Nick Ut is busy these days. After 51 years working for AP, he has been travelling around the world, following invitations to teach at workshops or speak at seminars. These invitations also lead him to Vietnam – his dear country of birth, where Nick Ut is received like a celebrity. He often appears in group photos with proud colleagues or young photography enthusiasts.

Nick’s The Napalm Girl is one of the most iconic pictures of the 20th century. Taken in 1972, it transported an ugly part of the war taking place in the far away Vietnam to the American living room. It was also one of the extraordinary cases in which a war photo could actually bring about social changes. His picture simultaneously received several prestigious accolades, including the Pulitzer prize, and also set a firm foundation for Nick’s budding career in photojournalism. Then, he was only 21 years old with no prior experience before admitted to work in AP.

For half a century, Nick Ut and The Napalm Girl have been relentlessly praised by the media. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the photographer and his work have been elevated to the status of a “legend”. But by simply listening to his talk or meeting him in person, one could easily reckon the discrepancy between his unadorned stories and the hyperbole attached to his name.

On the one hand, its wide influence on the media and popular culture deserve all the credits. After appearing on the cover of The New York Times, it has stirred the anti-war sentiment and quickly become an icon raised by peace-loving American citizens in protests. Thanks to its historical significance, Nick Ut receives the status of one of the most influential photographers, even after the war has ended for 40 years. It was also the last war that he covered.

On the other hand, such discourses based on pathos have distanced the audience from the photographer’s original intention. Elevating a photographer or his work could mean conjuring a sense of admiration. But sometimes, admiration is not a beneficial emotion. It builds a wall between the audience and the real issue the photograph wants to communicate. In other words, it makes them look up to the photograph instead of going around and viewing it from different angles.

Let us all be reminded that photojournalism, regardless of its grand purposes, should be regarded as a profession first and foremost. In both wartime and peacetime, following and capturing events is a job that photojournalists are hired to do. As a matter of fact, a photojournalist does a good job by taking pictures following the direction pointed by the editorial office.

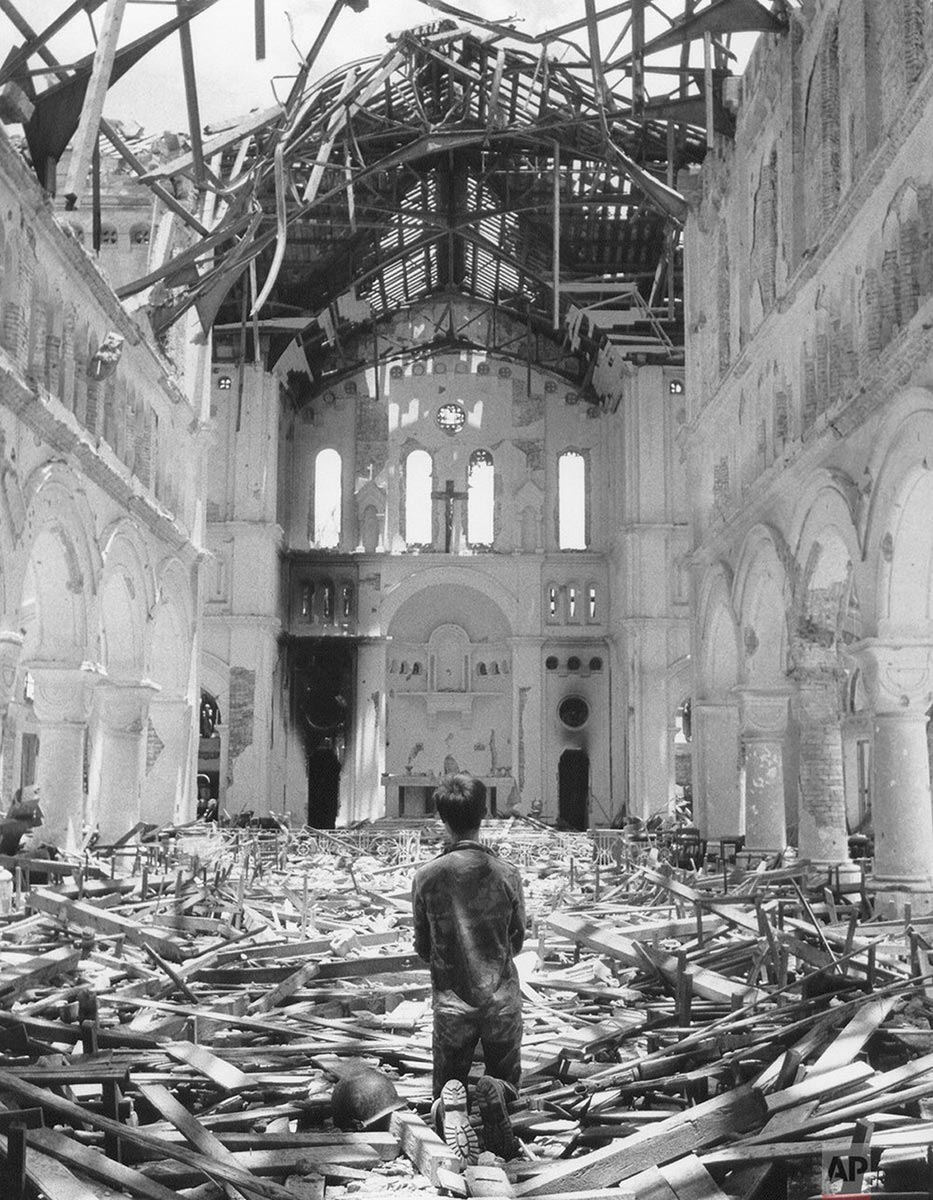

During the Vietnam War, the AP bureau in Saigon employed many veteran photojournalists including Horst Faas, Larry Burrows, Malcolm Browne and Eddie Adams. Pictures that speak about the meaningless suffering of the war taken by this group of devoted photographers (including The Napalm Girl) were put together in a book titled Vietnam: The Real War published in 2013. In this collection, images of civilians stuck in an endless circle of violence abound. AP’s commitment to bearing witness to inhumane crimes has brought them 6 Pulitzer prizes for their war coverage. But the price was dear. Many of their photojournalists were killed on the field, including Huynh Thanh My – Nick Ut’s big brother.

Back to The Napalm Girl, the bombing in Trang Bang in 1972 is obviously not the deadliest in the war that stretched more than 20 years. Rather than directly showing bloody killing, the photo captured the moment when a group of children narrowly escaped death. In the center, Kim Phuc, a 9-year-old girl was crying out loud in her naked and gaunt body as the Napalm jelly burnt her skin.

Horst Faas’ decision to publish the photo was not without opposition. Until then, there had never been images of naked children released by AP, nor by any agency for that matter. Growing up, Kim Phuc admitted hating seeing her naked image everywhere, not to mention the troubles it caused in her personal life. But both Horst Faas at that time and Kim Phuc later on understood that the image had to be out timely. Probably thanks to its never-seen-before provocativeness, it has awakened American citizens that were kept in the dark. And despite not being in control, the subject Kim Phuc eventually agreed to compromise her privacy to let the anti-war message widely spread.

Nick Ut has done a good job as a photojournalist, which is to be in the hotspot to capture pictures for the agency he works at. He often referred to The Napalm Girl as “the picture that stopped the war”, fulfilling the wish of his late brother who used to be an AP staff photographer. But as a matter of fact, the image alone could not hasten the war’s end. It was the accumulated effect of the editor’s timely decision, the consent of the subject, together with previous coverage that put pressure on the authority and the course of the war in 1972. That specific context played a major role in the ferocious public reaction to the photo.

Let’s consider another hypothesis. If The Napalm Girl were to be distributed widely on the Internet nowadays when straightforward pictures of violence are the norm, would it have similar influences? When the public is so used to seeing photos of atrocity and pain to the point of desensitization, a counter-reaction is not out of the question. The photographer could be thought to attempt to build a name for himself on others’ pain, or that the innocent girl is suddenly forced to be a tool for propaganda.

Image is an effective tool to invoke empathy and change public awareness. After all, direct images of violence arguably cause the strongest mass reaction. Yet the relationship between war photos and their audience is nowhere near simple. Shocking images either attract attention to rightful issues or exploit characters and glorify misery. In a time of image saturation and continued violence, visual literacy and critical thinking have become of utmost importance. Such skills can only be gained once we stop putting the photographer on the pedestal while turning a blind eye to the ecosystem where their works float.