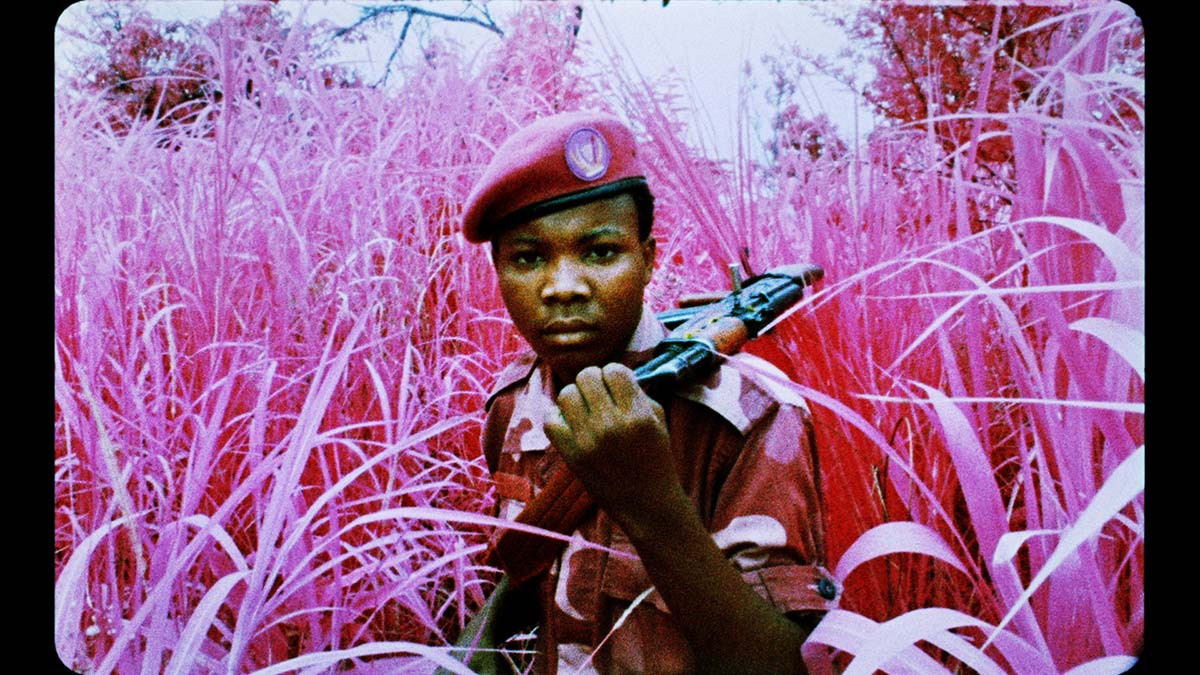

A young man sternly fixates on the camera lens, his eyes confrontational, his lips tight, his right hand covering the barrel of an assault rifle hanging loosely on his shoulder. He wears a beret and a military uniform in camouflage pattern, but without badge. In another picture, vast swathes of plateau spread unto the horizon, as a small, lusty stream runs sinuously in the middle of it. Both photos are expressively pulsed in a palette of fuchsia, which triggers immediate, reactive, hallucinatory optical reception. The luscious pink-red shades that replace earthy colors in the footage are the results of an infrared, false-color reversal film originally used by the American military to detect camouflage in thick undergrowth. The Enclave, a video installation by Richard Mosse* teleports the viewers to the heart of a civil war that leaves traces in the mesmerizing landscape of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

“How do you cover a war that involves at least twenty different rebel groups and the armies of nine countries, yet does not seem to have a clear cause of objective?” asked Jason Stearns, who worked for the United Nations in Congo. Mosse arrived in the DRC with little background knowledge on the complexity of the region, in addition to his formal preconceptions of the Congo from Joseph Conrad and Roger Casement. For a largely overlooked conflict that has endured since 1998 and resulted in more than 5.4 million war-related deaths, he had no intentions to reduce it into a simple story.

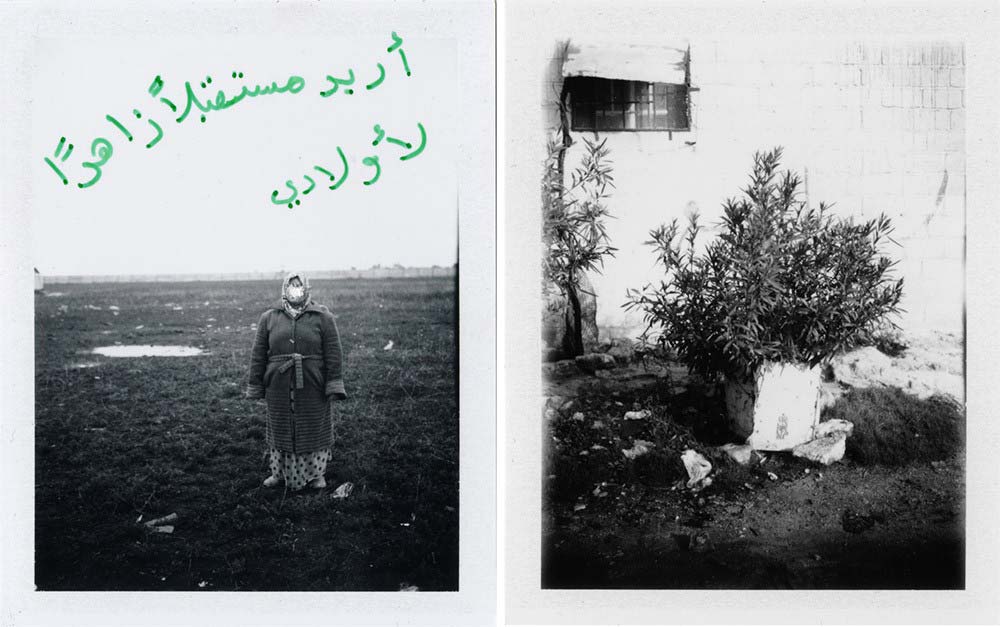

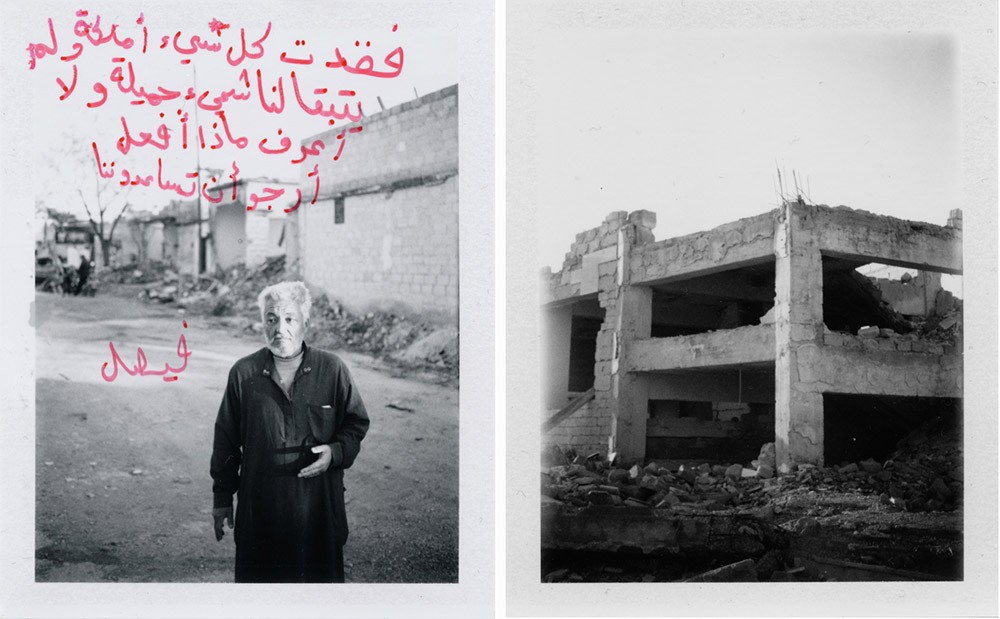

Considering another less well known photo project from a less well known photographer / artist, Syria and its inhabitants can be seen in black and white polaroids and colorful highlighters. Turkish photographer Cihad Caner arrived in Aleppo and Azaz in December 2012 with a polaroid camera to embark on a series titled Remaining. He took photos of a few Syrians whom he met, then asked them to draw something on the photograph he had just taken or to respond to his questions: “How do you feel? What do you expect from this revolution? What do you think about your future?” In some of his photographs, a 24-year-old man shares that he’s afraid of death, a middle-aged woman scratched her face from the polaroid for fear that she would be recognized by the authority, a brother and a sister show their neighborhood with walls full of bullet holes, a silver-haired old man collapses at the prospect of nowhere to return and with no one to turn to. In the beginning, no Turkish magazines accepted to publish Cihad’s project, citing that it was too artistic. Remaining however later went on to win the first prize at the Photographic Museum of Humanity’s photo contest.

Both projects trespass the elements of timeliness and objectivity that are considered to be essential in conflict photojournalism. But both photographers also deliberately attempted to do so to make us reconsider what we thought we have known about the act of documenting wars.

Early photojournalism was in fact, born out of a necessity to document armed conflicts. It was the foundations of Life magazine in 1936 and Magnum photos in 1947 that moulded an enduring visual style of photo-reportage, setting what was, and still is, considered exemplary photojournalism. The past few decades have however, seen a dramatic transformation of traditional photojournalism, made able by the dizzying technological and digital advances, into a globalized hit-and-send business. Photographs are no longer bounded by time and space, easily made accessible to a global audience. The photograph is seen as more effective and reliable than words due to their memorability and directness, and as a commonly-shared visual lingua franca that seems to require little background understanding and interpretation.

But the Internet has a double-edged influence on the dissemination of the images of war. Ultimately, the photograph, once “a means of making ‘real’ (or ‘more real’) matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore”, as seen by Susan Sontag, has suddenly become displaced, overexposed, its effects desaturated, its implications devalued. Unlike words, photographs are often received without much scrutiny and fact-based inspection. But the risk of exposing to a mind-boggling number of online images on a daily basis is that it potentially turns us into passive voyeurs of deaths, sufferings and their vertigo. We retreat from the horror, the monstrosity, the disaster, once the viewing session is over, and we slip back to our daily life, preoccupied with other nearer, other humanly distractions. We are far from the DRC, Syria, Palestine, South Sudan and more. The war photograph grows into just another illustration of a savage war somewhere.

As we scroll back to the images of the US-Vietnam war, we remember the time when the predominant visual narratives were looked from the other side of the frontline. We also remember the time when images bear witness to an American atrocity against Vietnamese women and children, when a picture of a young girl screaming and running naked towards the camera during a napalm attack captures the cruelty of the war and when the scene of a public execution fuels resentments against the futility of the fighting. The visual message might be direct––take Saigon Execution by Eddie Adams for instance, but it does not necessarily guarantee a full disclosure of what is behind the act of killing. The text, the caption, the layout, the framing and more, all constitute in the making of a selected meaning from many possible ones out of the image, but which might as well serve a particular agenda. What we see is not all there is.

In this age of mass consumption of information, how do we cultivate a culture of critically reading images? Perhaps it’s more like a question of contextualization, of locating images within the social historical dynamics, or simply, the act of making questions itself. When we look at Mosse’s footage of the DRC, few questions might ring: Who are the rebels in the image? (Mosse claimed he followed several groups of rebels) Who are they fighting against? What are they fighting for? The same goes with Cihad’s Remaining series, as we are unable to draw any background information related to the war in Syria, except for very intimate moments of ordinary Syrians caught in the crossfire sharing their pains and hopes for the future.

Even when there is much to reconsider when we look at Richard Mosse’s war reportage of the DRC––whether such devastation and sufferings should be beautified and idealized, how he positioned himself as a white, male artist working in a wartorn, postcolonial country, how he purportedly selected his subjects of portrayal and more, it should be emphasized that by opting for an unconventional approach to capture a humanitarian crisis, he was able to secure a necessary degree of attention to a highly contested yet under-reported war. Following the screening of Incoming, his new film about migration crisis, questions regarding politics and aesthetics surfaced again. “Aestheticising human suffering is always perceived as tasteless or crass or morally wrong”, Mosse says, “but my take on it is that the power of aesthetics to communicate should be taken advantage of rather than suppressed.” Conflict of interests remains a concurrent issue in photojournalism, even when after all, the goal of anyone working in this field would be to make long-lasting impact rather than a faltering impression that vanishes after a few clicks.

A recent exhibition at the Center for Art on Migration Politics in Copenhagen titled “We shout and shout but no one listen: Art from conflict zones”, confronts audience of today’s visual communication with an indispensible question: what does it mean to truly open one eyes’ to the images of conflict?

This is a response from reader Bao Yen to our previous article Should Suffering Be Romanticized?. Bao Yen is a journalist based in Hanoi, Vietnam.

*Check out Richard Mosse page from Artsy for more of his works, exclusive articles, and up-to-date Mosse exhibition listings.