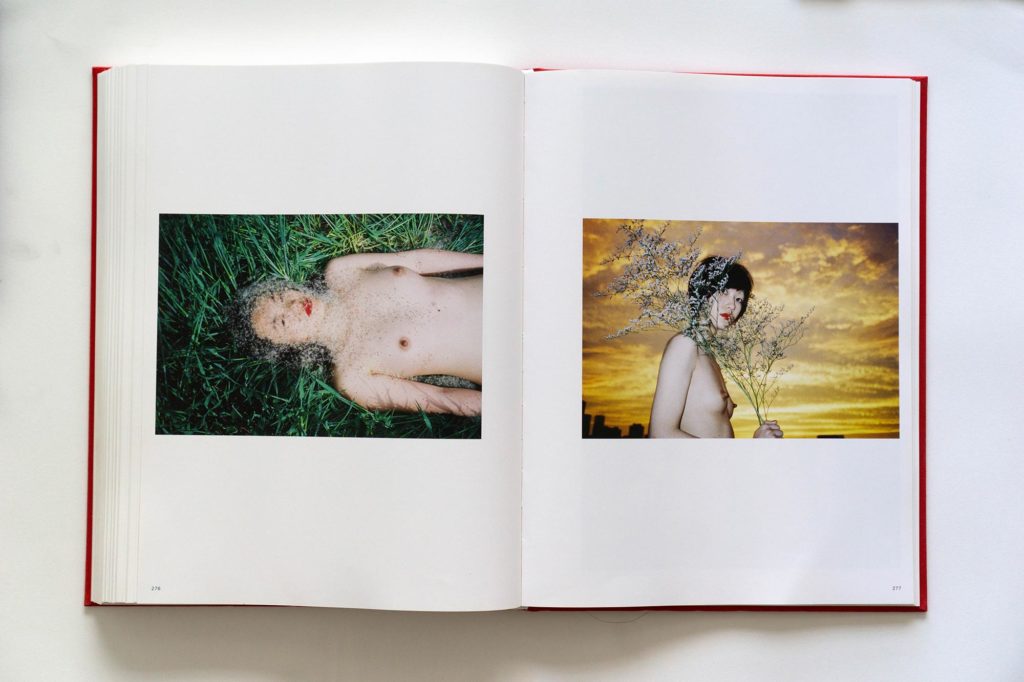

It’s both exhilarating and unnerving to hold in my hands for the first time a book of the late Chinese photographer-poet Ren Hang. Images that used to be mediated by a computer screen now materialize in print. Naked bodies – Ren’s primary subject matter presented in the book – invite to be caressed, simply as mere fingertips brushing against cellulose sheets when turning the pages.

Originally intended to be the first international collection of Ren Hang’s photographic works to celebrate his hitherto worldwide fame, the book, tersely named after the photographer, ends up being Taschen’s record of his legacy when the artist ended his life shortly after the first publication. It also takes on the role as a crucial reference text for Ren’s oeuvre, given that his original website, which used to be the main home of his works, has ceased to exist. On top of that, regulatory mechanisms of social media platforms often forbid his images from being presented as they are, always demanding mechanistic addition of chunky censor bars that unavoidably sully the spirit of his work.

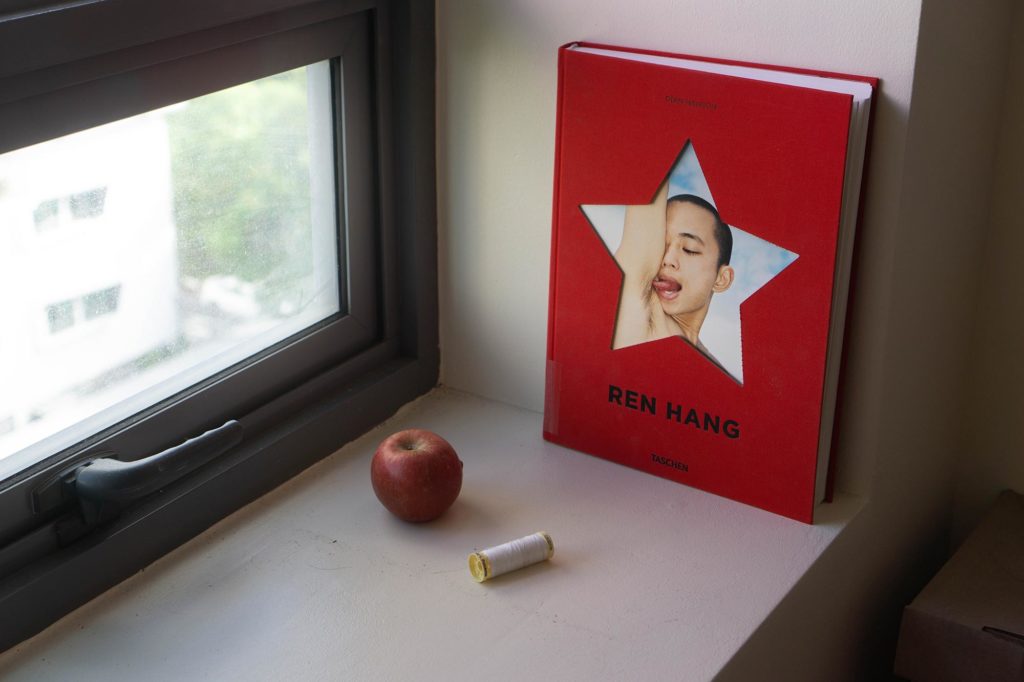

Weighing nearly two kilograms of more than 300 pages, clothed in a vibrantly red fabric hardcover, Ren Hang resists being taken lightly. As much as red is a color of passionate and seductive love, it’s also a sign of danger and violence, as if reading the book is analogous to tasting the forbidden fruit. Indeed, the cover is an allusion to China’s flag, where the yellow star is replaced by an image of the photographer’s long-time partner fondling his own armpit.

An attitude of irreverence, especially in relation to a repressive government, is a characteristic long ascribed to Ren’s practice. But any follower of Ren Hang would know that it is never his intention to make a political statement. What he found beautiful, he shot obsessively. More often than not, beauty in his private realm of existence – naked porcelain bodies with human genitals in full display – is never left as it is, but is always moralized. Standing in opposition to China’s public morality, his works landed him several arrests. These incidents to him were not solely an exercise of power but mere inconveniences to his life-long goal – to deliver snapshots of beauty to the people of his beloved country.

This is quite different from what the book sets out to do: to showcase to the international audience brazen Chinese youths in full embrace of their sexuality and perversion. “I don’t want others to have the impression that Chinese people are robots with no cocks or pussies, or they do have sexual genitals but always keep them as some secret treasures. I want to say that our cocks and pussies are not embarrassing at all,” quoted Ren in the introductory text.

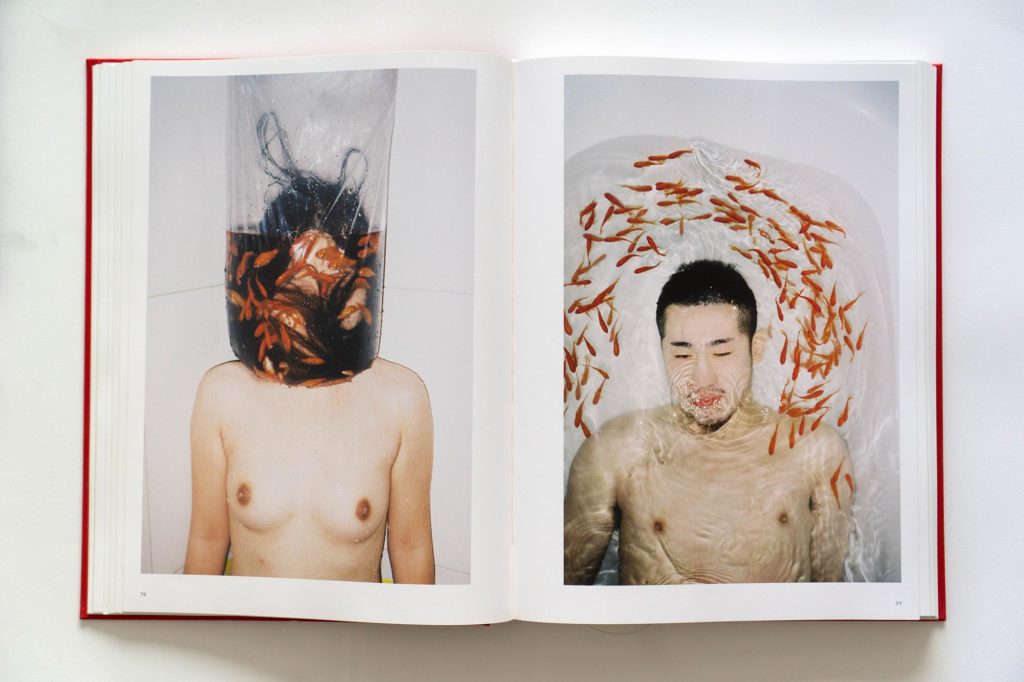

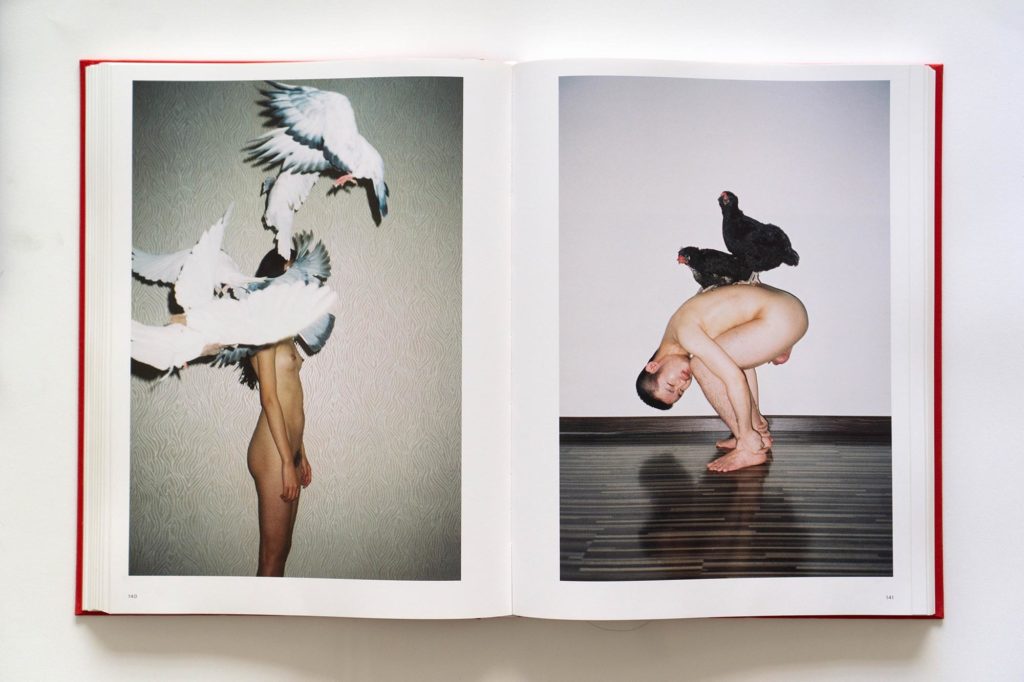

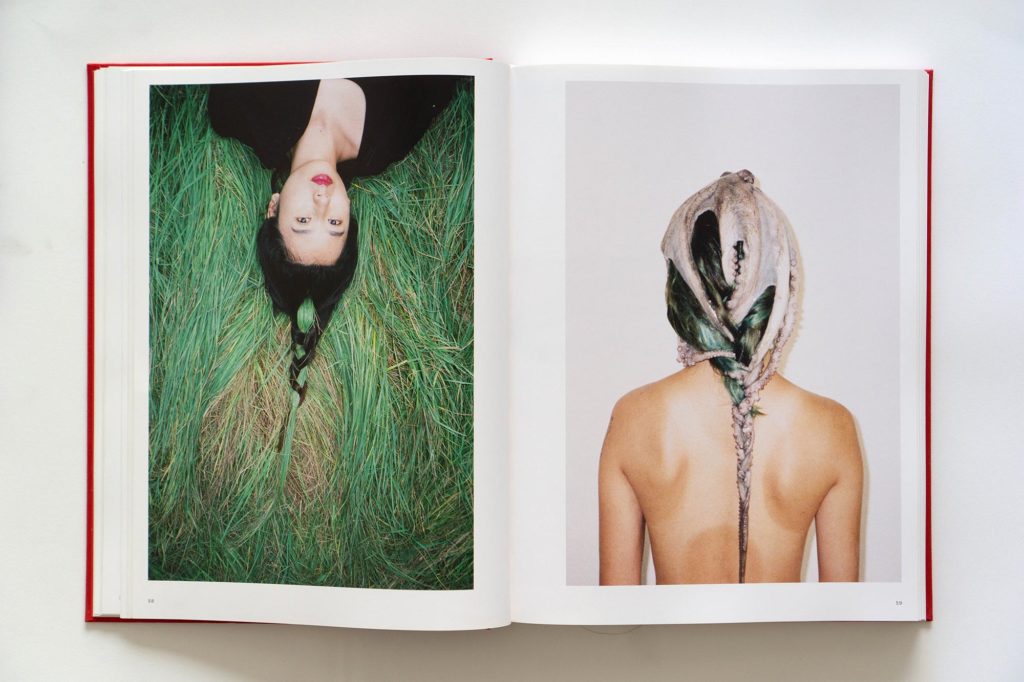

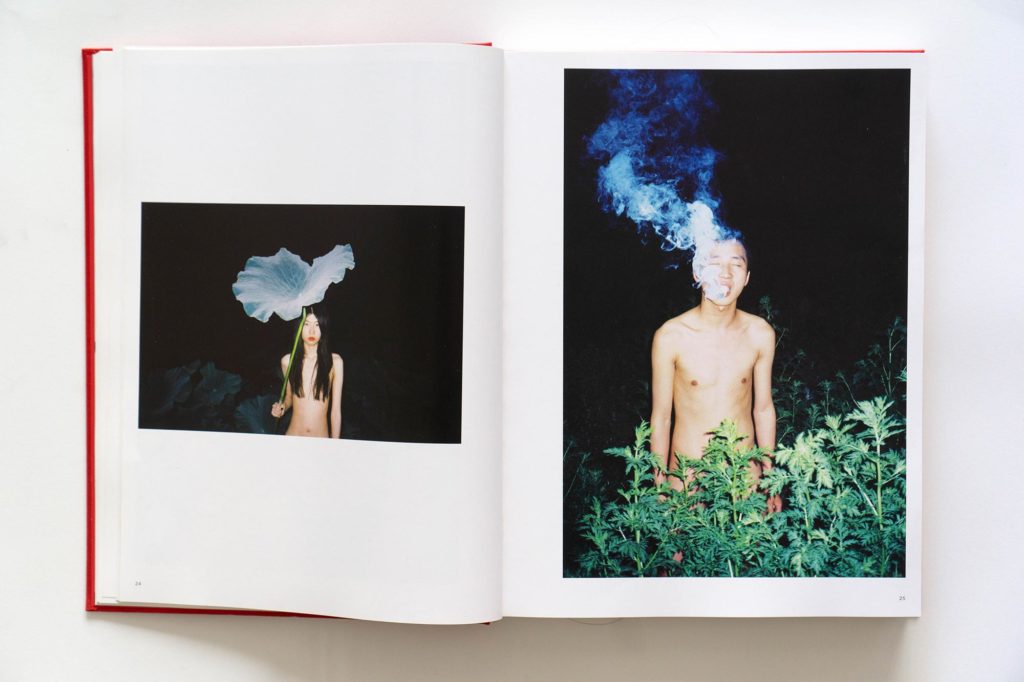

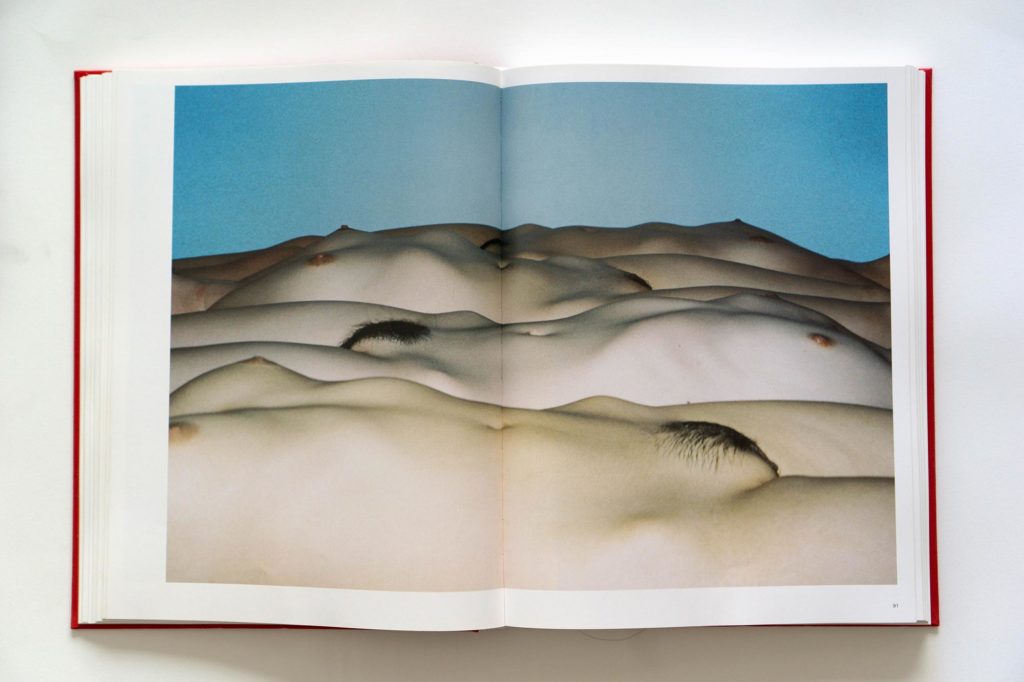

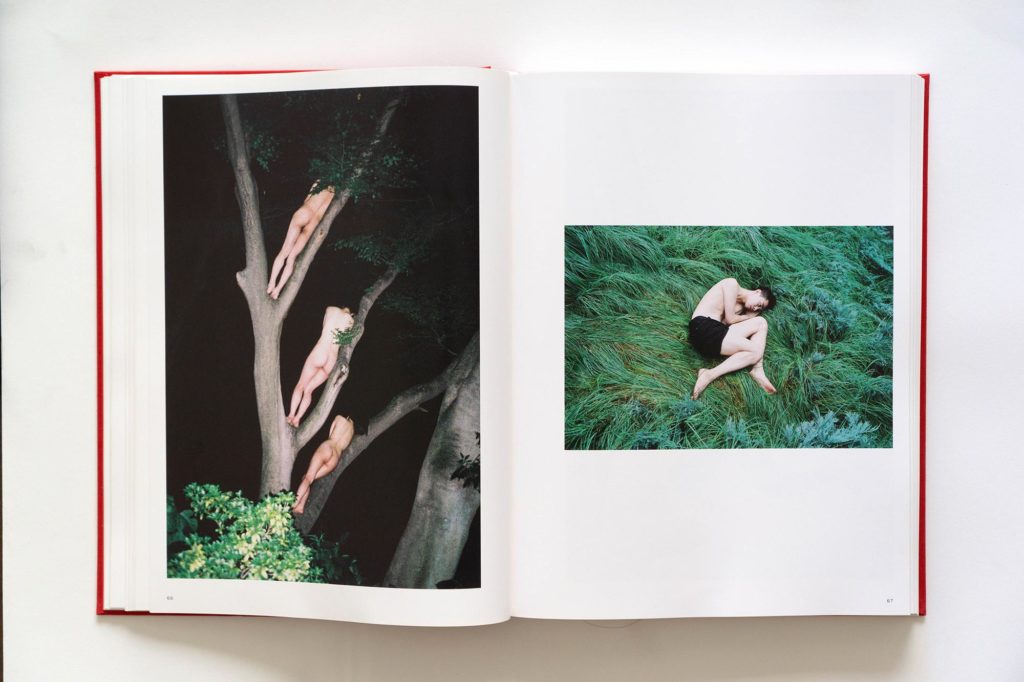

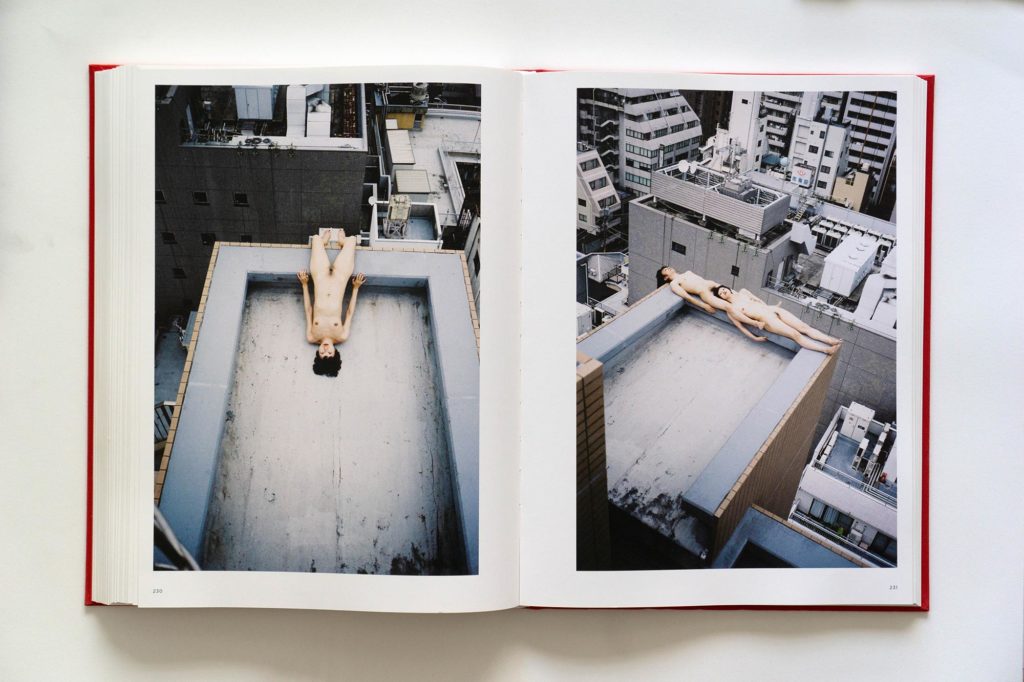

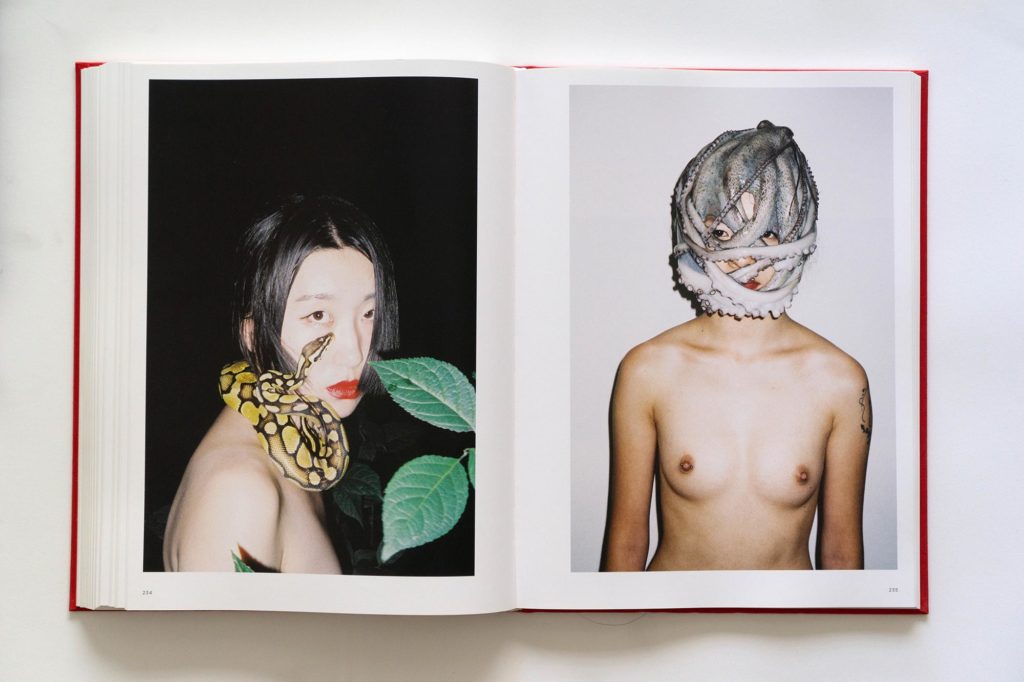

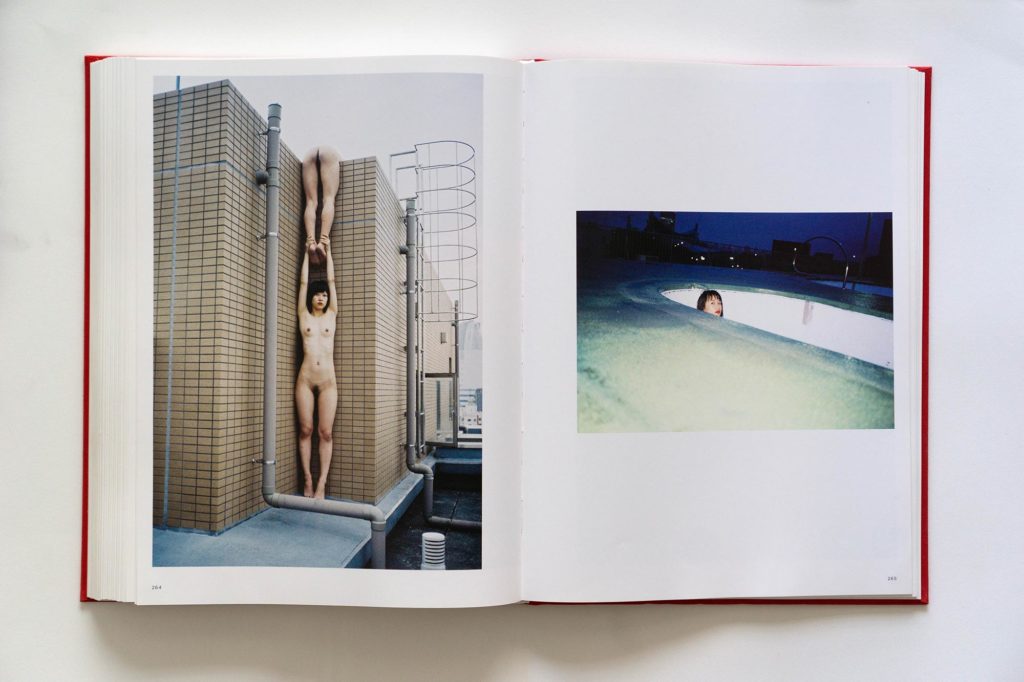

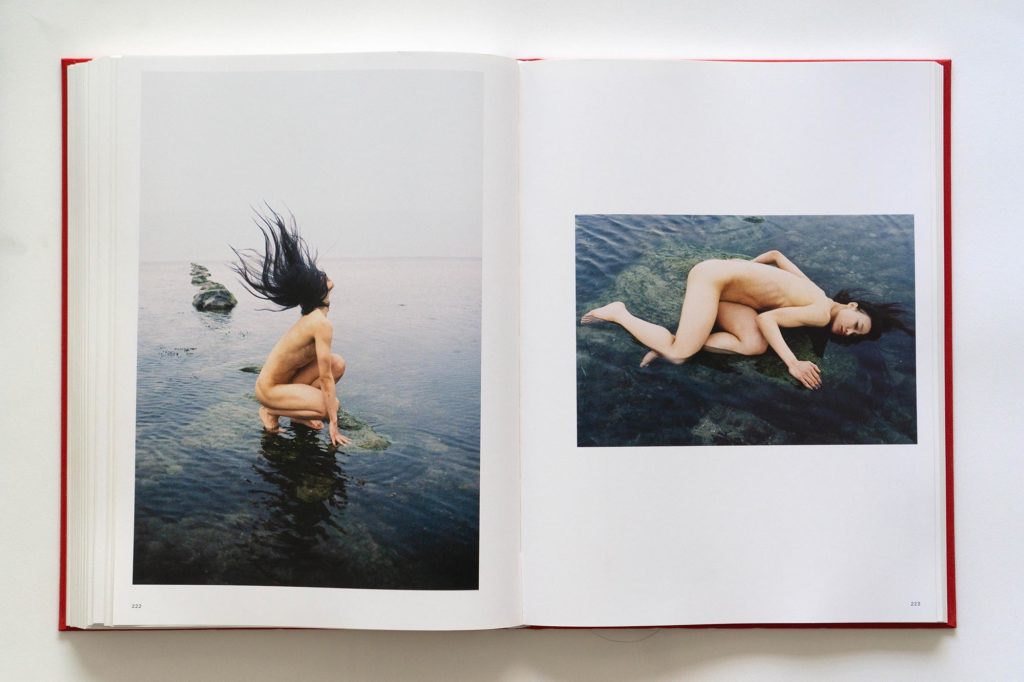

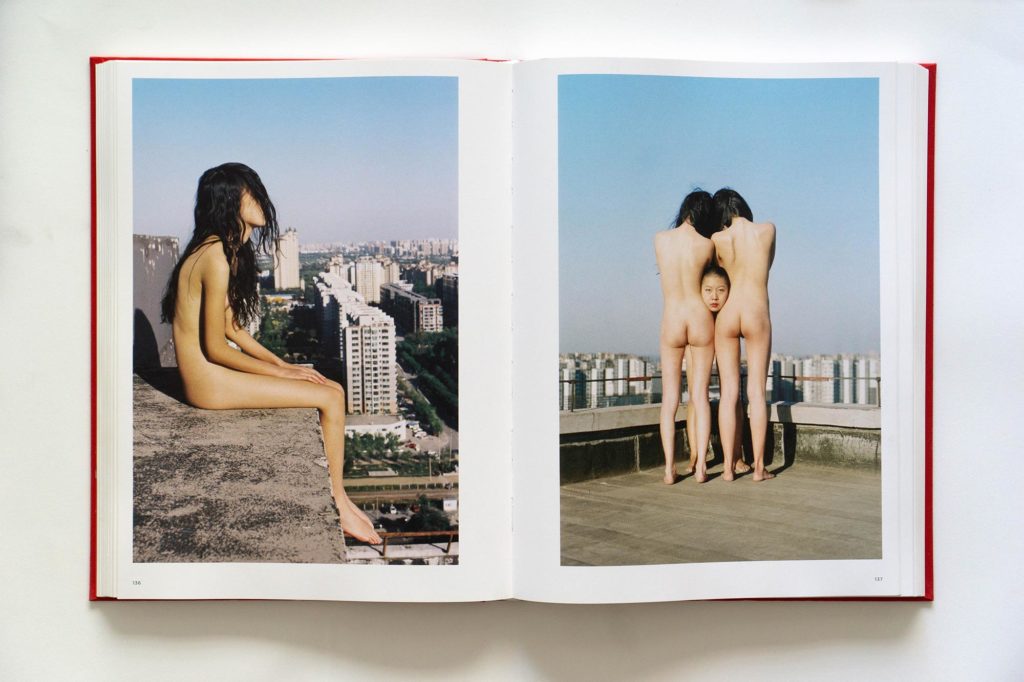

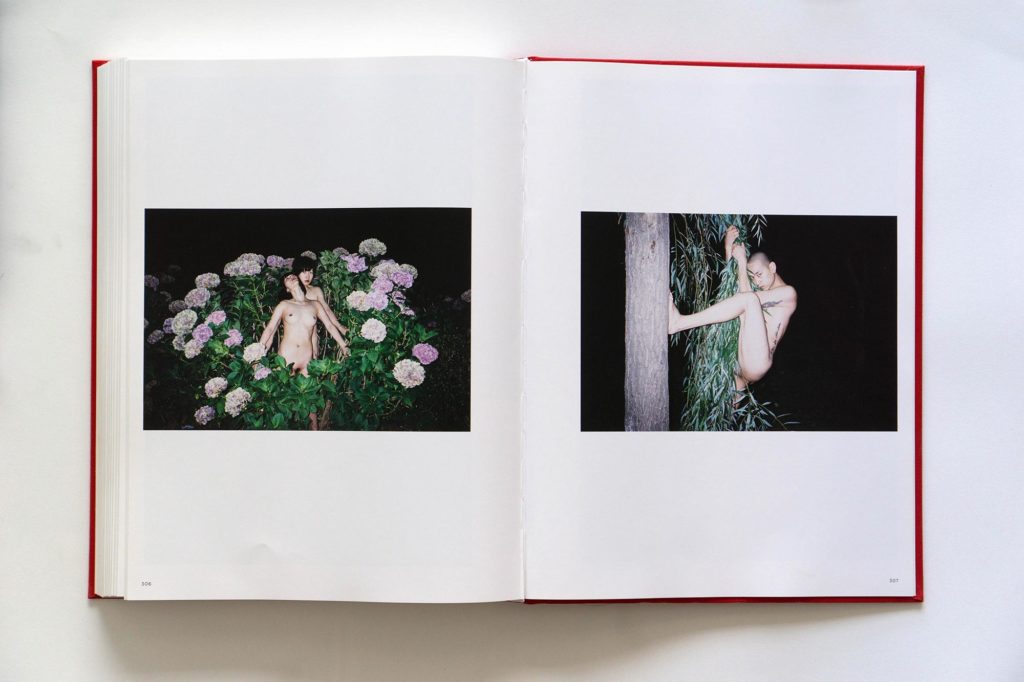

The book is a deluge of images – the externalization of Ren’s obsession with beauty. He shot lanky, almost always unclothed Chinese youths with jetblack hair, often long for girls and cut short for boys, and immaculate pale skin illuminated by the direct flash. Facing the camera are outstretched vulvas and erected penises, adorned with cigarettes and lipstick smears. Flowers and animals are recurrent motifs, sometimes to a simultaneously disturbing and humorous effect: thorny rose stalks lie haphazardly across exposed groins, and an octopus sits on a model’s head with tentacles braided in her hair. Many photos render the viewer a voyeur of passionate lovemaking, taking place on a rooftop overlooking an anonymous urban backdrop, in nature surrounded by lush greeneries, or even in a fish tank incongruously situated in a hotel room. Acts of intimacy range from embraces and locked lips to feet licking and pissing at each other. Some snapshots are led by a concern of formal beauty: the heads and arms of a group of women criss-cross in compliance with the radial geometry of a star, or a man crouches in the very center of the frame, his eyes hidden behind two symmetrically placed penises. At times, models are reduced to their body parts, composed into uncanny sculptures – torsos and buttocks lining up one after another, suggestive of undulating sands, or bodies draping over a tree branch, their slim legs dangling towards the viewer and spreading just wide enough to offer an unobstructed view of their privates.

These images should not be taken to represent Chinese youths, for they encompass only a minority who are unafraid, or maybe foolish enough, to publicly display what is generally kept in private. Still, thanks to Ren’s influence, they prove critical to our knowledge of Asian sexuality. In contemporary times, the openness to talk about sex and the relative freedom of sexual expression are often regarded as a Euro-American way of life. Meanwhile, Asian cultures generally relegate any matter related to sex to the realm of taboos. On top of that, operating on a logic of binary oppositions, the predominant Western imagination conceives Asian sexuality as subservient: Asian men are seen as scrawny, sexually inept individuals in relation to hunky, masculine white men, while Asian women inhabit an exotic space of sexual fantasy.

Ren’s photographs untangle Asian sexuality from this web of significance. As much as they are an indulgence for the artist, his friends, and his community, they are proof that Asians of any gender and sexual orientation own their sexuality. Their erotic desires and carnal pleasures are for them, and them alone, to embrace; whether or not these images transgress societal moral codes or serve someone else’s fantasies is secondary.

It should be cautioned that the choice to see Ren’s primary subject matter, which is Chinese youths, as Asians can be problematic. To use the term “Asian” is to conflate a myriad of identities with distinct nuances and histories. To my knowledge, Ren never spoke of Asians, only his countrymen. The colloquial usage of the term “Asian” here simply refers to any reader who happens to identify with this race and, in our interpretive endeavor, sees in his photographs snippets of their own sexuality. For them, Ren’s images offer a wealth of sensual bodies that resemble their own more than those captured by Ryan McGinley and Terry Richardson. They possibly also find in his inventive use of props and backdrops a distinctive flavor rooted in a locale closer to home than the land of Guy Bourdin and Robert Mapplethorpe. Ren’s works offer a slice of the vast terrain of Asian sexuality. In his recorded gestures of profanity, Asian readers could affirm their sexual expression, externalize troubled feelings, or simply find normalcy in the purported “abnormal”.

It’s of no doubt that the photobook achieves what it sets out to do: to debunk the myth about Chinese, and by extension Asian, sexuality. But I still have my reservations about the veracity of its depiction of Ren Hang as an artist. This is not to say that the shamelessness and gross indecency misrepresent the photographer; in fact, he preferred pornography to eroticism as a descriptor of his works. What I find uneasy is the rather one-dimensional portrayal of Ren, especially when compared with his monthly self-published monographs “on love and survival” in 2016. For instance, the June issue is a series of diptychs that pair up choppy waters with a naked female models inhabiting the same landscape at night; the November issue interweaves a male subject, fully clothed for the most part, with banal shots of nature. These self-publications suggest a noticeably different Ren Hang, someone with layered thematic concerns as well as a decisive creative direction of the reading experience. This stands in stark contrast with the book which seems to sensationalize rather than present a nuanced characterization of the photographer’s practice.

Taschen’s presentation might suffice as an overview for the international audience. But upon closer look, it becomes evident that the book rehashes what Ren is primarily known for instead of highlighting the subtleties of his practice. In subverting the West’s conception of Chinese sexuality by inciting elements of shock and perversion, the book inadvertently racializes the subjects: the models are registered as Chinese or Asian before they are seen as sexualized bodies. The white gaze persists, continuing to see Asian bodies as an exotic Other.

Now that Ren is no longer with us, he has no way to speak for himself. But maybe this is trivial; he never seemed to mind how his works were presented. As long as his people – the youths of China, his followers, or simply friends and lover – see him and relish his creations, nothing else really matters. If anything at all.