As chosen participants of the Reciprocal Artist Residency With Objectifs x Matca 2019, two artists Lac Hoang (Vietnam) and Kian Wee (Singapore) have spent 4 weeks in the neighboring country making new work. While Lac Hoang focuses on foreign domestic workers and their relationship with public spaces in Singapore, Kian Wee is fascinated by the mysterious Hoan Kiem Turtle as a specific example of myth-making mechanisms in modern society.

In this duo interview, they will share their work in progress and discuss insights about the residency program.

First of all, can you share why you decided to apply for this residency program?

Lac Hoang (L): I saw the open call on Matca and thought that it would be a good opportunity to spend one month on a project. Given that it’s not a long period of time, it is still substantial to break away from the daily routine that doesn’t always count towards an art practice, and have the mental and physical space to focus on something. It’s also a good chance to live in a new country, meet different people and see what artists in the region are working on.

Kian Wee (K): Previously, I did a one-year group residency at The Substation, one of Singapore’s oldest independent art spaces. So it is a natural progression for me to venture out of my comfort zone, as well as try a different medium or technique.

Is your understanding of the proposed subject based on online research different from what you actually encounter in Hanoi/ Singapore?

L: I started my project with the proposed idea of working with foreign domestic workers (FDW) in Singapore. Looking up keywords online, I found most results in the media focusing on FDW as a group vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

After the first week arriving in Singapore and contacting actual subjects and some organizations working with FDW, I realized that it’s only a small part of the problem. Rather than using my project as part of human rights work, I am doing this from an outsider’s perspective who is trying to learn about the matter. I can’t change anything, so might as well do something more personal and have direct connections with people.

K: There wasn’t a lot I could find in English about the Hoan Kiem Turtle online. The small glimpse I had is that it’s a sacred legend adored by the people, and I did meet many who totally feel that way. On the other hand, my project deals with how cultural beliefs are formed in a country that is constantly developing, and the sense of detachment the young generation has towards such myths. I had that suspicion and interviews with people here reaffirmed that. Like Thao, I took a personal approach towards the subject because I came here as a foreigner and the turtle itself is still an icon, no matter what people may or may not believe.

While having a background in photography, both of you have taken the residency as an opportunity to experiment with other mediums. Why did you decide to do so?

K: Through an imagined perspective of the iconic Hoan Kiem Turtle, the work-in-progress aims to reflect my views on the relationship between the now deceased turtle and Hanoi residents. At the start of my research, I asked myself: How do I talk about something that is already gone? How does one express the absence of something which still exists in some other form? It was from these questions that made me want to experiment with moving image and animation. It actually isn’t that far off from my photography workflow; I still have to think about the story and how to tell it through images, whether still or moving.

L: As my research on the topic evolved before the departure date, I was re-considering this choice of medium; as the subject matters are quite sensitive and I wasn’t sure if photography is democratic enough as an approach. I eventually switched to doing long-take videos of deserted landscape with voice-over of interviewees.

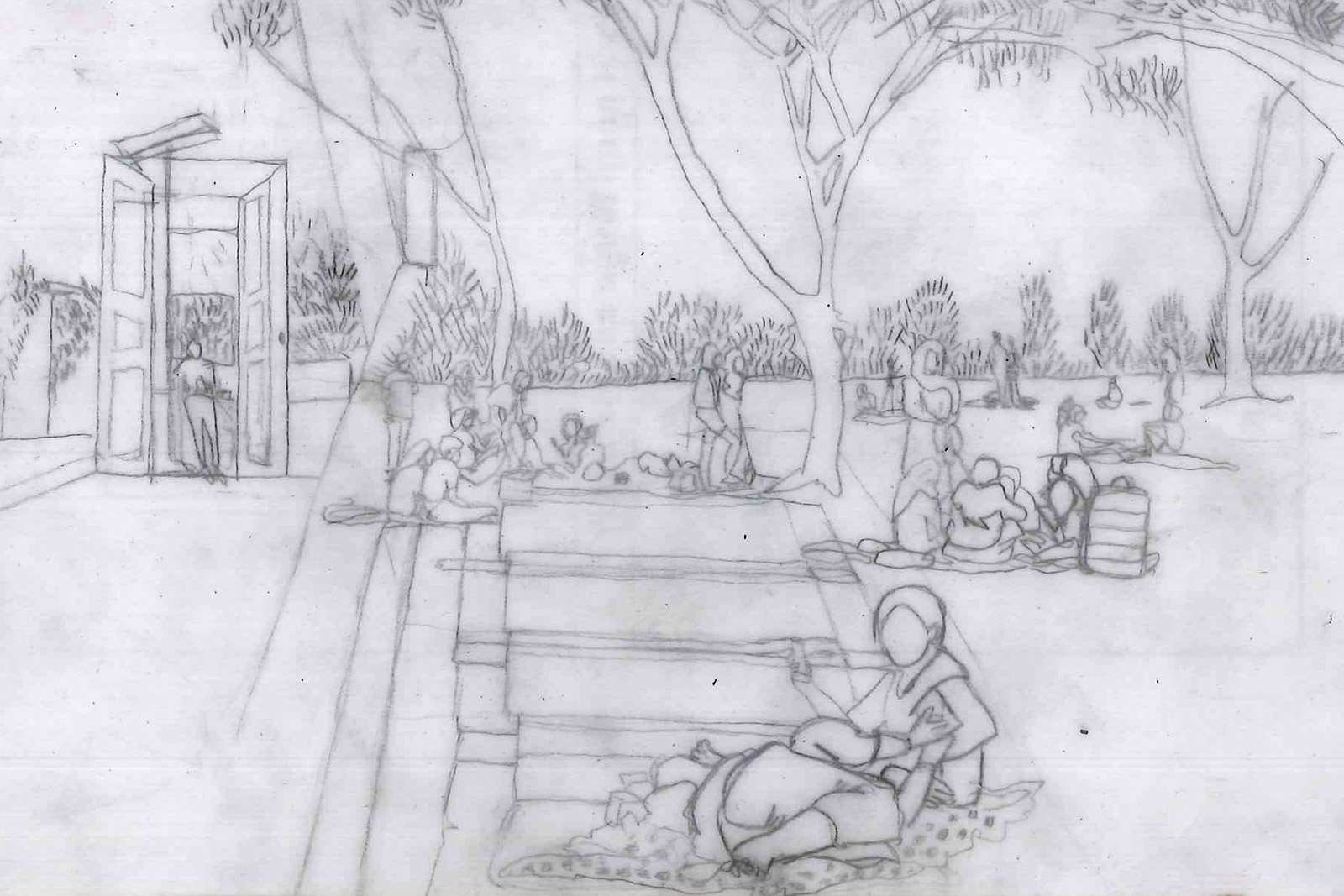

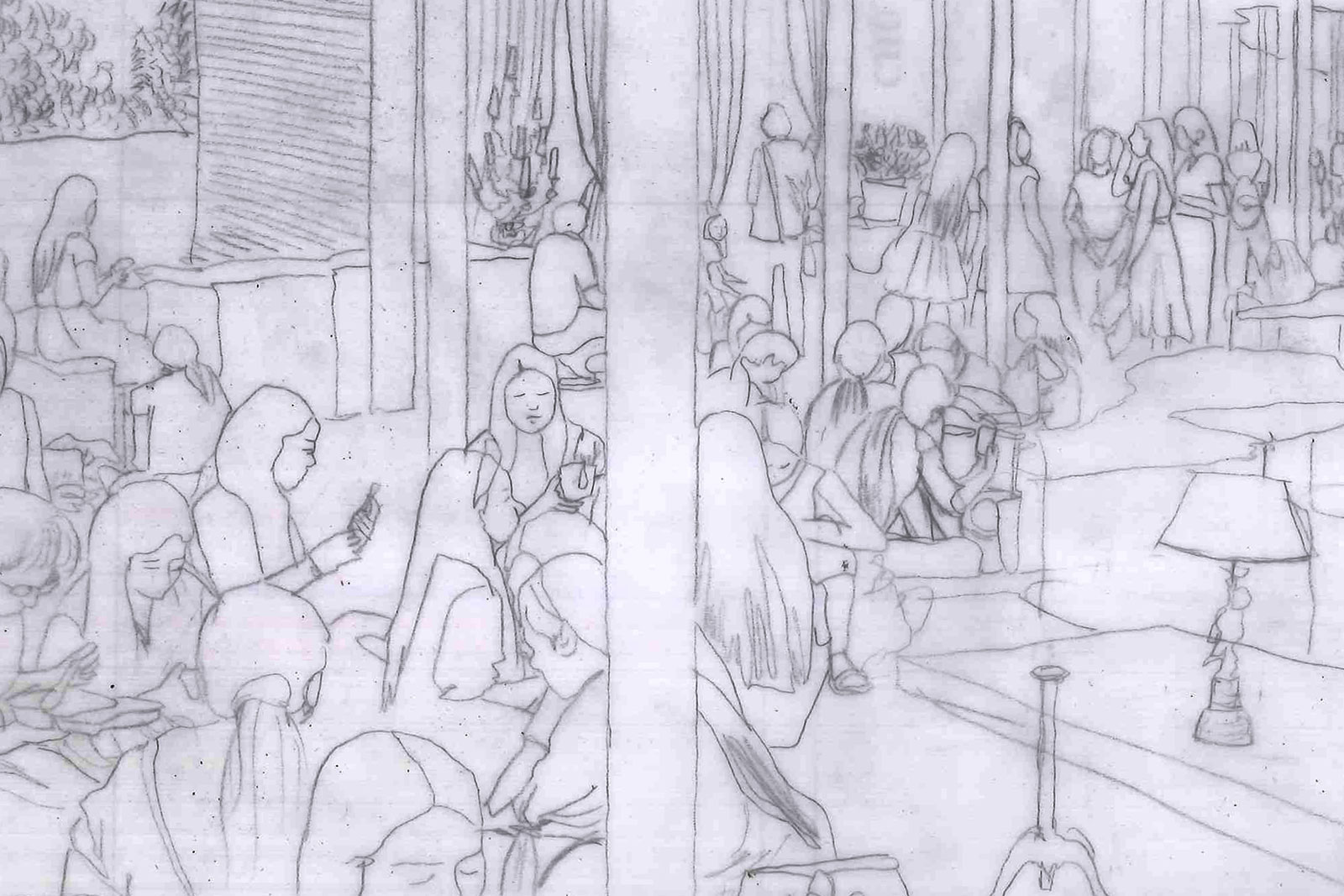

I find it reasonable to use the drawings to counterbalance the video work and highlight the contrast between absence and presence. The drawings actually come as an afterthought after I looked back at location-scout pictures, showing FDWs constantly on their phone, calling families when they picnic together. It pays homage to the idea of postcard, as an analogue communication device, where a person writes to another who is far away. I was also thinking about the often cliched postcard images of a place used to promote tourism. How about a kind of postcards to attract migrant workers?

During the last workshop I took with Jamie Maxtone-Graham at DocLab, we also had this assignment of the mental photograph, which ends up staying with me much longer even after the workshop ended. The core idea for this project is still about a mental photograph, a scene imprinted in your memory that you look forward to seeing. I am intrigued by what the camera cannot capture rather than what it can, and whether an image can be taken without a camera.

What were the challenges that you faced and how did you overcome them?

L: Most FDWs only have Sunday off for the whole week, meaning that I only had three weekends on site since I already spent one weekend location scouting. So my challenge is finding out a way to maximize my time on location and what to do for the rest of the week.

I was looking for activities on Sunday on a Facebook group for FDW, which involve hanging out in the plaza, getting essentials, getting together for a picnic, or doing sports. Eventually, I joined a public yoga session in the park on the first weekend, and was invited to a picnic with some workers under a bridge next Sunday. I went to a tower on Orchard which has all the clubs for foreign workers in Singapore, got into conversations with two drunk workers on their way to another after-party, and joined them for clubbing the following weekend. In conclusion, it’s a mix of planning and spontaneity, knowing what I want and being open to jump to different situations.

During the week I split my time between drawing, going to libraries, doing research, filming and editing.

K: Doing a residency in a foreign place really pushes me to find a way to make things work out. The language barrier is definitely a challenge, especially when I came here trying to find out about a local legend which is a historical topic. But it’s a blessing in disguise, since it really changes my approach. Instead of using interviews in my final work, I only use them to educate myself about the topic.

Four weeks is a very short time to get the whole picture. I’m thankful that we aren’t required to produce a complete work at the end of the program, so we could spend time gathering necessary information and materials. I went to Hoan Kiem lake multiple times to get a sense of place, visited libraries and museums, and arranged interviews together with an interpreter. I locked down specific people that I really wanted to meet, such as biologist Ha Dinh Duc and Natural Museum vice director Phan Ke Long, as well as interviewing locals around the lake, trying to get the gist of how people feel about the turtle/ legend.

How has the program changed you? Is there anything you wish you could have done?

L: Although one month is not long, it gave me a glimpse into the potential of a long term project, as well as the prospect and procedure of being a full time artist.

Honestly, I wished I was more physically fit because my schedule requires me to be long hours on location. I needed to take breaks in between and felt like I was losing time. I also wish I had more time to spend with my subjects. Even though I don’t get anything out of them, it still makes me happy.

K: My previous project was very long term, so this residency really changes the way I used to work. Sometimes I would take breaks, but this is just constant. It changes my discipline as an artist. It makes me think about how in the future I can plan and work things out in such a tight schedule.

I sincerely wish I could speak Vietnamese (laugh). As I was going around, I felt like I have missed many opportunities to interview people and find more about the subject because of the language barrier.

Based in Singapore, Kian Wee (b.1989) uses art making as a method of investigation of the world around him. Fascinated by humanity’s need for storytelling, Kian Wee’s current art practice explores the relationship between the society, its myth-making mechanisms, and the narratives brought about by it. Working primarily with photography, he looks into its efficacy as a form of myth-making tool, often bridging into other visual and sensory media as well. His work has been presented at the Jendela at Esplanade and The Substation, Singapore.

Lac Hoang (1995) is currently majoring in Art at Columbus College of Art & Design (2020). Her works include photographs, videos, and paintings that normally stem from found footage, exposing the obscure nature of memories and images. She is attracted to space within the house and its meaning in modern society when the boundary between the private and the public sphere is increasingly blurred. Thao conducts fashion photoshoots and works as a freelance art director under the name Lac Hoang. Her commercial projects interweave subjects of gender, urban life, and narcissism in the age of technology.