When I introduce anyone to Sebastiao Salgado and James Nachtwey’s works, they would without fail be compelled by these symbolistic images representing a part of modern history. The attraction comes not only from their information about ruined landscapes, austere faces and heart-wrenching expressions, but also their aesthetic qualities: a frame of a woman kneeling on her beloved’s grave or terrified looks on a refugee family’s face are miraculous moment of lights – their composition as perfect as that of a master’ painting or a climax scene on a theatrical stage.

After two wars spanning over the 20th century, images of Vietnam have been historically shaped by photographs of the war damage by international news agencies. These are scarred memories of our history, but they have served as valuable documentation that has helped change the world’s collective opinion about the nature of war, and more importantly, transformed the definition of contemporary photojournalism. Only two decades later after the reunification and improved living standards did the art of photography find its way into Vietnamese people’s lives, then we started asking ourselves: Should photographs about catastrophes look beautiful? In the following analysis, I will share my personal view on works by Sebastiao Salgado and James Nachtwey, two great monuments of contemporary photojournalism, and present an alternative approach to record humans’ not-so-beautiful realities.

Salgado and Nachtwey have borne witness to many world conflicts: the bigger the calamity, the heftier artists’ ambitions. I reckon an irony in their career which has lasted for more than half a century in dangerous regions: it’s that they have gathered fame and glory from forgotten lives. The irony is pushed further through the dramatic and almost romanticized ways in which these sufferings are depicted.

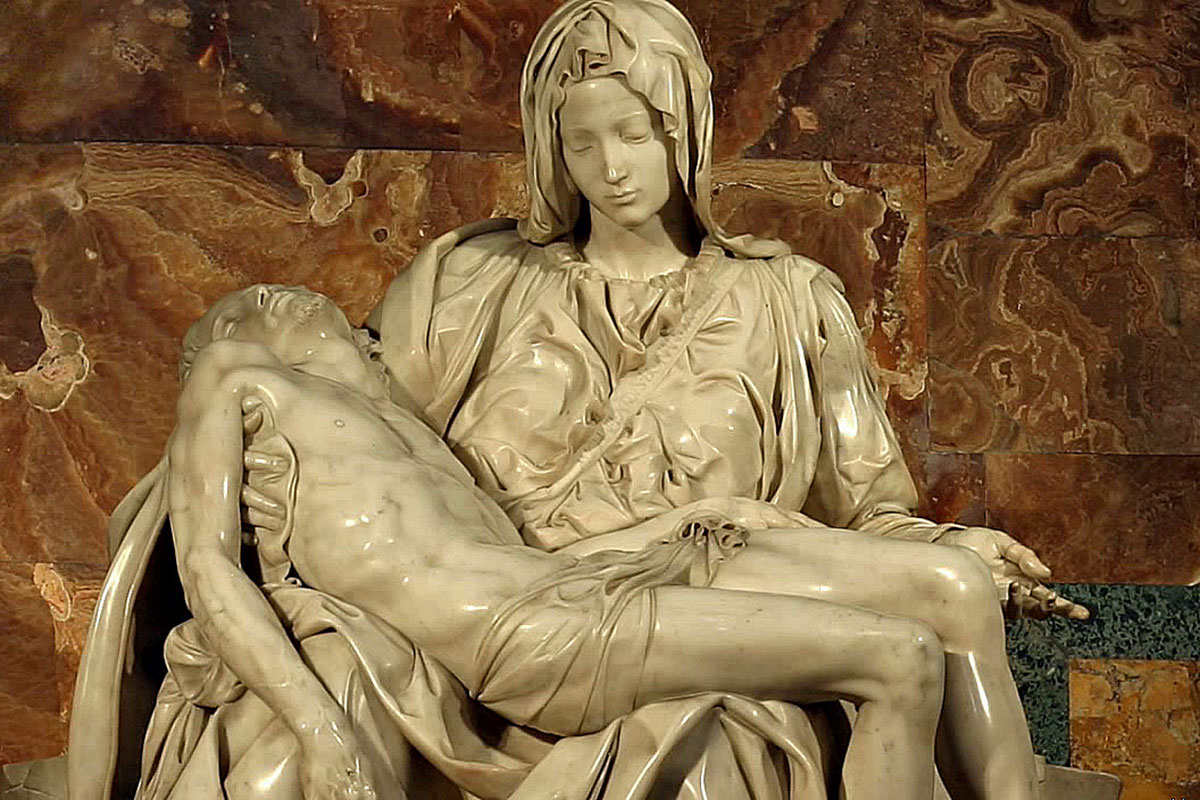

2000 years of Christian art was built on the foundation of the beauty in tragedy, and it is not difficult to recognize the influence it has on Salgado or Nachtwey. Yet, the subjects in picture are not characters from the Bible but people with their own life and identity. When suffering is depicted in paintings or sculptures, these works often have the same visual and aesthetic quality as that of a photograph, but their content and character are radically different. In paintings, the events and people are rooted in myths and legends while in photographs there is palpable death and pain. I have been wondering, is chasing beauty and perfection in a frame appropriate when the subject is a suffering victim of a catastrophe?

Nobody could dismiss their sacrifices as well as the values that Salgado and Nachtwey’s works have created. Danger to their own life, psychological trauma, losing friends in battles – these are the loss they accept to document turmoil, to guide the world’s attention to conflicts calling for resolution. Those who support Salgado and Nachtwey would argue that a beautiful picture is easier to capture attention and even give dignity to unfortunate people. But when presented with a heavy load of pictures of people’s faces contorted by misery, I find it impossible to evade the question of whether the characters have been exploited.

In 1993, at Salgado’s exhibition at the International Center of Photography, controversies around how to approach and communicate human tragedy again started to surface. Is there any other way to depict these misfortunes, besides taking raw photos of violence and pain to evoke sympathy?

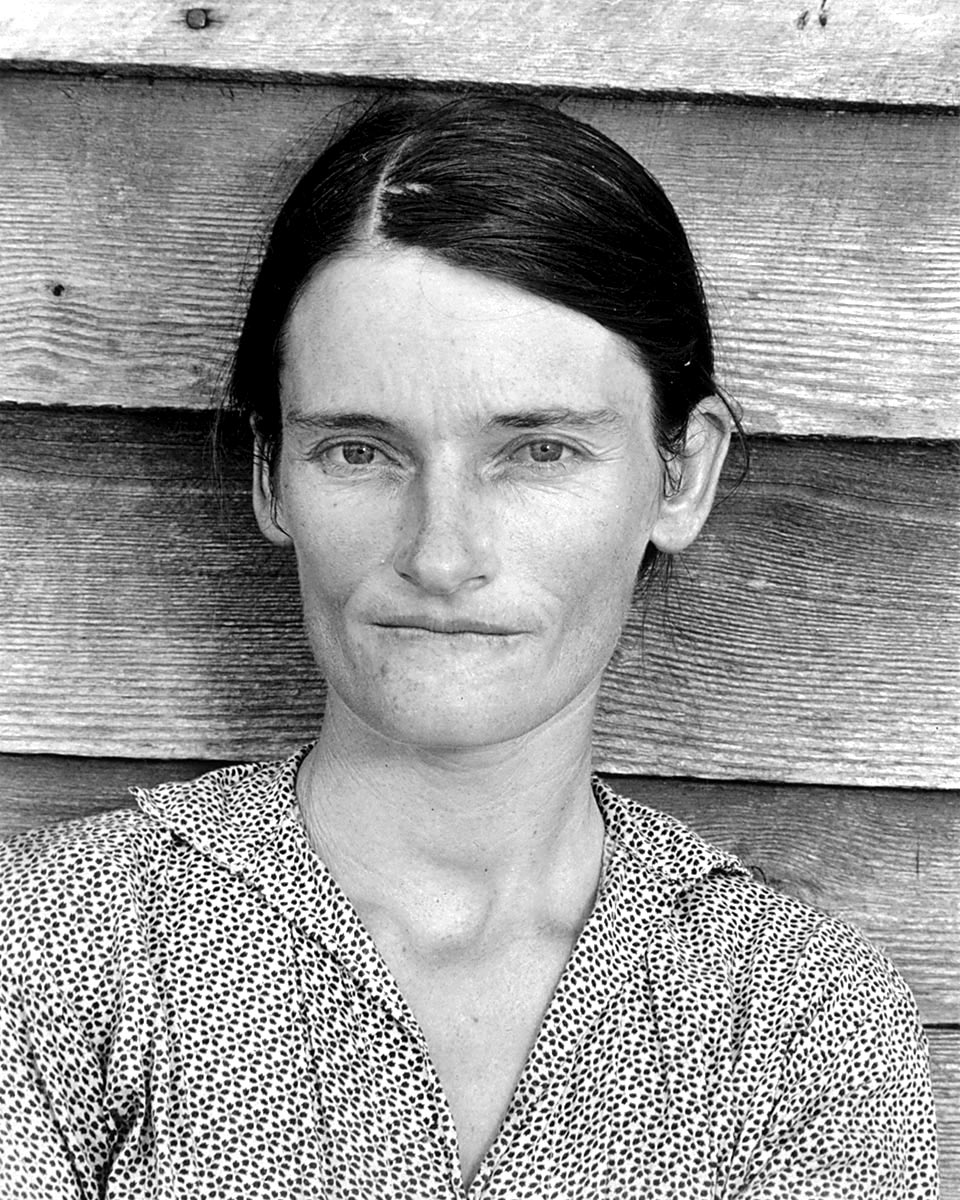

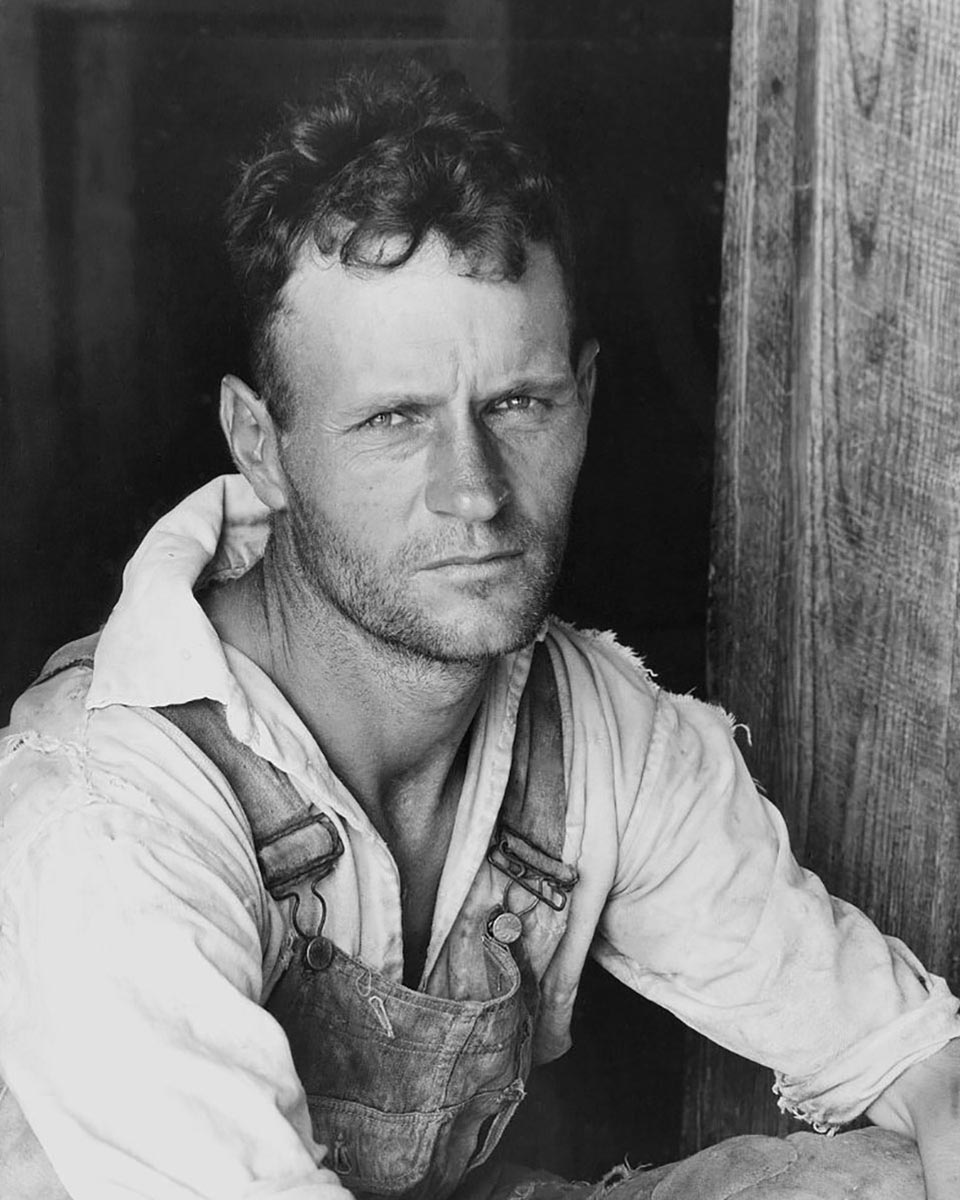

At the time, critic Ingrid Sischy from the New Yorker compared Salgado with Walker Evans in a long article. She stated that works by Salgado could not touch the audience the way Evans’ did because of the didactic, almost cruel imposition and the tendency to symbolize people and events. In contrast, Evans’ portraits which are deemed to be representations of The Great Depression contained a sense of humour and sarcasm and were more familiar to most viewers. According to critic Lionel Trilling, most photographed people in these eye-level shots looked straight at the photographer / audience, their faces exuding a sense disbelief and resistance, as if refusing to be an object of ‘social consciousness’. Evans’ photographs are stark examples of ambiguity in art, which allows viewers the space to derive their own meanings. This suggestiveness is also one of the brilliant attributes of arts.

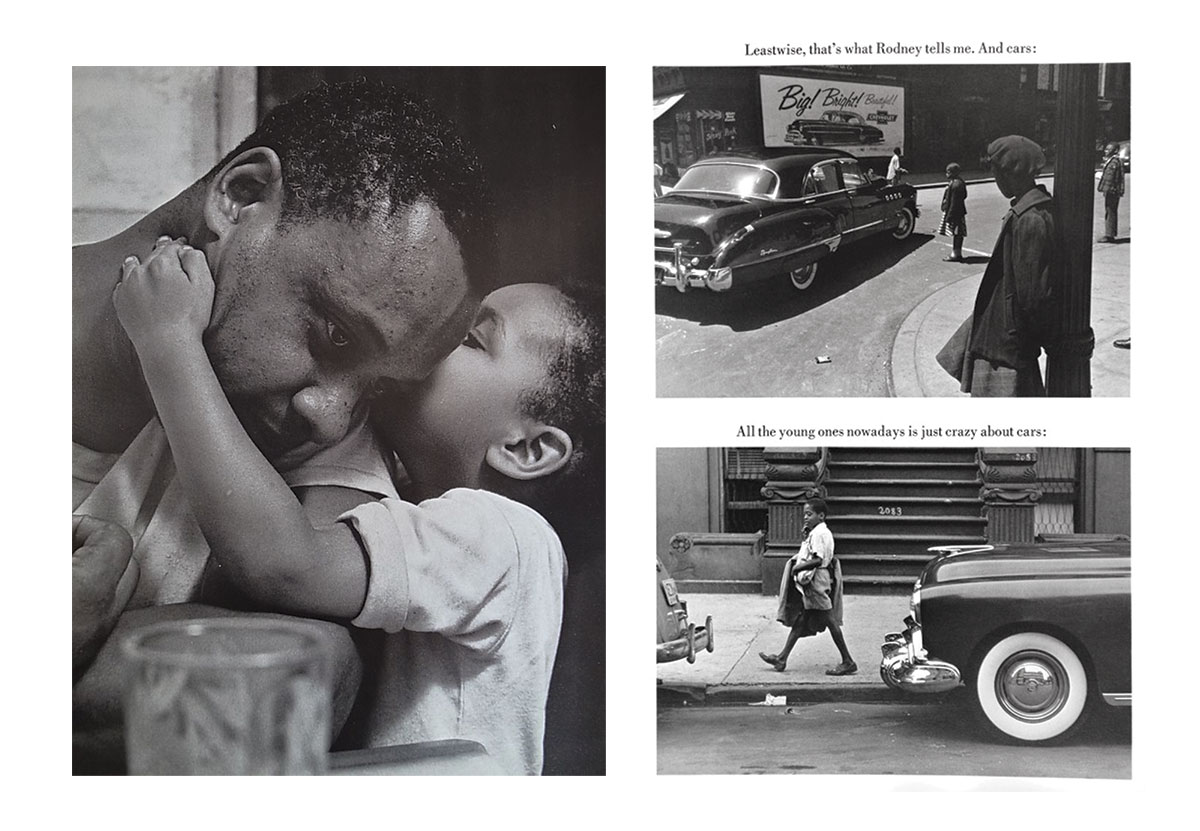

While Nachtwey and Salgado made works for the sake of reportage and propaganda and Evans kept a neutral ground in his photographs, Roy DeCarava chose to tell his story with his heart. Being a black artist himself, he actively worked during the height of civil rights protests led by Martin Luther King Jr. However, DeCarava did not shoot photographs to reveal discrimination or police brutality towards people of color despite them being a constant reality. Instead, he sought the most intimate, most humane moments of people his community. The photographs showed us how black people love and dream just like anyone, and deserve equal treatment in the US or anywhere else in the world. Not looking for foreign lands or intense battlefields, DeCarava wandered but around New York, where he was born and raised to shoot his friends and acquaintances. He ended up producing photos of genuine intimacy and understanding that no outsider not familiar with the struggle of his subjects could ever take.

In spite of the differences in approaches and intentions, all images above by Sebastiao Salgado, James Nachtwey, Walker Evans and Roy DeCarava are brilliant works of art and historical evidence. They played a vital part in helping people understand and have compassion for one another by showing them other realities. In other words, each work serves the purpose of a social study that enables humans to acquire a greater understanding of humans.

I find it hard to conceive why James Nachtwey maintains the same mode of narration at the age of 70. I ask myself, is the artist being carried away with their heroic vision of bearing witness to crimes against humanity, so much that the notion of photographed individuals as people with a life outside of this tragedy slipped their mind? Once Salgado shared that he was haunted by his own images to the extent that he had to take a break at the peak of his career to find some peace of mind. Yet currently both Nachtwey and Salgado are still making works chasing the same ideal, so I suppose they have found a resolution to their inner torments.

In the end, many generations of Vietnamese photographers and even I myself regard Salgado and Nachtwey as lasting monuments of contemporary photojournalism. They have inspired a great number of photographers to take photos that are not just visually beautiful but can create an impact on society. “Should suffering be romanticized?” is an important question especially for young photojournalists to which I hope everyone can find their own answers. For my part, I think artists like Walker Evans and Roy DeCarava have solved the conflict between tragedy and beauty.

Mai Nguyen-Anh is a Vietnamese visual artist who has great concern in contemporary issues, now based in Hanoi. In 2016, he finished One Year Certificate at International Center of Photography in New York.

Follow him on Facebook and Instagram.