MATCAxC4 JOURNAL: Conversations Around Photography, Vietnam & UK

A series of articles discussing various aspects of image-making. Supported by British Council Vietnam’s Digital Arts Showcasing grant 2021.

????✍️??

One of the biggest photography collectives in the UK is now so well-established it’s easy to forget its radical roots. But Magnum Photos, which was founded in Paris in 1947 and opened its London office soon afterwards, was one of the first photography collectives in the world. Owned entirely by its members, and allowing the photographers to retain the copyright to their own work, Magnum set up an empowering situation that allowed it to explore sometimes controversial issues. That’s true to this day, and Magnum also now runs its own spaces, including a print room in its London offices, and a large new office, exhibition space, viewing room, and library that recently opened in Paris.

Magnum is now part of the photography establishment, but its example can be seen streaking through the UK photography scene; like Magnum, some of these collectives and independent spaces have lasted so long they’ve become institutions. Take the Amber Collective. Formed in Newcastle, in the North of England, in 1968, Amber had radical intentions and covered marginalised communities dispossessed by the political and cultural mainstream. It also pooled its members’ resources. Founder member Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen is still active in the Newcastle area.

Amber opened its exhibition space, Side Gallery, in 1977 and, recognising kindred spirits, Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson opted to have a retrospective there to celebrate his 70th birthday. Amber and the Side Gallery are still going strong and still highlighting marginalised lives – Side’s current exhibition is a solo show devoted to Indian transmedia artist and activist Poulomi Basu, which uses images, film, and VR to engage with issues of gender, caste and class in South Asia.

The 1970s were a radical time in the UK, in which activists and artists were rethinking existing narratives and power structures, and many other British organisations and galleries have their roots in this time. That’s particularly true of photography-focused galleries, because at the time photography wasn’t widely accepted in museums and art institutions, particularly if it had a documentary focus. The Four Corners film and photography centre was set up in a squatted building in 1973 by its four founding members, for example; nearby The Half Moon Workshop [later Camerawork] and gallery was setting up in another squatted building, creating engaged photography and a ground-breaking magazine, Camerawork. Camerawork closed in 2000, but Four Corners is still going and it maintains the archives of both organisations.

Edinburgh’s Stills Gallery was founded in 1977 by the Scottish Photography Group; meanwhile, London’s Photofusion Photography Centre was established as a co-operative in 1979, and Glasgow’s Street Level Photoworks was set up in 1989 by a collective. Autograph ABP, London’s influential organisation and space for photography exploring issues of race, identity, human rights, and social justice, was originally set up as the Association of Black Photographers in 1988 by a group of photographers including Sunil Gupta, Ingrid Pollard, and Rotimi Fani-Kayode.

Even The Photographers’ Gallery, now one of the bastions of UK photography, was originally set up as an independent space, albeit not by a collective. Founder Sue Davies mortgaged her own home to create it in 1971, frustrated by the lack of institutional support for photography; the first exhibition was The Concerned Photographer, a social documentary show curated by Cornell Capa, brother of Robert. It included images by the Magnum co-founder, and by early Magnum member Werner Bischof.

But physical space remains important, and photographers are continuing to find ways to set up alternative galleries.

And if the UK photography scene has a rich history of collectives and independent spaces, it’s a history that’s still in the making. Photography is now firmly established within museums and galleries, but image-makers, particularly those with shared special interests, are still gathering together, and still opening spaces to show work outside the mainstream.

Document Scotland is a collective of three photographers set up in 2012, for example, which aims “to witness, and photograph the important and diverse stories within Scotland at one of the most important times in our nation’s history.” MASS Collective has a similar concept but (so far) applied to London. MASS Collective’s first project, Londons, brought together eight photographers to document the UK capital’s built environment, for example, driven by the idea that this very large, old, and multicultural city is best tackled from a number of perspectives.

MASS got together during Covid but still managed to pull off an impressive group exhibition at The Building Centre in 2021, an organisation and space dedicated to architecture; MASS also put together an equally impressive zine. The group is now planning a wider project looking at Britain’s industrial heritage, as well as teaching workshops and leading photography tours. The Revolv Collective, which was set up in 2017, has a similar approach, also based on the desire to work collectively, and also leading several education initiatives.

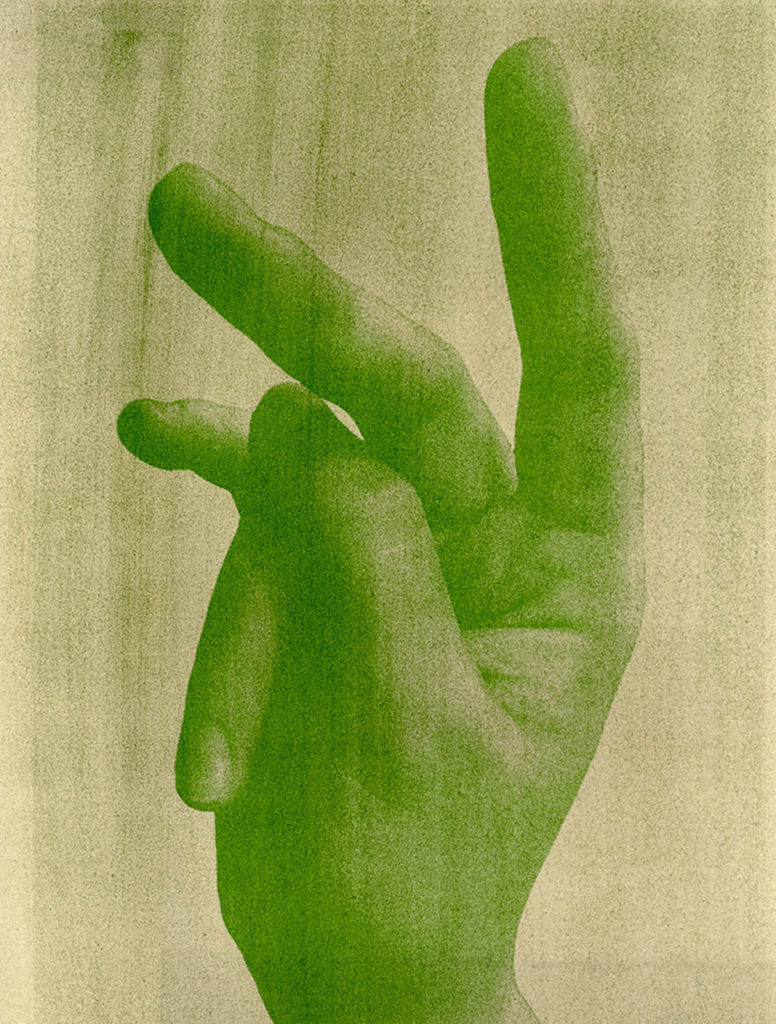

The London Alternative Photography Collective was formed in 2013 with a slightly different motivation, as a platform for image-makers interested in unusual photographic processes. At the time there was little information about what these processes were or could be, says co-director Almudena Romero, so the group became a valuable network for sharing skills and knowledge. Last year Romero won the prestigious BMW residency for her project The Pigment Change, which sees her printing using the chlorophyll in plants; this prize came with exhibitions in 2021 at two of photography’s biggest events, Les Rencontres d’Arles and Paris Photo.

The RAKE collective was also underpinned by a desire to share skills, with the founder members bringing together various specialisms in photography, coding, research and activism. Using these skills to investigate issues such as police surveillance and the spread of far-right ideology, RAKE was one of the recipients of The Photographers’ Gallery 2021 New Talent Awards. RAKE has also set up the RAKE Community, an online forum in which other participants, interested in similar areas, can share skills and collaborate.

In fact, the internet is proving an interesting arena for special interest groups within British photography. Firecracker, founded in 2011 by Fiona Rogers, is a forum for promoting women in photography through online features, networking opportunities, and public events, for example. In-Public was set up in 2000 by Nick Turpin as a collective of international street photographers; Turpin left in 2018, but not before In-Public had proved its mettle by arguing for the right to take photographs in public in the face of restrictive laws around terrorism and privacy.

… while few would argue that private galleries are independent exactly, some have recently been behaving in ways that feel quasi-institutional.

But physical space remains important, and photographers are continuing to find ways to set up alternative galleries. Ronan Mckenzie set up Home in London at the tail end of 2020, for example, a creative space which she feels addresses the ongoing lack of support for non-white artists. It is, she states “one of very few black-owned art spaces within London, and one of the only to be artist led, with a leading focus on supporting Black and Indigenous People of Colour”. Interestingly Home isn’t supported with public funding, and received support from the Gucci fashion house for one of its recent shows.

The question of public funding puts an interesting spin on independence though, because while few would argue that private galleries are independent exactly, some have recently been behaving in ways that feel quasi-institutional. The Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol has been set up by the Magnum photographer himself, for example, but runs a busy programme of free and low-cost exhibitions and events, as well as maintaining an impressive photography archive. It’s a private initiative, but it feels worlds away from a print sales-focussed private gallery.

London’s Richard Saltoun Gallery, meanwhile, which shows lens-based art alongside other mediums, has run two year-long exhibition series in the last couple of years, one around feminist art, the other around Hannah Arendt’s writing. Similarly, Seen Fifteen, also in London, has just started an entire year of programming around The Troubles Generation in Northern Ireland – a programme which isn’t focussed on print sales, instead supported by an arts organisation, The Genesis Foundation.

Seen Fifteen’s director Vivienne Gamble is also an instrumental part of Peckham 24, an annual not-for-profit festival of photography which runs alongside the Photo London art fair. Emphasising the emerging, the experimental, and the edgy, Peckham 24 doesn’t rely on sales and doesn’t receive public funding either; instead it’s supported by private financing from various individuals and organisations, pulled in by Gamble and her co-founder, the artist Jo Dennis.

Offshoot Gallery, also based in London, is a ‘community interest company’:, a limited company, but one that exists to benefit the community rather than private shareholders. Like Seen Fifteen and Richard Saltoun Gallery, Offshoot Gallery runs long-term curatorial projects, inviting two guest-curators every year “to realise exhibitions that challenge current social and cultural themes”.

And on a final note, it’s worth considering the independent educational organisations in UK photography, which range from workshops to entire schools, such as the Work Show Grow programme organised by artist Natasha Caruana. Alejandro Acin’s IC Visual Lab has been an independent photography hub in Bristol since 2013, making publications and running exhibitions, collaborative workshops, and, recently, a year-long mentorship titled Elective Affinities, which matched six local and international artists with peers. Acin started IC Visual Lab to fill a gap in Bristol’s institutional cultural offering; things have moved on in the city now, he says, but being independent still offers advantages such as being able to take risks and experiment.

The exhibition for Elective Affinities, which was part of the Bristol Photo Festival programme, took place in a disused post office in a busy shopping mall in the city centre. “I like the idea of ‘interrupting quotidianity’,” Acin explains. “Using unconventional spaces to display work is a very powerful act of resistance but also it offers another opportunity to those curious minds that may not fancy going to a museum or an art gallery, but have a great sensitivity about the world.”

All Rights Reserved: Text © Diane Smyth; Images © all noted parties; Autograph installation photographs © Zoë Maxwell; Header © Martin Seeds/Seen Fifteen