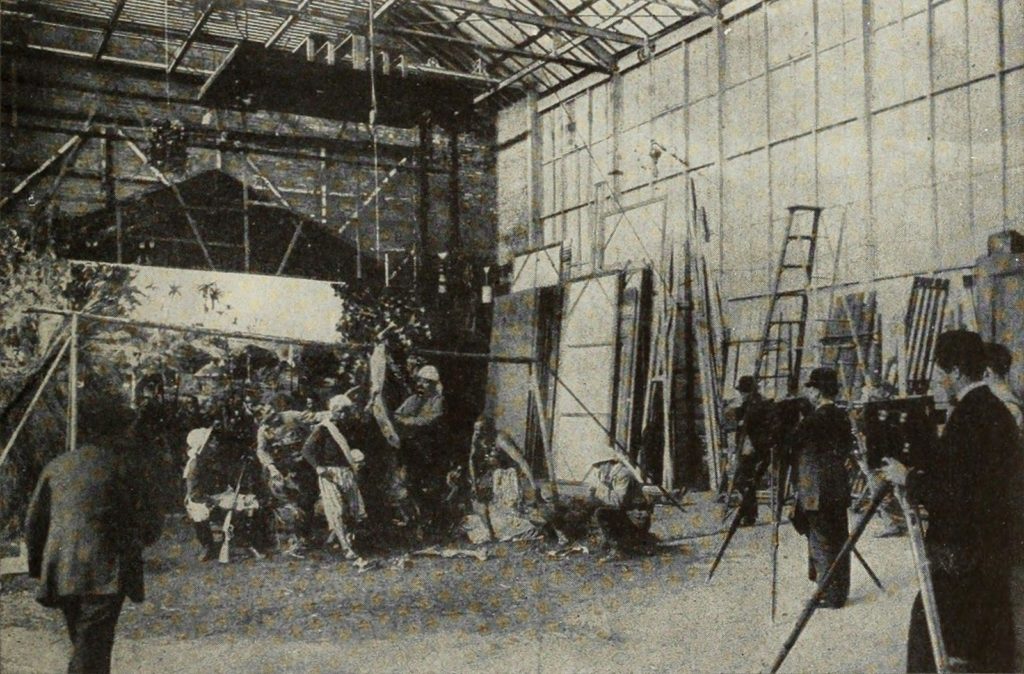

For his flaws, showmanship and tainted alliances, Cherry Kearton no doubt found Roosevelt’s behaviour repugnant, having written “remember that to help in the least degree to accomplish the extinction of anything beautiful and interesting is a crime against future generations…” five years prior to the expedition (Wild Nature’s Ways, 1904, p.210). From the start, Kearton desired to promote a kind of “camera hunt” over the more popular rifle, selling both video and stills of his time there. The public, however, expected his 1910 film Roosevelt in Africa to entertain with a spectacular massacre rather than the more contemplative, documentary-like edit he produced. So noticeable to audiences was the absence of a moving image of a lion in Cherry’s film, that a falsified recording of the trip featuring a staged lion-kill by the Selig Polyscope Company in 1909 significantly overshadowed Kearton’s efforts upon release. Even though Selig’s film and lion both were shot in Chicago, moviegoers held, much like we today, preference toward the glamorized version.

The Keartons’ indefatigable efforts, as compared with Roosevelt’s game-hunting, seem to illustrate well this dynamic, the quality of seeing cruel taxidermy “in the flesh” somehow taking precedence over the kinder mere image of life in a two-dimensional form.

A symbol of the British nation since the late Middle-Ages when the species flourished, estimations suggest that now there are just 20,000 – 30,000 lions left worldwide. The gravity of this decline has arguably been masked somewhat by the only real representations we see of such beasts: pristine, more-real-than-real and heavily edited nature photography and, to children, delightfully romantic movies like The Lion King. To modern readers, the extremes of pre-modern ecosystems seem fantastical at best; they are, as it were, unimaginable, being wholly opposite to our current situation. Yet they are more real than the romantic images of natural abundance we consume. John Mason, a Newfoundland ship captain in the 16th-century, is reported to have written that “cods are so thick by the shore that we hardly have been able to row a boat through them […] Three men going to sea in a boat, with some on shore to dress and dry them, in 30 days will commonly kill between 25 and thirty thousand“. By 2000, the fishing industry there had crashed, and now the few cod that have returned are still in the process of repopulating the region.

The causes of Africa’s wildlife decline are multifaceted, however these events represent to me an allegory of our time. On the safari, Roosevelt promoted his expansionist interests in Africa, arguing for “justice” for the indigenous people, who paradoxically, according to him, “have not governed themselves and never could”. These views, which registered as quite liberal for the time, now echo the extremist politics used to justify the West’s colonial history. Evoking both empire and wildlife, Cherry Kearton’s trip to Africa and resulting photographs are a reminder to be aware of the politics of our own time, which routinely prioritise short-term profit over long-term consequences. For those consequences, the values maintaining our current political and economic status quo are, though very different in nature, arguably no less extremist than many of the historical ideologies we regard as such now.

Original Photos by C Kearton in New Arusha lounge in Tanzania, from page 503 of the Ulyate Family Personal Communications, extract #4480, nTZ Archive (image source).

When I see the Keartons’ work, I see potential, not because I expect images like this to change our projected course alone, but because, as history, they provide both evidence of what we can learn, and, in the case of the Kearton brothers’ local efforts, an example of how we can see things. In that, I see an example of how we have the possibility to shape how we have these conversations about the future, in reference to the past. Before real change to our situation comes, we must foster a real passion for everything around us, both human and non-human, being as much a choice of our populace as it is that of the officials who govern them. The efforts of those like the Kearton brothers in Britain offers the chance to recover that acknowledgement collectively — we can change our imagination, our relationship with those more deceptive images of our world, and our priorities in saving ourselves a place in it.

I recall British nature writer Robert Macfarlane remarking during a public lecture that: “We must ask ourselves the question: are we being good ancestors?”. These words are a warning, but also an opportunity.