As a Vietnamese-Australian, artist Phuong Ngo is perpetually concerned with the question of where he is from. His visual artworks utilize photography as a research method to inquire into his cultural identity formation in connection with broader history. Here, Phuong Ngo spoke to Matca about the potential of photography beyond the printed surface, how vernacular photographs provide an alternative perspective of war and conflict, and the complexity of being an Australian born Vietnamese.

How does photography fit into your practice of visual arts?

My practice is not a conventional photographic one, and I align closely with conceptually driven art. Having said that, I can say that the foundation of my practice is lens focused. I’m interested in my heritage and my family history, but in the wider history of the Vietnamese diaspora and Vietnamese history itself, and this goes through the history of colonialism, war, conflict and imperialism as well. So my practice actually sits around the potential of photography, what it can tell us with the help of hindsight, history and time, and what research it can lead to.

How did this interest in photography come about in your career?

Being the child of refugees, art wasn’t exactly a space in which you could explore while under your parents’ roof. I began with a degree in Asian Studies, then I started doing a research degree in Politics and it wasn’t quite going the way I wanted it to. It was during that period that I started revisiting ideas around art and what art could be, and that led me to leave my studies and enroll in art school.

My interest in photography was pretty hazard. I needed to apply for art school but I hadn’t done anything artistic in a good seven years, so I decided to pick up a camera and have a play with it. I started looking at the history of my family, and the closest one to me was the Vietnamese refugee narrative. The Vietnam War became very prominent in my research because it was the flashpoint in trying to understand why I exist the way that I do. When it came to image making the photographic medium just happened to be the most prolific, so this became the medium which I focus on.

This investigation into your personal history and that of the Vietnamese diaspora is reflected in The Vietnam Archive Project. How has the archive shaped and informed your practice?

The archive was quite a fortuitous project in how it began. At that point I almost stopped thinking about making photos in the traditional sense and started to play with different ways in which photos can be extended. I was doing research online and came across a group of slides for sales on eBay from an American soldier whose wife was selling off after he passed away. It was kind of odd that I could buy them, like they were commodified, and there was no real preciousness to the objects. Most of my materials come from the United States and France, it’s a lot harder to get Australian materials. Right now the archive consists of about 20,000 items, predominantly photos and slides but other objects, books and family photos as well.

I have certain boundaries with which I collected. They have to be almost complete sets, full photo album or full set of slides, because I’m collecting the whole narrative, the entire experience of the war. Another thing is that my practice is heavily entrenched in research, and I almost view research as an actual art in itself. The archive is a massive repository of research for me. It’s also an artwork, a reflection of how I think, how I curate and how I collect.

What are some patterns that come out of the photos in the archive, considering the fact that they were mostly taken by American soldiers?

What I learned from these sets is that these are very young men – the framing of the lens and the subject matter are really indicative of young, curious people who don’t know what exactly they are doing. A lot of them are just mucking around, meeting local girls, going to local countries that are close by. I do have one grouping from a higher official which is largely around holidays, many shots from airplanes, nothing in the field or on the frontline.

Another pattern is that Park Lane is a cigarette brand that was sold in South East Asia during the war. We’re talking about the 1970’s and 60’s – it was the time of free love and the hippie movement in America and in Australia, and the drug of choice was marijuana. And Park Lane cigarette was how marijuana was sold in Saigon. Then when you go back and look at these photos, you realize that these guys are actually really high. It’s quite an odd thing to think that these men are fighting in a war but at the same time they belonged to this kind of radical subculture, and back home in America people were very much anti what they were doing.

These are aspects which are almost completely absent from the popular imagery of the Vietnam War. If you contrast these vernacular photographs to the iconic press photos, how would you say they are different?

It’s almost the complete antithesis of what the press photos are. They are not looking for the drama, they are showing a much more complete picture of what happened during the war from a particular perspective. Even though it’s only on one side, it’s a much more holistic and personal illustration one. Press photos don’t necessarily have names and things attached on them, but with some of these you see their name on their lapel or on their shoulder, and you can actually find out who they were.

Tell us about your recent exhibition of the archive – how did you present the photos combining different materials?

The first work in that exhibition, Colony, uses these found photos that I found in a market place in Saigon. In each one of these portraits, the face of Alexandre de Rhodes is pasted over Vietnamese people’s face. The work is looking at the way in which identity is formed by colonial history, how the French has influenced Vietnamese identity but there is also the thousand years of Chinese colonialism. That’s why the whole structure that hangs these photos is a very Chinese one – the red color, the hanging, the knots are all Chinese symbolic objects.

Another work is called The Hunt. It’s an installation that consists of one light box showing a photograph of a tiger skin and a series of digitally woven blankets featuring dead bodies of South Vietnamese soldiers. It looks at the commodification of soldiers into tools of war, the mechanization of that and the mechanization process of creating these blankets, and subsequently, what is war but the economics of death.

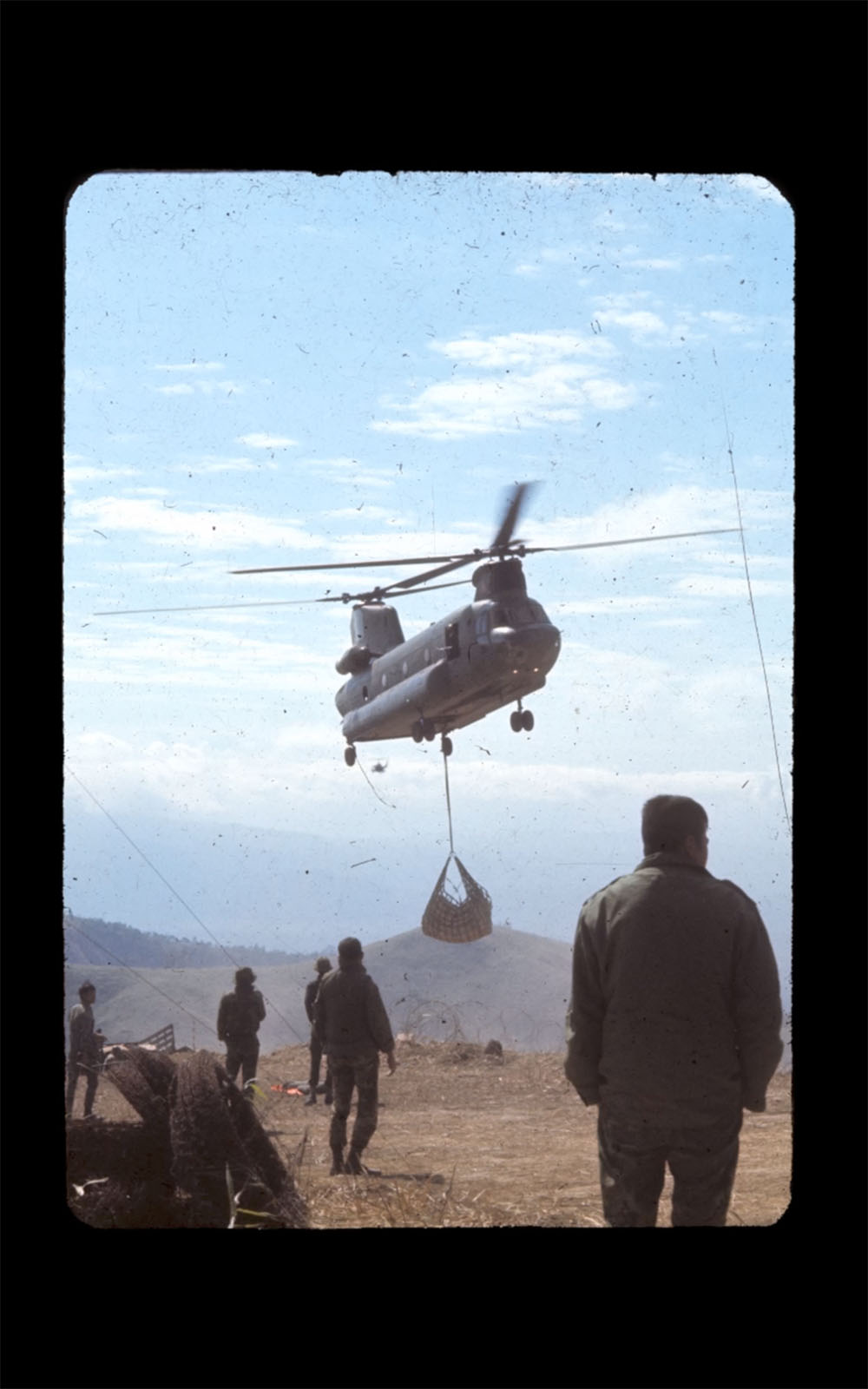

The final work that I’ll be talking about is probably the first work that I made out of the archive, Apocalypse Now and Then. It takes a series of still shots of a chopper going back and forward in this really bad loop based on images in the archive. It’s soundtracked with Wagner’s Ride of Valkyries and this famous quote of “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” from Apocalypse now. The work explores the space between fictionalized history and history itself, and how over time one might replace the other. It’s primarily questioning the cinematic universe, the complexity that sits around how we get information, what component of history is being presented and what gaps is being left or fleshed out.

You openly talk about failures – in getting back to the refugee camp and reenacting your parents’ traumatic boat journey to Australia. Why do you think they are failures? What’s the merit in doing something that cannot work?

I had very romantic notions about gaining insight into my parents’ experiences by physically retracing and filming key places of their displacement. The first work that I made out of the family history is My Dad the People Smuggler, which is the footage that I shot retracing their journey from Vietnam to the Bidong Island. I visited the refugee camp, got on a boat, then went back to this private beach resort, looking out from it and seeing the refugee camp on the coastline. And in realizing that my experience of the place was totally nothing like my parents’, I felt like I failed in my attempt.

There was a beauty in that failure because I tried to do something to honor my parents and to learn. This inherent failure will always happen regardless of what I do to engage with the narrative on more than an oral history perspective. In acknowledging that everything will be a beautiful failure, I decided to keep going.

From my observation, overseas Vietnamese artists tend to make work revolving around the Vietnam/American War and their conflicted identity. Why do you think such tendency exists?

As a person who is displaced, not by choice but by circumstances, – and I feel like this is probably the case for a lot of creative diasporic artists in Australia and in Western countries, you exist in a space where you’re reminded constantly that you don’t belong. From a historic standpoint, it’s part of that inherited trauma that you have from being a child of boat people as well. I was born in Australia but I cannot go anywhere in this country without being asked where I’m from. And when I go back to Vietnam, for some reason it’s really obvious that I don’t belong there either, so I keep getting asked where I come from there as well. All of my works are situated around the idea of unpacking that question, where you’re from. In questioning that, you do get interested in broader history.

Could you give your definition of Vietnameseness?

Speaking for my own Vietnameseness – and I cannot say this strong enough, I can’t speak for anybody else’s – is very much situated in this idea of what it means to exist as a Vietnamese person outside of Vietnam. It’s one that’s to find by key events in history that predate my existence and by trying to understand how these dominos have fallen to create who I am. I guess my Vietnameseness is built around questions, questions of who I am being what history has created me and how far back in history do I need to go to understand that. So I’m answering your question with a lot of big questions but I feel that that’s the right thing for me.

Phuong Ngo is a contemporary visual artist based in Melbourne. He completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts at RMIT University in 2012. His practice spans across multiple media such as photography, video, installation and performance. He is currently developing Hyphenated Projects, a platform for presenting Asian-Australian art in Victoria, and shares a collaborative practice with Hwafern Quach, Slippage.

Follow him on Instagram.

Nguyễn Phương Thảo received a master’s degree in Communication studies with a focus on the visual culture from Université de Toulouse Jean Jaurès (France). Her writings have been published on Diggit Magazine.

Connect with her on Facebook.