At the apex of the COVID-19 pandemic, many things felt out of place. Talks and photos of holiday destinations, once taken for granted whenever the season comes, were relegated to the what-ifs and the wishful thinking. The hustle and bustle of city life before the outbreak suddenly took on a nostalgic and at times incongruous quality. It was supplanted by images of people, while donning face masks, hurriedly traversing the urbanscape, alone.

In this regard, Nguan’s photographs seem more relatable than ever.

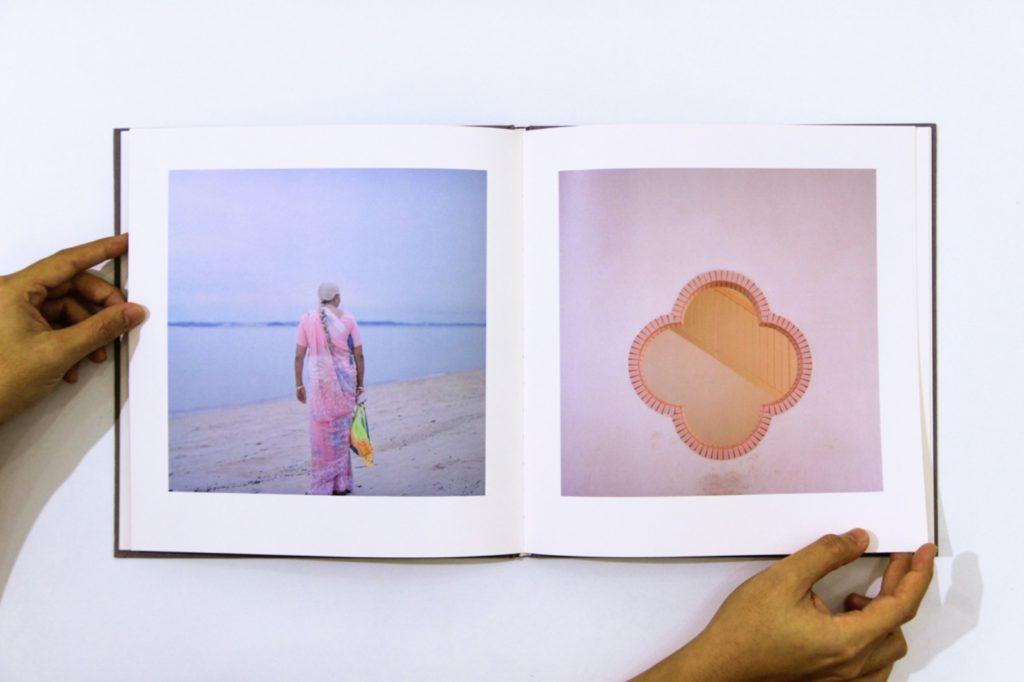

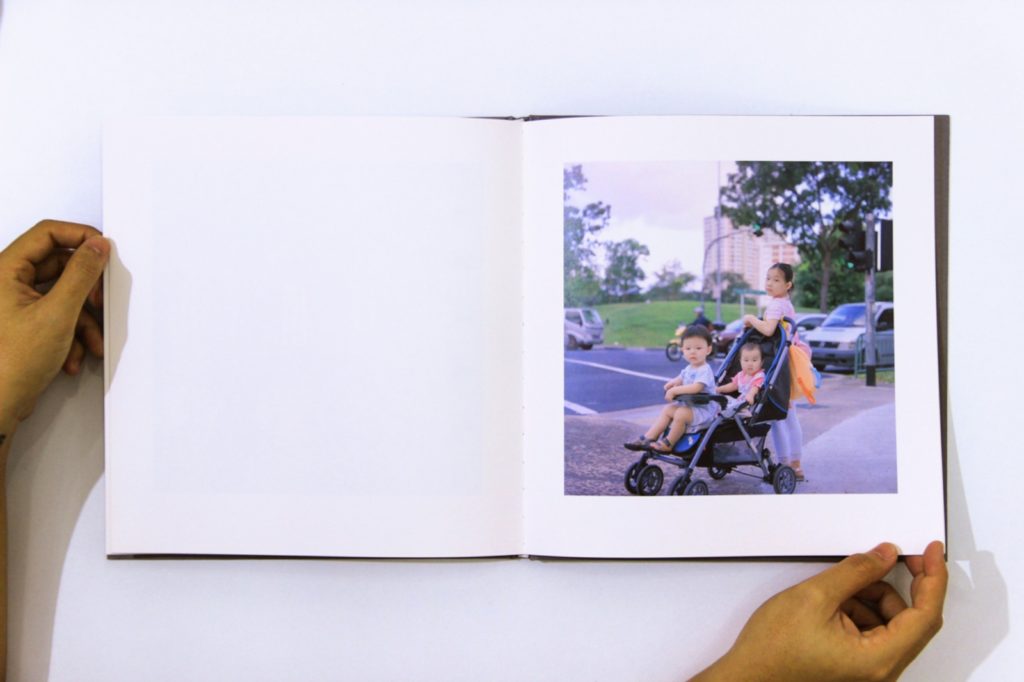

The Singaporean photographer is known for portraits of urban dwellers and still-life sceneries, often imbued with a mystical pastel palette. They wrap ultra-modern cities like Los Angeles and Singapore in a lethargic air, like an extension of Sofia Coppola’s vision of Tokyo in Lost In Translation. In the pre-pandemic times, these works would have appeared uncanny; but fascinatingly, they speak volumes about what we feel now in the midst of the crisis.

I would have missed this realization had it not been for Nguan’s old works re-surfacing again on social media. The pandemic breaks our sense of time up into two very distinct temporalities: before and after the outbreak. Yet, Nguan’s curation of his old and newly created photos on his social media accounts offers a continuity that overrides this demarcation.

I was compelled to reach out to Nguan in an attempt to make sense of this unexpected sustained coherence amid a time of disruption. I did have my own hypothesis. His works could foreshadow the current reality, possibly because they manage to capture the elusive conditions of urban life – listlessness, longing, and loneliness – which have always been there but only get exposed and magnified by the recent pandemic.

Nguan reveals in a previous interview that highlighting these sentiments is his way of giving a counter-narrative to the ultra-modern Singapore. Life in this urban jungle – a densely populated, fast-paced environment of competition governed by the logic of technocracy that champions science and technology – ushers in feelings of isolation and alienation.

The persistent fatigue is not the only truth that gets exposed by the health crisis. Singapore makes international headlines for the systemic discrimination brought forth by the pandemic: a disproportionate number of coronavirus cases are among migrants workers, resulted from the ease of transmission in their overcrowded dormitories. The pandemic has also witnessed Singapore’s General Election, a four-yearly event that can get emotional for its citizens whose hopes for change of leadership vary. Once again, Nguan’s old photographs make a presence in tandem with the prevailing stress on the social fabric of Singapore.

If we could extrapolate from his works and make a claim about the imminent direction of our urban life, then perhaps it is a testament to the power of photography. The act of viewing a photograph is retrospective; it’s always a moment of the past chemically fixed onto a physical surface or registered as digital signals by sensors. Yet great photographs still resonate with us, for they capture an essence to life that persists beyond the constraint of time, prompting us to question the present and speculate about what the future holds.

Does this time alter the way you approach photography, for both the act of making and viewing?

Yes – my favorite thing was to photograph in crowds, and I became really good at it, but the pandemic has made it a fairly redundant skill. I expect to be focusing on landscapes and still lifes for the foreseeable future. I think of the pictures I make of people in public as portraits, which Wikipedia defines as an “artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expression is predominant”, so I have limited interest in photographing people in masks. On recent occasions where I’ve come across people without masks, I was hesitant to photograph them because I was aware that they might have thought that I was trying to catch them flouting the law.

From what I observe, your works feature mainly portraits of a single individual, or still life of the urban scenery. The subjects are often alone or seem very mentally distanced from the crowd, while the deserted scenes evoke a sense of quietude and serenity. Strangely, at least for me, these translate very well to the pandemic. Seeing these photographs is thus akin to witnessing a fairytale version of the present, where people need not wear masks and the scenery is graced with the pastel tones.

I like this interpretation a lot. It’s possible that the conditions imposed by the pandemic have nudged your perception of the world closer to mine. At the end of How Loneliness Goes, I wrote that I wanted my work to “wander in my stead”, which might have seemed like a rather curious wish at the time, but is probably quite relatable now that we are all trapped in our own countries, homes and heads.

The recognition that your works become even more relatable during this time makes me wonder what about them that enables such, as if the present (when you took the photos) can anticipate the future (our present right now). My hypothesis is that your deliberate attempt to capture the elusive modern loneliness and urban fatigue in fact distills a thinly veiled truth to life that becomes fully symptomatic when triggered by this pandemic. The alterations to our daily life can be thought of at once necessary to tackle the pandemic, but also a direct outcome of techno-modernity on a hyperdrive. Do you agree with this claim?

Absolutely. I’ve just finished editing my next book, which comprises the work that I made on the Staten Island Ferry between 2014 and 2019, and nearly a third of its pictures are of riders staring at their mobile phones. Initially, I thought: surely I’ve included too many pictures of people on their phones? But then I decided that I couldn’t accurately depict modern life without depicting people on their phones. If Friedrich or Hopper were alive today, they’d be painting pictures of people on their phones.

For most of your works on your social and books, a caption is absent. I believe that this lack of a text as a harbor (or tyranny?) for meaning contributes to the mutability of your images. However, some recent posts include a caption of where and when the photo was taken. If I were to again speculate, does it have to do with wanting to make your statements clearer with respect to certain prevailing social issues, such as about the migrant workers and the general election?

Exactly. I have the greatest respect for the authority of words, and the imagination can run freer when they are not in charge.

I’ve always shared a mix of old and new pictures on my social media, but this has become more obvious during the pandemic because of the absence of masks and social distancing in the pre-COVID work. The world has changed so radically and so quickly that the sight of a stranger’s unadorned face is suddenly nostalgia.

Regarding the caption I included for the image of migrant workers after their cricket game, I was sensitive to the fact that only a portion of my online audience live in Singapore, and I thought that more context was necessary for everyone to read my intentions. I also specified the date because I thought it was important to know that the photo was taken pre-COVID outbreak, and social distancing rules were not being broken by the workers.

There is a revival of your past works on your social media. How about photographs made in the now?

I’ve been continuing to examine the everyday landscape in Singapore during the pandemic, and in these pictures are incidental signs of the present crisis: social distancing markers, halted construction projects, face masks hanging on clotheslines alongside towels and underwear. Sometimes it’s the little details that best describe their times.

Nguan’s photographs contemplate life and longing in the world’s biggest cities. He was born and raised in Singapore and graduated from Northwestern University with a degree in Film and Video Production. Nguan’s first monograph, Shibuya, was featured on The Telegraph and named in PDN Photo Annual as one of the best photo books of 2010. His second book, How Loneliness Goes, was called “a masterful color portrait of quiet urban lives” by American Photo in 2013. Nguan’s photographs are in the permanent collection of the Singapore Art Museum.