The World Press Photo Contest was first created in 1955 by five Dutch photographers who wanted to bring global attention to their work. Six and a half decades later, it has achieved worldwide reputation, becoming one of the most coveted prizes while making direct impacts on the photojournalism industry itself. The contest now finds itself at a historic crossroad, faced with rising decolonization and social justice movements around the world, as well as calls to mitigate power imbalances between the Global North and South that have been gaining momentum within the sector in recent years.

As a leading institution in photojournalism, the World Press Photo Foundation has to mull over the ‘world’ part in its name, revising its origin and rethinking its well-established organizational structures. “The photos of the founders, seen today, don’t tell a very radical story; they show a group of middle-aged, white men, deciding whose work was important”, Joumana El Zein Khoury, the newly appointed executive director of World Press Photo Foundation, said on the organization’s official website.

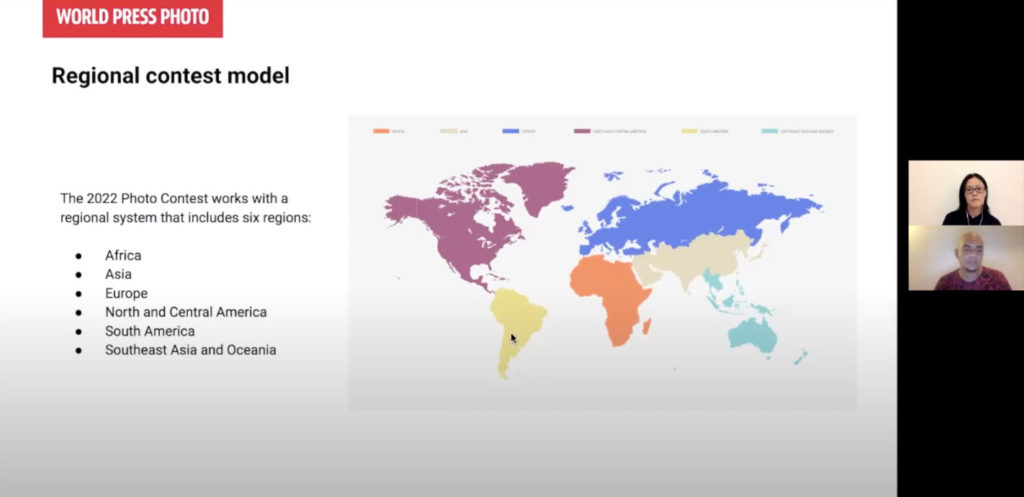

Following her statement was a slew of changes to the format and judging process of the 2022 Contest, which is accepting entries until 11 January 2022. Instead of thematic categories, entries will now be divided into four formats including Singles, Stories, Long-term Projects, and Open Format. Submitted works will first compete in their respective region – Asia, Europe, Africa, North and Central America, South America, and Southeast Asia-Oceania – before moving on to the global contest. A regional jury will also be selected based on their relevant professional expertise and knowledge of the area.

Advocacy efforts towards gender balance and geographical diversity have been set forth a long time ago. In 2003, renowned photographer and activist Shahidul Alam became the first person of color to chair the World Press Photo jury, following his complaint letter in 1993 saying “European Press Photo would be a more appropriate name for the organization”. The Pathshala South Asian Media Institute founder was addressing the narrow portrayals of his native Bangladesh in international media, one that focused on sensational images of poverty and disaster. “The emphasis on regional balance is long overdue”, he wrote about the contest’s recent changes on his personal blog.

The recent World Press Photo Exhibition 2021 held in Hanoi showcased several stories that were geographically closer to local audiences: Myanmar’s jade mining activities that carved away half of a mountain captured by Hkun Lat, the aftermath of a volcano eruption in the Philippines through the lens of Ezra Acayan, and the horrific reality of COVID-19 in Indonesia as documented by Joshua Irwandi. These Southeast Asian winners were selected by a jury with members mostly based outside Europe and North America, chaired by NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati, director of Nepal’s premier international festival Photo Kathmandu. It was “the most diverse jury” the contest ever had so far, according to Kevin WY Lee, 2021 Singaporean contest juror.

Nonetheless, the numbers remain underwhelming: Among over 4,000 photographers that entered the 2021 competition, only five percent came from the Southeast Asia-Oceania region. Africa contributed three percent, while European participants constituted half of the roster. This begs the question: Will new institutional changes help local stories earn a seat in the global conversation? The gap between expectations and reality might still persist.

During an information session about the 2022 contest at the Singapore-based Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film, Emmeline Yong, the Centre director who served as a 2020 juror in the News category, said she was ready to “turn up and be a champion of Southeast Asian works”, only to find out that there were not many entries from the region to begin with.

“A perception that many in the industry might share is that ‘we don’t see winning entries from Southeast Asia, therefore, the odds are stacked against us. Why submit?’”, she observed.

Where does this perception come from? According to Jessica Lim, director at the long-standing Angkor Photo Festival & Workshops, regional documentary photographers are caught between a rock and a hard place. With the curtailment of press freedom coupled with increasing intimidation towards those exposing criminal activity and corruption, it seems harder than ever for photojournalism to recruit new talent and retain existing ones. That is not to mention the shrinking budget for journalism and documentary works – an ongoing issue over the past years that got exacerbated by the pandemic.

As newspapers struggle financially and institutional funding for photography tapers off, photographers have no choice but to pay out of their pocket for their personal projects. But that too is out of reach for many: A needs survey conducted by Angkor Photo earlier this year revealed that a majority of freelance photographers in Asia suffered a 75% loss in income since the pandemic began. “If a media outlet won’t help them get started on a story, how on earth are they going to manage this themselves?”, Lim pointed out.

Being part of the regional jury for the 2022 World Press Photo Contest herself, she acknowledged the Foundation’s initiatives to promote inclusion and diversity while noting that changes do not happen overnight.

Meanwhile, Veejay Villafranca, Filipino photojournalist and Southeast Asia outreach coordinator for the 2022 Contest, thinks that this year offers a wonderful opportunity for regional photographers. “When you have regional judges [in the competition], we are in the room rooting for one another, we’re all there to make our voices heard.” In order for that to happen, photographers should take the first step by submitting their works, he added. As stated in the official World Press Photo website, the tectonic shifts are to help photojournalists earn their rightful representation in the winners’ circle. What they will bring remains unknown, but practitioners from the Majority World are expecting the competition to finally live up to its name this time.

*Additional writing by Ha Dao.