We re-publish this article to commemorate the life and work of artist Dinh Q. Lê (Lê Quang Đỉnh) who has left us too soon. It is part of ‘An Assignment on Memory’, a series of essays by the young writer Carmen Cortizas Fontan, first launched in December 2022. This project was supported by the Nguyen Art Foundation and made possible with support from the artist Nguyen Van Cuong. The article is translated by Nguyen Thanh Tam.

In the temples of Angkor Wat, rows upon rows of headless Buddha statues sit on old stone. The bodies have been chipped with time, and scratches of violence can be seen around the necks. The heads have been taken to different cities around the world. In their new homes, they are often placed on a white pedestal, with a plexiglass on top and called pieces of art.

Although both the ‘bodied’ and the ‘disembodied’ share the same painful history, their decades of separation have caused them to become independent of each other. This story directly speaks to the violent looting of South East Asian heritage in the process of colonization, but to artist Dinh Q. Lê, it also embodies a portrait of himself, and of others who have experienced the dichotomy of being a refugee.

Having grown up with America’s portrayal of Vietnam since he arrived there at the age of ten, Dinh is especially aware of the Western-centric narratives that continuously dominate history. His work is an attempt to give unheard stories an opportunity to integrate and infiltrate into mainstream historical discourse, thus contributing to a more complex understanding of Vietnamese identity – beyond that of an extra in American war movies.

Since his youth, Dinh has been deeply interested in the role of the photographer, and the influence that photographs can have in different socio-political contexts. While attending the New York School of Visual Arts, he began to research the photographic narrative produced by Vietnamese photojournalists on the Viet Minh side1– whose images weren’t put on the front pages of Life Magazine or the New York Times. With a research grant, Dinh returned to Vietnam in 1992, where in Hanoi, he was able to find a group of photojournalists that let him view their mostly unseen photographs. Although the photographs were laid on the table for him, he was not permitted to take any pictures or use them for his own purposes, due to the fear that it could be used against the photographers in some way.

Amongst other experiences Dinh encountered during his first weeks in Vietnam, this incident proved to him the distrust people had towards Viet Kieus2. This feeling of being a foreigner in his place of birth – disoriented and unaware, ironically could be likened to his experience arriving in the United States. Thus, Dinh decided to begin his journey of “re-learning how to be Vietnamese”, which eventually laid the seed for his permanent stay in Vietnam.

In the early 1990s, although the Vietnam War had ended, its legacy continued through the presence of Agent Orange, as seen in people with deformities on the streets of Saigon. The government and society at large, however, treated it as a taboo subject.

Thinking about how such a horrific issue could be translated into the context of a post-Doi Moi society eagerly trying to turn the page of war, for his 1998 series Damaged Gene, Dinh approached the owner of a children’s clothing kiosk in a popular shopping mall in downtown District 1 and offered her to take a one-month vacation so he could rent her shop to display his art.3 This entrepreneurial spirit went in line with the transformative power which the period of Doi Moi promised. In opting against the traditional gallery space, Dinh was also able to access the general public – those who went to the mall to find themselves colorful, cute, and cheap products. Damaged Gene was just that – a children’s clothing kiosk with green wool sweaters decorated with flowers and small hearts, schoolgirl dresses laced with purple ribbons and bows. But immediately, one realizes that each sweater has two caps, each dress two collars, and each doll two heads.

In using the famous symbol of Siamese Twins to represent the effects of Agent Orange and merging it with baby clothing and toys, Dinh points out the socially constructed perceptions of purity and impurity, of acceptance and rejection. The open nature of the kiosk setting also allowed for genuine reactions of surprise, confusion, and intrigue. Having no way to justify why these clothing and toys felt so wrong, people could only ask what all of this was supposed to mean. As a result, Dinh was able to have many conversations with strangers, allowing for their interactions to serve as a replacement for the typical artist statement often seen in galleries or museums. As a temporary public art project, Damaged Gene welcomes unawareness and disorientation, creating a space for meaningful conversations on issues that often go un-discussed in society.

In parallel to challenging societal attitudes within his local Saigon community, Dinh became interested in exploring America’s post-war portrayal of the Vietnam war.

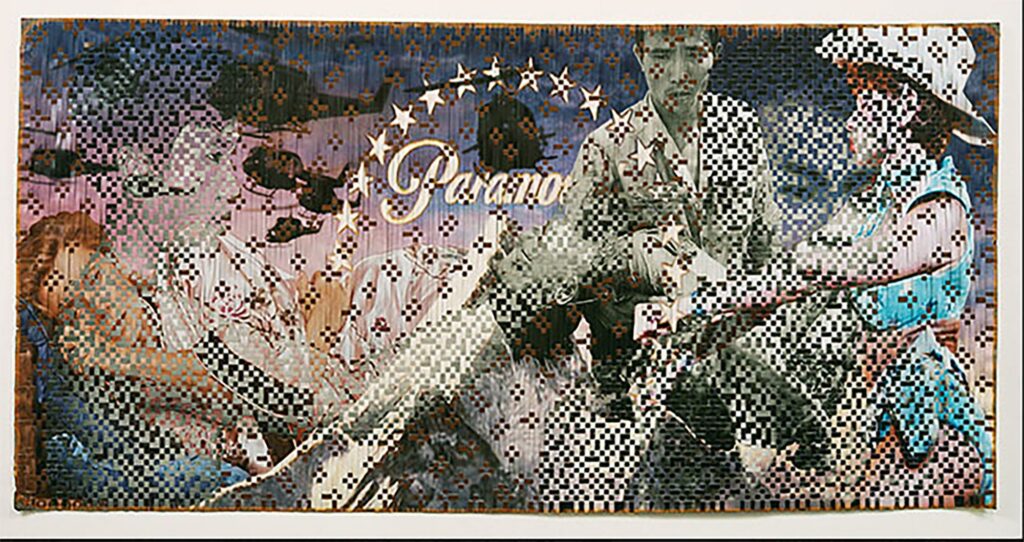

In the general view of the war, there are often two types of images. The first type is the documentary footage in the black and white films of Malcolm Browne, Nick Ut, and Eddie Addams.4 The second type is everything that Hollywood made thereafter. Platoon, Deer Hunter, or Born on the Fourth of July — these are stories of self-affliction and discovery, of alcoholism and prostitution, exploring the wonders of Indochina and the almost-impossible return to America, and ever so often about the war itself. So even those who did not live through the war may feel that they have memories of it. But as more images are woven into people’s minds, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish fact from fiction.

In his 2000 series From Vietnam to Hollywood, Dinh employs the technique of weaving straw mats to reveal the fantasy world that has been imbued in our perceptions. In some of his large-scale photographic weavings, famous Hollywood film studios, such as Paramount, Columbia, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, make up the background, while characters from both war movies and documentaries appear in the foreground, each seemingly ‘trapped’ in their own time and space. The contrasting images and explosion of interwoven colors make it difficult to distinguish which character comes from a movie and which comes from a documentary, who the bad guy and the good guy is. Within these dramatic scenes, Dinh discreetly integrates the third side of the story by including vernacular photographs of Vietnamese people of that time period. He weaves these characters as if they are in the process of disappearing from the image; the clarity with which they appear can therefore be viewed as the amount of ‘screen time’ they would get in history. As an attempt on Dinh’s part to reclaim his memory, the series in fact fully accepts reality’s defeat against Hollywood, where cinematic beauty and romantic despair will always be more interesting to believe in.

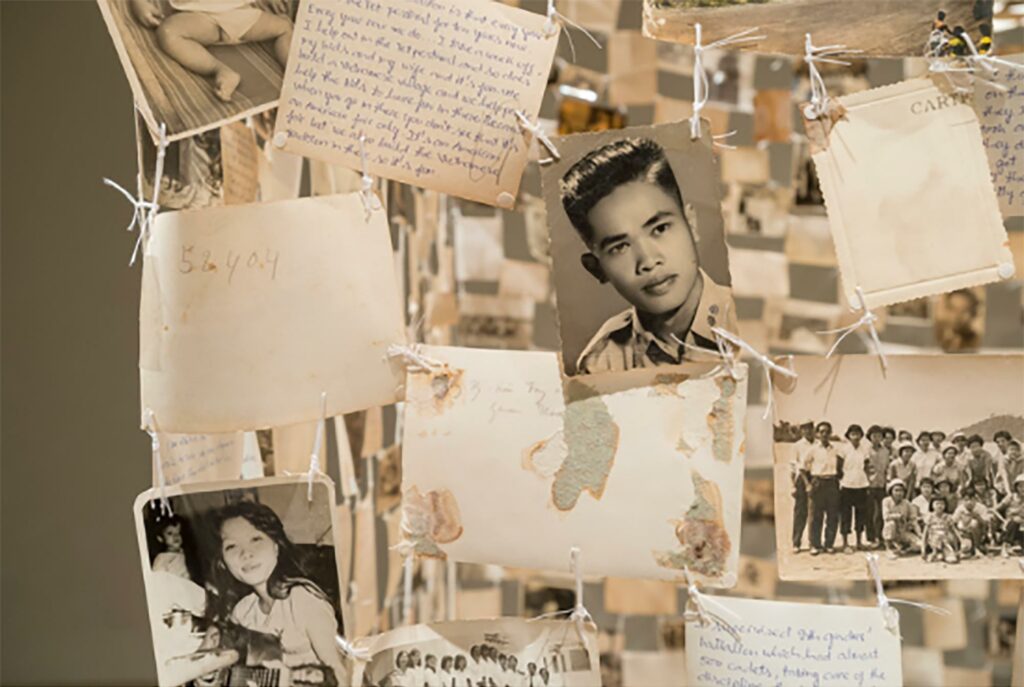

The inclusion of vernacular photographs seen in From Vietnam to Hollywood presents the question of how memories of others can be addressed in art. For Dinh, the answer came through collecting and living with these photographs over many years, until he could develop a form to adequately present them. Crossing the Farther Shore (2016) illustrates Vietnam’s Southern life from the 1940s to the 1980s — from weddings, beach trips, and family reunions, to newborn pictures and individual portraits. These snapshots depict moments of pure bliss, the sweet memories that people wanted to remember. The more images he found, the closer Dinh was brought to his own childhood memories. At the Songkhla refugee camp in Thailand where Dinh and his family stayed for a year in 1978, he remembers the clusters of mosquito nets that formed every night. Under the mosquito net, he could feel protected in the presence of his memories.

This structure also reminds Dinh of the Minimalism movement that was happening at around the same time. While people were protesting on the streets, the works of Donald Judd and Frank Stella seemed like a complete disregard for the war. But the anti-subjective, anti-traditional and symmetrical nature of the movement can also be understood as a silent protest that lays the foundation for starting anew.5

These two parallel stories inspired Dinh to assemble 180 kilograms of found photographs into minimalist rectangular structures, made up of rows after rows of stringed images facing inwards and outwards, allowing the viewer from both sides to see the fronts as well as the backs containing real notes, excerpts from interviews, or passages from the Tale of Kieu by Nguyễn Du.6 From the outside, the work is a tapestry of memory for people to learn from, image by image.7 But on the inside, it becomes an intimate, safe, and collective place for the images to converse with each other. A delicate structure that holds the memories of a time of unprecedented conflict, Crossing the Farther Shore also carries the complex emotional weight of those who had to leave behind their belongings, photographs, and even close ones as they fled. Dinh has no way of knowing who each photograph belongs to, and he will most likely not find his own childhood pictures amongst the piles as he may have liked to, but he considers these lost images to be a sort of surrogate family to him. Thus, Crossing the Farther Shore, which was originally exhibited in Houston, becomes a way for Dinh to share the stories and histories of this extended ‘family’, not only with other Vietnamese Americans but also with the world.

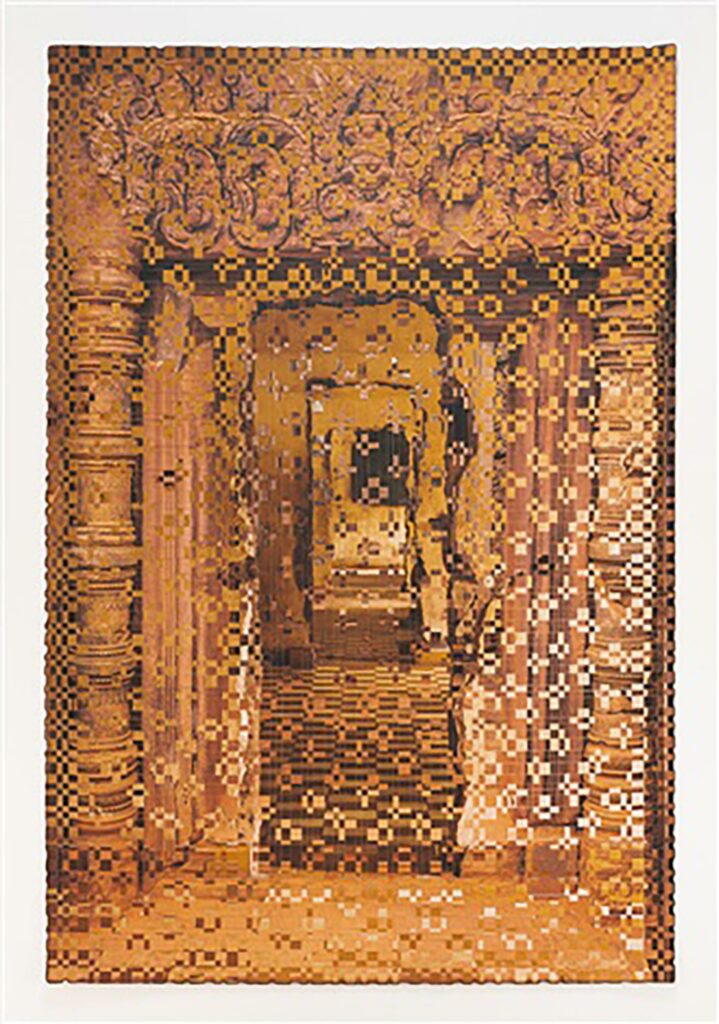

Another crucial area of exploration for Dinh is his connection with both Vietnamese and Cambodian history. Dinh was born in 1968 in Ha Tien, a town next to the Cambodian border, which from 1967 to 1979 was caught in the middle of two conflicts. In 1977, The Khmer Rouge invaded his hometown, forcing his family to flee the country. So naturally, when Dinh returned to Vietnam in 1993, he also visited Cambodia. At the time, the only two sites for tourists to visit were Angkor Wat and Tuol Sleng, where the best and worst of humanity are exemplified in breathtaking capability. This immediately inspired Dinh’s series Cambodia: Splendor and Darkness which interlaces images of prisoners at Tuol Sleng with stylistic motifs of Angkor Wat.

Almost 30 years later, his series Monuments and Memorials still attempts to recreate Dinh’s feeling of visiting these two sites for the first time, but with a heightened focus on the role of architectural commemoration. His signature technique of interlacing vertical and horizontal strips merges the ‘bones’ – Tuol Sleng’s interior, with the ‘skin’ – Angkor Wat’s exterior, creating an optical illusion that brings to the front the meditative amber tone of both sites.8 Depending on the eyes of the viewer, Tuol Sleng may be transformed into a beautifully decorated palace and Angkor Wat into an interior of consecutive broken doorways. There exists a balance of power in the constant silent battle between these sites. This effect is reflective of Dinh’s intention to speak about our tendency to build monuments over memorials. Monuments confer dominance over space and present “an aesthetic value as well as a political function.”9 They are erected to celebrate a hero or an act of victory. But with every demonstration of victory, there is inevitable loss buried underneath. In the process of building over, alternative perspectives become inaccessible to our larger understanding of a time period overshadowed by biographies of greatness. This may just be the case of Angkor Wat’s dichotomy of victory and loss. In deconstructing and ‘de-monumentalizing’ the iconic monument of Angkor Wat, Dinh is viewing monuments as memorials of every country’s larger history.

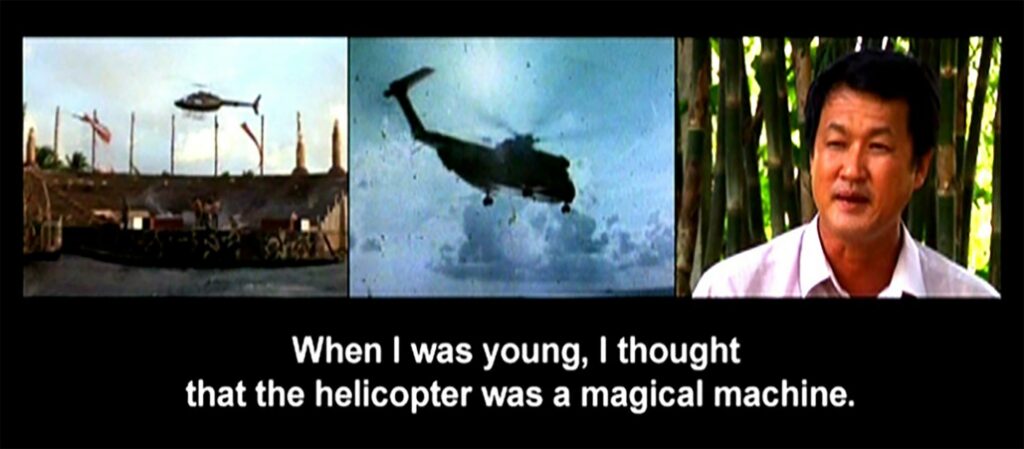

Simultaneously embedded in his artistic journey are Dinh’s collaborative installations and video art projects. The Farmers and The Helicopters (2006) documents the process of a self-taught mechanic and a farmer making a helicopter, alongside a 3-channel video that discusses what this symbol of war means to them in the context of present-day Vietnam.10 Here, art is not only physically made by others but also through the power of their own circumstance that builds relevance to the exploration. Another significant instance was Dinh’s decision to collaborate with Vietnamese war artists for the quinquennial documenta 13.11 Seeing side by side a collection of their war sketches and a short documentary of the artists recounting their experiences, one can comprehend the emotional connection that these sketches are imbued with — hence giving a voice to both the soldiers and the artists.12 Similar to Crossing the Farther Shore, here, Dinh is working with found objects that involve the stories and histories of others.

As explained by art critic Iwona Blazwick, “the found object is distinct from the ready-made in that it is for the most part unique.”13 Dinh’s creation of art through these found objects is a way to give them a home. Because the particular stories he uncovers do not fit into normative history, he uses art’s ability to give objects a universal value, allowing them to be collectively preserved by art institutions. Here, they will be treated, displayed, shared, and studied about as archival records for the future, instead of sitting in Dinh’s personal collection and eventually returning back to the junk shops of Saigon. The project for documenta 13 indirectly addresses the research project of Vietnamese war photographers that led Dinh back to Vietnam 30 years prior. Thus, all of Dinh’s art projects can be seen as collaborations that have brought him closer to his initial goal, of finding and learning about the other side of history.

Dinh Q. Lê’s work reveals a trait inherent to his character – of working on the things that bother him until they feel resolved inside. This is why he has returned to many of his projects that have now become long-term. It began as a process of re-learning all that didn’t make him Vietnamese, which then became a never-ending journey of learning all that does make him Vietnamese. As he explained in an interview with curator Zoe Butt, “If you know history, you own it. An individual with no knowledge of his or her history is an individual without an identity.”14 His journey of collecting, researching, interviewing, and taking photographs, is a way to live with history as it slowly unveils itself to him. Perhaps most significant, is how this learning process has allowed him to show that war is not the only thing inherent to Vietnamese culture. By exploring the layers of complexity and beauty in the stories of others, he sees the value of his own identity. As seen in his Cambodia projects, Dinh perhaps approaches his work best as a half-outsider stuck between the middle of two histories. So close yet so far away, it is exactly this in-betweenness that has given him the space to learn and adapt to the different circumstances life brings.

- Also known as the Vietnamese Independence League, or Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội, it was the Northern organization led by Hồ Chí Minh during the 1st and 2nd Indochina War.

- Vietnamese term that refers to all Vietnamese who have left their homeland to live in another country. There are approximately 5 million overseas Vietnamese, the largest community of whom live in the United States.

- “Agent Orange Aftermath – Artist Dinh Q. Le – Vietnam: The Secret Agent.” Human Arts Association, 2011. www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKjsx8NxIyE. Accessed 12 May 2022.

- The three names mentioned are American photojournalists famous for singular photographs that largely characterized the outlook on the Second Indochina War to the rest of the world. These photographs include “Saigon Execution”(1968), “Thích Quảng Đức Self-immolation” (1963), and the image famously recognized for the “Napalm Girl” (1972).

- Israel, Matthew. “Dan Flavin’s ‘Monument’ / Can Minimalism Protest a War?” HuffPost, 12 Nov. 2012, www.huffpost.com/entry/dan-flavin-and-can-minima_b_6139966.

- Considered the most famous poem in Vietnamese literature. It expresses the determination to endure, and thereby to master even the cruelest destiny.

- “Dinh Q. Lê – Crossing the Farther Shore.” Rice Gallery, www.ricegal- lery.org/dinh-q-le.

- “Artist Dinh Q. Lê and Curator Rory Padeken, in Conversation.” Elizabeth Leach Gallery, 6 Aug. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=UtKVVnhk87c.

- Bellentani, Federico, and Mario Panico. The Meanings of Monuments and Memorials: Toward a Semiotic Approach. 2016, orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/e- print/96405/1/Bellentani_Panico_The%20meanings%20of%20monuments.pdf.

- Starke, Cara, and Stephanie Weber. “A Different Kind of Helicopter: Projects 93: Dinh Q Le.” Moma, 18 Oct. 2010, www.moma.org/explore/in- side_out/2010/10/18/a-different-kind-of-helicopter-projects-93-dinh-q-le/.

- “Light and Belief: Sketches of Life from the Vietnam War.” Fine Art Biblio, 10 May 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=bss-uuqTuX8.

- Taylor, Nora A. “Re-authoring Images of the Vietnam War: Dinh Q Le?’s ‘Light and Belief’ Installation at DOCUMENTA (13) and the Role of the Artist as Historian.” SOAS University of London, vol. 25, no. 1, 2017, pp. 47-61. South East Asia Research.

- Blazwick, Iwona. “The Found Object”, in Cornelia Parker, 2013.

- Butt, Zoe. “Dinh Q.Lê in conversation with Zoe Butt”. Guggenheim UBG Global Map Initiative, 22 January 2013. https://www.guggen- heim.org/blogs/map/dinh-q-le-in-conversation-with-zoe- but.