The world seems to be the award-winning photographer Souvid Datta’s oysters until the first online outrage over his photo of an underaged sex worker seemingly being raped broke out. Naturally, scrutiny followed the whole series documenting a red-light district in Kolkata, India. When a photoshopped image resurfaced, the online presence of Datta went up in smoke: from a hefty profile on main photography sites, the results now revolve around his ‘transgression’ and ‘misconduct’.

To sum up, critics were blaming Datta and at the same time showing sympathy for him as a ‘victim’ of today’s system. As the whole photojournalism industry questions itself after the incident, I as a photographer am bugged by a perpetual issue of how to be a good photographer in today’s context, while producing good photographs is only one job among others.

Shocking images – a real demand.

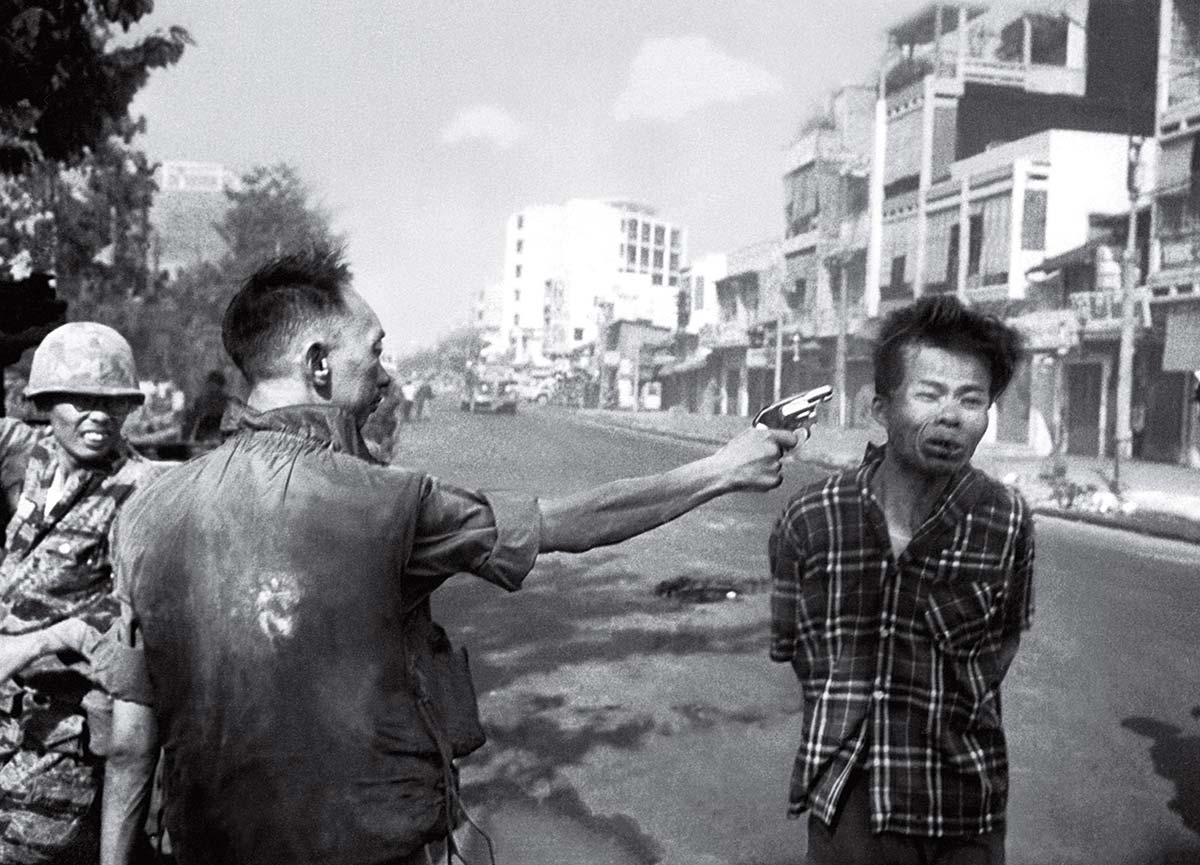

Photography has long been linked to the human condition. For a short history of a century, it has become an important element in documenting and providing visual comprehension of atrocities in the world. Thus, despite numerous articles lamenting how the contemporary photo industry is going downhill by constantly demanding photographs with shock value, I beg to differ. Since the birth of photojournalism, raw and provoking images have always been favored by media. Many controversial decisions have been tested and tried until a “code of ethics” is drafted. Nick Ut with Nalpam Girl, Eddie Adams with Saigon Execution or Kevin Carter with Starving Child and Vulture are all prime examples of photojournalism showing extreme violence or poverty with intention to provoke extreme emotions from viewers.

To me, traditional photojournalism as we know perhaps still remains the same. Nothing major has changed in the way it functions. It was built up by photographers, editors and audiences who believe in the necessity of explicit images. They have managed to make known a different reality, evoke benevolence, teach us compassion and indirectly contribute to policy change in some cases.

When this photograph by Souvid Datta showing a 16-year-old sex worker sexually assaulted by a man was used as a promotional material for LensCulture’s competition, a great number of people were infuriated at how the minor subject’s face was fully revealed. Yet almost the same image, created by Mary Ellen Mark 39 years ago, was received with a more understanding attitude from the audiences. I researched deeper into each of these images and speculate that people might not be angered by what they see but rather by what they understand from these images. If you put the project of Souvid and Mary Ellen Mark next to each other, despite their uncanny visual similarity, the approach and how the story is told (representation of his/her subjects) are contrasting. On one hand, there is Mary Ellen Mark who spent 10 years in getting to know and becoming a sister to those she documented despite countless failed attempts and initial hostility from them. On the other hand, Souvid Datta actively investigated the issue of human trafficking and provided too much information, which accidentally stripped dignity off his subjects. Yet it is only my speculation that MEM’s picture might suffer similar backlash as Souvid if Falkland Road was published today.

The same thing can be said for Nick Ut with Nalpam Girl. Despite showing full frontal nudity of a child, the image was published and gathered strong reaction from peace-loving American citizens, putting pressure on the government to end the Vietnam war that had already caused too many casualties. Yet the one by Kevin Carter, another iconic image taken with intention to reveal to the Western world a harsh reality they have never seen, was met with opposition, resulting in the artist’s tragic decision. This leads me to think that the more widely an image of suffering circulates, the more likely its photographer’s actions in such situation is called into question. While Nick carried the child to the closest hospital and did everything he could to make sure she got treated properly, Kevin had to make a difficult decision of not intervening and helping the child.

The final outcome of a photographer’s job is indeed their photos. However, increasing attention is being given to what they have done before and after taking such photos, especially if they are of people and place of suffering. Does being a ‘good’ photojournalist justify the ‘photojournalistic distance’? After all, we as viewers were not under that particular circumstance and pressure so it’s rather foolhardy to judge. Yet when living in an increasingly visual world as image makers and viewers, I believe we need to question our own, sometimes subconscious, tendency to quickly consume news through explicit images.

The desire to be known.

Photographers have always been judged by how many awards they have won, publications they have had and how well they are being connected. Like any other creative occupation, photography has never been only about how good you are at photographing. After a recent case of image manipulation and plagiarism by Souvid Datta, many critics are blaming the photo industry for creating a system that is repetitive in content and low in level of visual literacy. I have mixed feelings about this.

On one hand, I think communities like LensCulture are the best things happened to documentary photography in modern day. They are a great source of inspiration and active in educating visual knowledge for photographers. Without communities like that, we would not be able to see so many amazing works of emerging photographers, learn about social issues around the world and participate in ongoing discussions of the practice.

At the same time, I find it hard not to agree with what critics are saying. Awards and grants set a specific standards, leaving little room for experiment. Many photographers consequently produce similar works that please these standards, in order to get exposure and support. Photography is as much a form of personal expression as it is a reporting medium, so it is problematic when these standards are thought to be absolute guidelines of storytelling methods: some go as far as heavily manipulating their images to get the standardized aesthetic. Yet experimenting in photography is imperative. Especially, in a time when everyone has a camera and the best images already set the bar for what should be photographed, it requires us to find alternative ways of storytelling to create a personal stamp and retain the dignity of our subjects.

Despite an ocean of indistinguishable works on human exploitation, there are still some that manage to cut through the clutter. The works by Nina Berman and Cristina De Middle are two cases which instead of putting the spotlight on victims of abuse, they turn their lens toward the majorly disregarded subjects – the perpetrators. Both the projects explore the mind of perpetrators through portraits and photographs of evidences used to convict abusers. Through unconventional approaches, the photographers are able to tell the stories without furthering the stigma of those who have already suffered immensely.

A couple of years ago, I also did a photo essay on underage prostitution in Hanoi and brought it to a few portfolio reviews for feedback. And most of the feedback I received were “Why did you choose to hide her face?” and “You will need more images of her and the customer in action to illustrate the story better for our audiences.” Because of that, I did question my method and practice, whether they are inadequate or not. And I am still asking myself the same question everyday. Choosing between traditional storytelling of using explicit images or unconventional approaches with a more subtle way to divulge the issue will always remain a dilemma for any working photographer. Sometimes the most impactful decision might be the one that risks harming your subjects. The ability to balance between the harms and benefits proves more necessary than ever in telling stories of others.

Deep in my heart, there is always a special place for traditional practice of documentary and photojournalism. There are still many photojournalists who are working hard out there, living by long-established guidelines. Therefore, instead of claiming that traditional photojournalism is dead just because a few mistakes made, we should have been asking ourselves why we still expect documentary and photojournalism to function based on traditional values and ethics when our social context, human interactions and technology have evolved drastically.

Nowadays the concept of ‘truth’ is being challenged even more often. A huge volume of information can be easily looked up with few simple clicks. After all we as photographers have little power besides establishing relationships and sharing a reality or an idea. In trying to understand others and treating them with utmost respect, we in the process learnt a lot about ourselves. That’s perhaps one of the most beautiful things about photography. Hence, as a photographer, the best we can do is perhaps making sure we represent our subjects with the dignity they deserve and illustrating the story as close to our heart as possible.

During one of my class with Fred Ritchin, he said two quotes that I think perhaps the most suitable to end this article. “A good photograph is an imitation of another good photograph” and “Everyone publishes images of atrocities but they don’t show us why these atrocities happen”.

Mai Nguyen-Anh is a Vietnamese visual artist who has great concern in contemporary issues, now based in Hanoi. In 2016, he finished One Year Certificate at International Center of Photography in New York.

Follow him on Facebook and Instagram.