If not already a plain truth, Ho Chi Minh City’s rapid economic growth for the last ten years is evident in its three-fold GDP increase, according to the data provided by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam. But it requires no statistician to figure out this fact: high-rise buildings racing to sprout one after another aren’t a sight easily missed. Photography is fast in capturing the result and reproducing it, populating the Internet with a plethora of images featuring the city’s skyline overlooking the Saigon River. Sometimes they are interjected by photos of the Notre Dame Cathedral or the City Hall against the backdrop of some soaring towers, hinting at a colonial past that still plays an indispensable part in the city’s identity. A prima facie conception of HCMC follows – an emerging postcolonial metropolis with high hopes of competing with regional and international rivals on the economic ground.

This impression is not one without flaws and inadequacies. Grand imageries of newly built megastructures, no matter how eye-catching, are bound to gloss over certain past and present controversies surrounding the city’s urban development. It could also downplay any social, environmental, and political problems that threaten the appeal of an economically thriving front. Moreover, a city never appears the same to two dwellers, for the multitude of private experiences defies a singular characterization.

Interestingly, insofar as photography can be abused to rehash the same potentially problematic imagery, it is also a potent corrective apparatus to spotlight unheeded issues, highlight suppressed voices, and express the residents’ subjective lived experiences. This perhaps has to do with the capacity of the medium to expose naked truths when capturing the reality as seen and felt by the photographer, and the relative accessibility of the craft.

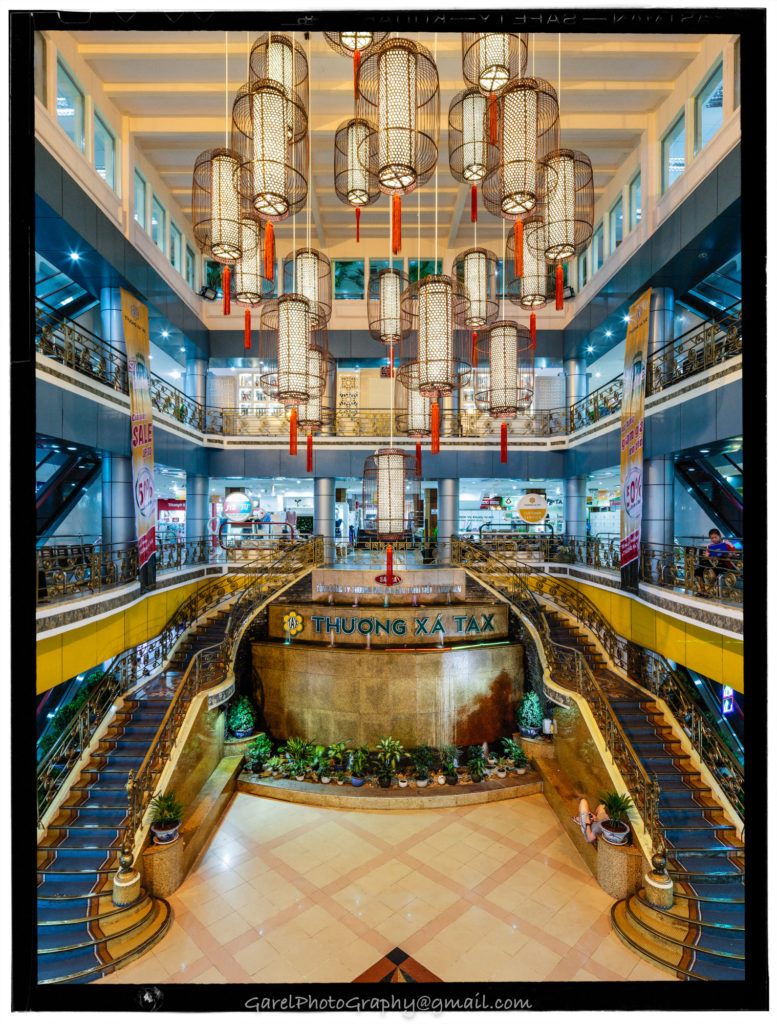

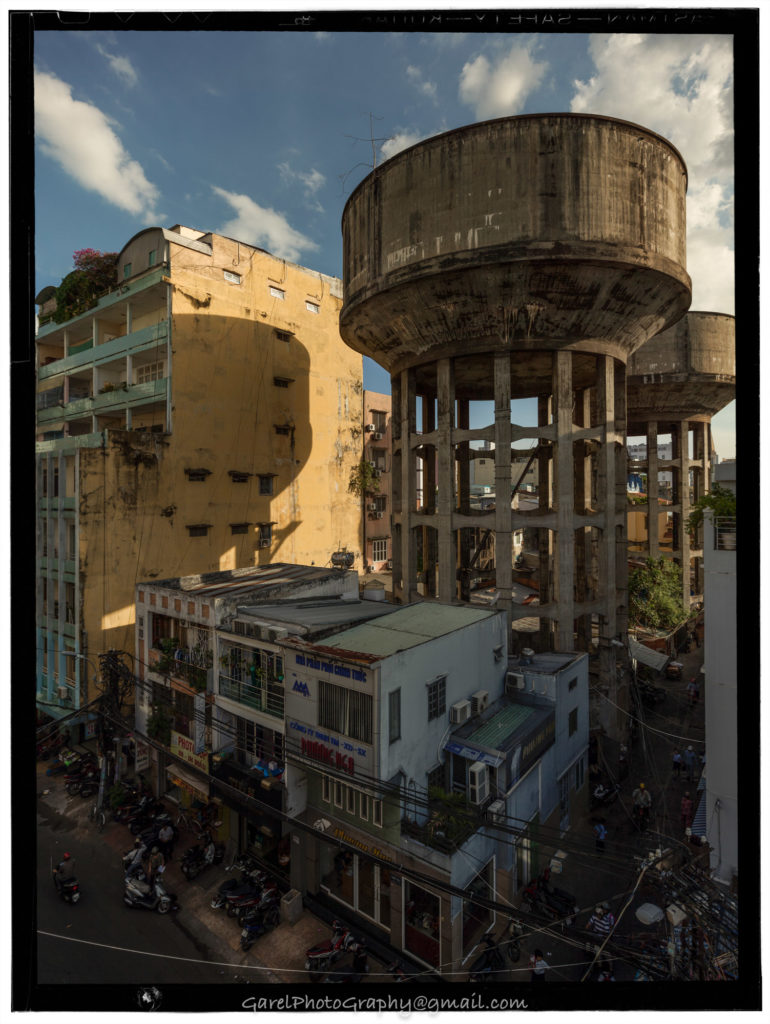

The most apparent use of photography in this regard concerns urban renewal – the tear-down of old buildings to make space for new construction. A possible response would be to document structures that might vanish in times to come, an implicit mission taken on by Alexandre Garel, a French photographer based in HCMC. “It is not fear, it’s reality,” stated Garel matter-of-factly, when asked if his efforts to photograph Vietnam’s modernist and vernacular architecture stems from the fear of losing sights of these distinctive architectural expressions. Guided by a formal fascination with the built environment of the country, his photographs carry with them not only the photographer’s sense of nostalgia, but also his attitude of dissidence with the ill-handling of the city’s urban development.

Certainly one might find it problematic for a French man to make aesthetic claims about the postcolonial built environment, for urban renewal can also be read as a means to decolonization (1). But as the city reinvents itself with the generic, ahistorical, and decontextualized forms, one can’t help but wonder if the rush for foreign investment and middle-class expenditure has robbed the city of a unique identity and the situatedness in time and space.

At the same time, it is imperative to not over-romanticize the city’s modernist and vernacular architecture. Admittedly, the quaint sights of old residential houses or public buildings erected from the last century have a profound appeal to humans’ sentimentality. Observers can be quick to assign and fixate meanings to the veneer of these built forms, but inhabitants can have a totally different mind. Wouter Vanhees’ The Alley project explores this line of thought. His series of photographs juxtaposes old, lowly-built houses in an alley against a daunting background of high-rise condominiums. At first glance, they seem to convey an imminent encroachment of modern high-rises upon vernacular houses, vilifying the homogenizing process of modernization for upending individual idiosyncrasies.

However, certain ambiguities can be gleaned on closer examination. In one photo, a lady is captured in her courtyard behind a makeshift fence, gazing upon a looming high-rise at the back. With her back facing the camera, it’s not clear if the act is coming from fear of losing her house to real estate giants, or if it’s filled with a desire to afford a high-rise apartment as such, or something in between that the character is trying to make sense of herself.

The regular, identical-looking facade of the high-rises might also belie any individual idiosyncrasy hidden behind the closed doors and windows. The openness of old, lowly-built neighborhoods often enables private affairs and idiosyncrasies to spill into the public realm and be captured on photographs, to the inhabitants’ happiness or not. But the lack of access to the internal space of condominiums needs not imply the negative. If so, “the towers’ physical structure is nothing more than a thin layer of superficial modernity designed to fuel dreams and aspirations,” commented Vanhees in our exchange.

That would be a very good reason to shift the focus away from architectural forms to the happenings and activities of the inhabitants living in the city. Such is the approach taken by Cuong Tran, evident in the profuse body of works featuring his observations of fascinating stories around where he lives and works. In documenting the myriad of city dwellers’ different ways of life, his works represent the many colors that paint Saigon’s vibrancy, a quality defined not by prebuilt spaces but what inhabitants make of them.

Sometimes, several social undertones are embedded in his observations. In capturing the less materialistic way of life in the suburbs, Cuong also portrays the disparity between the development of the city’s downtown and its rural counterparts. Environmental concerns are another aspect of his works, posing questions about the tradeoff between the city’s rapid pace of urbanization and its livability.

In documenting the myriad of city dwellers’ different ways of life, his works represent the many colors that paint Saigon’s vibrancy, a quality defined not by prebuilt spaces but what inhabitants make of them.

Perhaps with all the problems plaguing modern life, many city dwellers actively seek an alternative experience that doesn’t require traveling outside the city. This inclination is captured in Nhut Minh’s works that showcase the tranquility of the city’s rarely seen scenes. The characters appear in serene contact with nature, too absorbed in their getaway to have a second thought about what they might miss in the urban district located right across the river.

These photos are the result of Minh’s chance encounters during his own respites from the hustle of urban life. In these mini adventures, tranquil scenes are few among his many other fascinations with what the non-urban can offer. “Wandering to places away from the city helps me release pent-up emotions, and find new inspirations as well”, he shared. The rather peculiar sights of kids playing around concrete pipes or buffalos doused in an eerie shade of cyan are testament to a wealth of imageries knowable only outside the purview of the urban realm. Indeed, the built environment both expands and restricts the scope of one’s lived experience; but precisely in a city undergoing perpetual urbanization does the interface between the urban and non-urban come about, generating riveting compositions that imply the inhabitants’ attitude towards this duality and transformation.

It is worth noting that photographs need not be a direct translation of the world. Rather, they can be an expression of the photographer’s own truth, as in the case of Dat Vu. His occasional photos taken in Ho Chi Minh City often feature an everyday object in close-up and arguably allude to certain human behaviors unique to the inhabitants specifically living in a particular area, or not. One photo shows a piece of cloth laying flat on the street, probably blown off from the median strip where other laundry is hung. In a not too far-fetched reading, one can make several inferences about the circumstances that configure this image: maybe the people who hang laundry here are from the lower middle class, relying on wit to utilize readily accessible public structures in place of a drying rack.

But Dat laughed at that line of interpretation. “It’s not to understand; it’s to feel,” was his response. With modernity comes the championing of rationality, and Dat couldn’t care less. His body of work is thus less about featuring an reality external to the photographer, and more about presenting to the world what reality looks like through his own subjective, idiosyncratic lens. “Photography is autobiographical for me. It documents where I have gone to and what I have done, and creates a past that I want to keep and to have.” As the city ceaselessly grows and transforms, his fear is not about losing the urban forms, but the memories born out of them.

Interestingly, the more we go inwards into the mind of the photographer, it’s not true that the city plays less significant a role. We witness this in Lien Pham’s series Return, a collection of works that expound on the relationships with her family members in the urban realm, especially within the confines of the domestic space. Conceived during her trip back to Saigon with the aim to make sense of and to heal from impending emotional turbulence, the photographs unfold soft but stifling tensions between family members caught in uncanny sights. The story is for sure particularistic, yet nebulous: it’s not entirely clear what gave rise to this family dynamics and the permeating sorrow.

My exchange with Lien reveals a bit more about her process. All the scenes, despite being staged, are recreations of what she has previously seen of her family members, and of what they have told her about, which she might not have witnessed firsthand. For one, the reenactment enables Lien to put the way she perceives her family in the material form of photography. But more than that, it gives her an opportunity to embody the missed moments of the family members, be it in their private rooms in the house or other spaces to which they frequent for their daily activities, using the visual language of a medium capable of simulating reality. In the process, she reconnects with both her family and the city that she has lived far away from.

Through Lien’s and Dat’s photographs, we get glimpses of their world, or in Dat’s words, “dreams”. These little visual narratives are unique and specific, often not fully comprehensible, even more so when patched together in an amalgam. But that’s totally the point, for they reject a reductionist understanding of the city in terms of economics and grand architectural gestures. What we get instead is a kaleidoscope of Saigon, or Ho Chi Minh City, or whatever name one wishes to call it, in its most faithful form.

At the end of all conversations, I asked the photographers for their opinion about the city’s prospect, given how fast it is changing. Some are prepared for a future where it is no longer recognizable, and economically, socially, or environmentally uninhabitable; they would then not hesitate to leave. Others are more optimistic. Despite certain bleak outlooks about the urban environment, Cuong commented, “From my interaction with people, I think Saigon will still sustain its generosity. Even if there are setbacks, it will still be a livable city.”

Even with an abundance of captured images, the future can only be guessed, never truly known. Photographs shall remain a keepsake for us to relive our private and shared sentiments anchored in this too endearing city to truly part ways, even if only in dreams.

(1) Selective erasure of colonial history via urban renewal is an aspect of Singapore’s post-independence urbanization, which Rem Koolhaas, a Dutch architect and architectural theorist, describes as “30 years of tabula rasa”.