While exploring the UNESCO-recognized Hoi An ancient town, you may encounter Precious Heritage gallery/museum, housed in an aging building that blends in well in Hoi An’s tranquil environs. A female receptionist beams a bright smile at incoming tourists. She is but one amongst a sea of smiling women. Pictures of bright-eyed old women from ethnic minorities, shyly covering their mouths with indigo-stained hands before the Western photographer, line the walls. Réhahn’s headshots are straightforward and highly enhanced with Photoshop’s “clarity” to highlight the deep wrinkles.

The book Vietnam: Mosaics of Contrasts is filled with images of these docile, smiling women and children from remote areas, presented in a similar vein. Flipping through this collection of “portraits of Vietnam”, we see doe-eyed, dirt-covered faces. The subjects are nameless, only captioned by their ethnicities. These photographs are not taken by a casual, first-time visitor witnessing the overwhelming disparity between his appearance and theirs (read exoticness), but by a professional photographer who has made a name for himself in Vietnam and decided to call this land his new home.

And Réhahn has been successful. He has two galleries in Hoi An, one in Saigon, and one currently under construction in Hanoi. He has half a million followers on Facebook; his iconic image “Best Friend” makes headlines for being the most expensive photograph sold in Vietnam (17000$). The mainstream local media dote on a foreigner who has spent seven years exploring Vietnam’s beauty.

His popularity unsettles me. Overwhelming attention is being to work who’s subject matter and approach are trite. But what’s more concerning is the world view reinforced by Réhahn’s carefully curated portfolio.

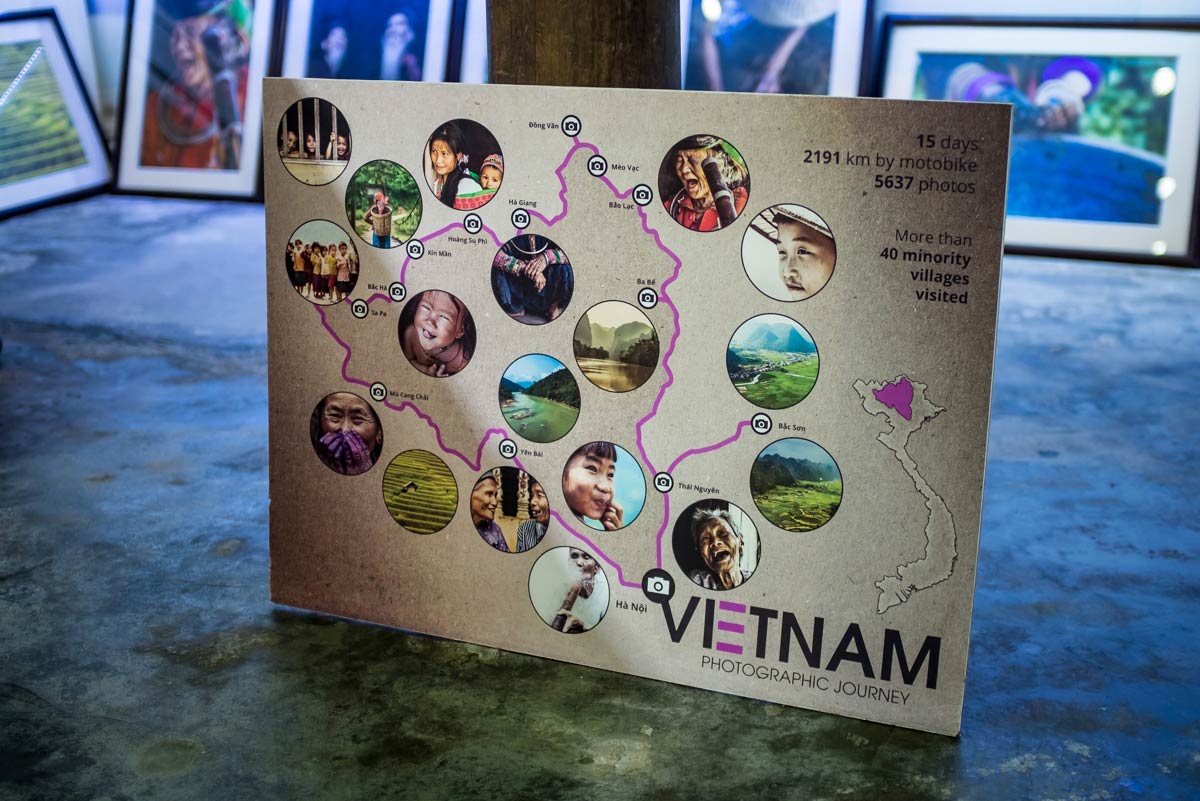

What is there to criticize in Réhahn’s vibrant and carefully composed portraits? He is not the first Western photographer to pursue projects about strange people in a faraway land. In Vietnam, romanticizing ethnic cultures has a long history, from established Vietnamese Association of Photography Artists to young road-tripping-with-a-bike travel photographers. But Réhahn’s work thrusts me into a time-warp to a Vietnam prior to when modernity knocked on our doors. What is most stereotypical of a pre-modern Vietnam has to be present. The Vietnamese wear ao dai and conical hats, the M’Nong tames elephants, the H’Mong works on terrace fields. He asked the subjects to put on their traditional costumes before taking their portraits and later expressed his regret that they are rarely worn nowadays. Flying thousands of miles from France to Vietnam, Réhahn also chooses to fly back in time to a country without motorbikes, cellphones and livelihoods other than agriculture.

Many could defend Réhahn’s style as nostalgic. Yes, it is indisputable that these scenes still exist in some parts of the country. Yet, Réhahn has chosen to photograph his subjects in pre-modern garb and postures to represent “portraits of Vietnam”. Time after time, project after project, Réhahn single-mindedly excludes the present from his viewfinder. His romanticization, persistent pursuit of “authenticity”, and portrayal of an Asian country through the lens of the past amounts to Orientalism, especially owing to his position as a white Frenchman. On the faces of old women and little kids in rural, mountainous areas with little doubt about the Western photographer’s intent, Réhahn projects his colonialist fantasy. By celebrating this fantasy, the media and public reinforce deeply-rooted stereotypes of ethnic minorities and distort the image of Vietnam, warping the country into a tranquil, timeless land of rice fields.

Réhahn is not the first photographer seeking to capture indigenous people’s portraits for fear of their cultures being swept away by the unstoppable force of modernity. His predecessors are Edward Curtis with his project about Native Americans, Steve McCurry with India and Jimmy Nelson with tribes around the world, to name a few. Just like them, Réhahn laments the imminent loss of cultures other than his own. But while these author and image makers have received more scrutiny and criticism from the portrayed communities and media critics, Réhahn’s work receives praise for its deep appreciation of Vietnamese beauty. Because more than ever Vietnam tourism industry needs postcard-appropriate pictures heavy in symbolism, and isn’t the recognition by a foreigner so life-affirming?

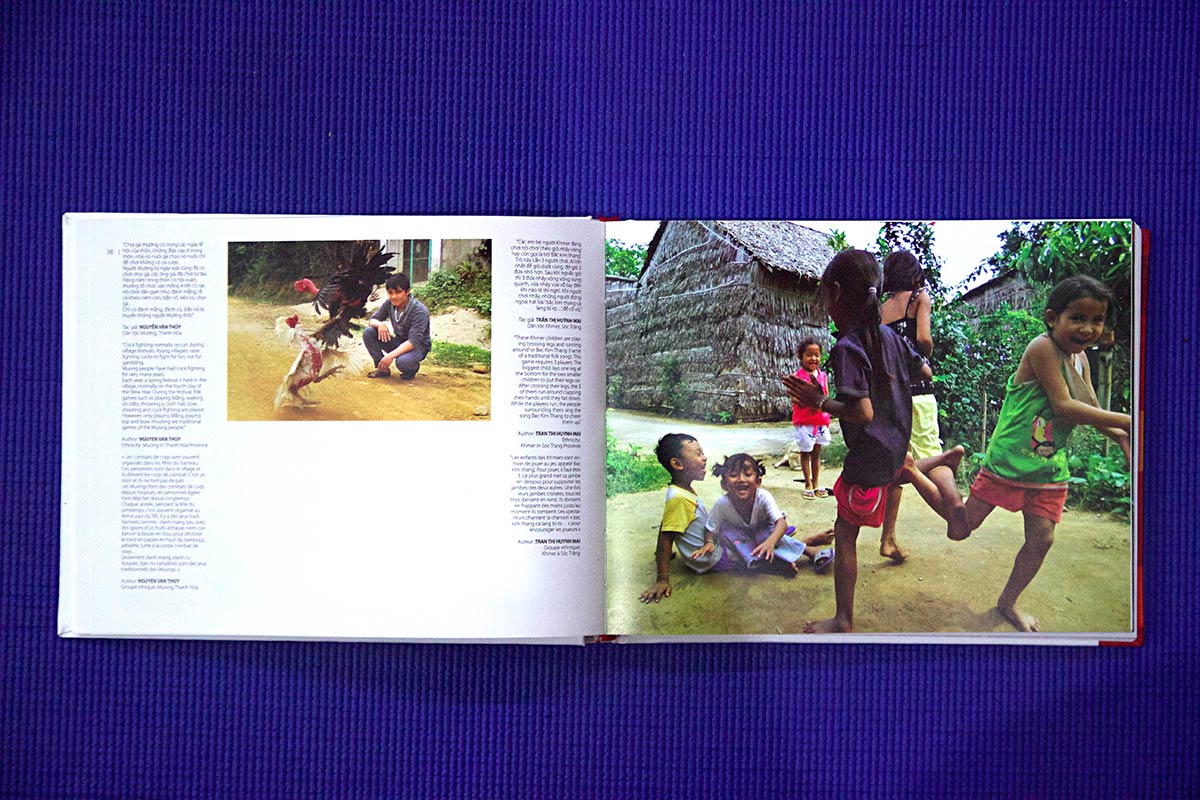

When participating in a co-authoring project with the minority community by ISEE, I came across a photobook called “My Culture” comprised of photos and stories done by ethnic minority people in a photovoice program. Taken with compact cameras by those who perhaps have used it for the very first time, these photos are visually imperfect. But, the work is generated by community insiders, casually with no particular agenda: they are of daily, working life – sometimes the subjects play flute, smoke from a silver pipe, take part in a bamboo dance, in both traditional costumes and modern clothing. But the most wonderful difference between these photos and Réhahn’s work is the autonomy of the people in front of the lens.

Perhaps Réhahn is truly concerned about the loss of ethnic culture. Not only does he take and sell photos, he also dedicates the second floor of his gallery to build a museum preserving traditional costumes of many peoples, a watered down version of the Museum of Ethnology. He recently brought 35 Co Tu people to perform in Hoi An, stating the belief that “the most efficient way to preserve the culture of the ethnic groups is to promote them outside their community […]”. Réhahn has also expressed the wish to bring 54 peoples of Vietnam to Hoi An’s old quarter one day. This scene sends chills down my spine. I hope that he does not. To theatricalize intangible heritage, uprooting cultural practices to another place for the sake of entertaining tourists, is no different from casting a pall over them in their birthplace. I also hope he stops asking An Phuoc, the blue-eyed girl, to stand next to her portrait so that visitors can cuddle her and take her picture. These activities further objectify ethnic minorities to a remarkable level. Réhahn also actively promotes his “Giving Back” project as a mechanism to defend his photojournalistic ethics, yet the power dynamic between a photographer and his subjects is more than monetary.

I do not doubt Réhahn’s photography skills. He is publicly-recognized and financially successful, a rarity today for an artist photographer as Réhahn describes himself. Yet, photography as a powerful tool for representation is more than the sum of its visual parts. The process goes beyond finding the perfect angle, beyond chatting with subjects and “making friends”, at which Réhahn already excels. Before pressing the shutter, all image makers bear the responsibility of considering the thin line between appreciation and exoticization, especially when working with minorities attached to discourses of backwardness, inferiority and passivity. And as viewers, we should look past the readymade beauty, anticipate where these images will circulate in the public consciousness, and ask ourselves how many pretty, archetypical images of Vietnam need to fill the pages of in-flight magazines and walls of cultural spaces.

Had Réhahn understood that culture is not a static entity, more than just costumes and festivals, his photos would perhaps have been more nuanced and thought-provoking. For now Réhahn’s Vietnam is a land of peace and happiness, ignoring conflicts between modernity and tradition. We only see likeable “hidden smiles” from non-threatening, simple people, enjoying life despite the lack of material comfort. Is this his intention or a blind spot? Whatever his purpose might be, his portraits will always speak more about their author than the people in them.