THIS ARTICLE IS SUPPORTED BY THE BRITISH COUNCIL AS PART OF THE UK/VIET NAM SEASON 2023

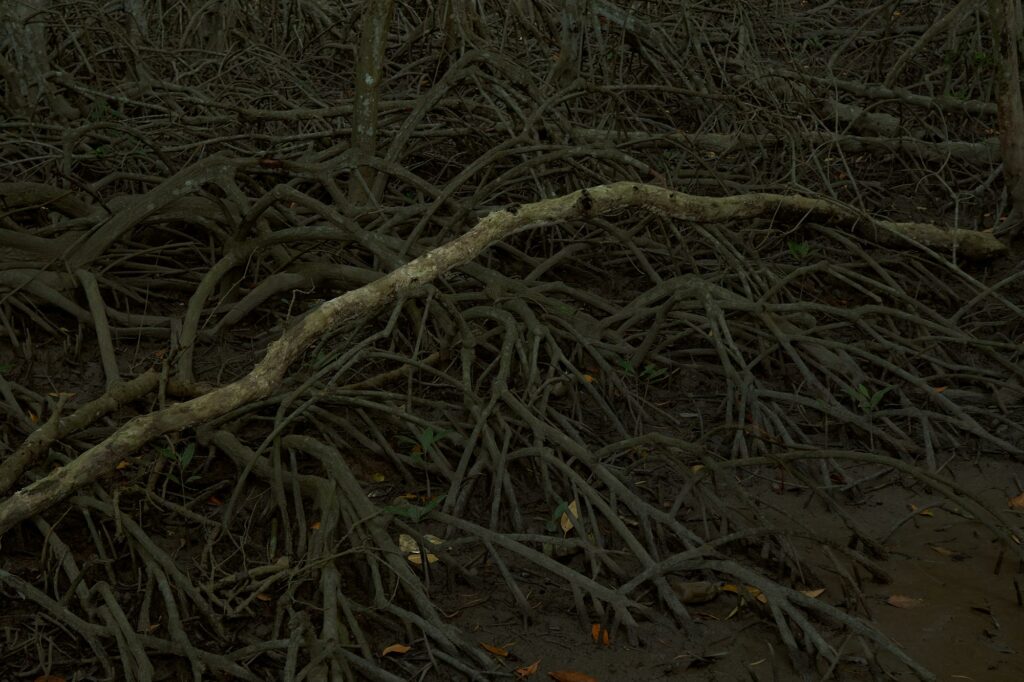

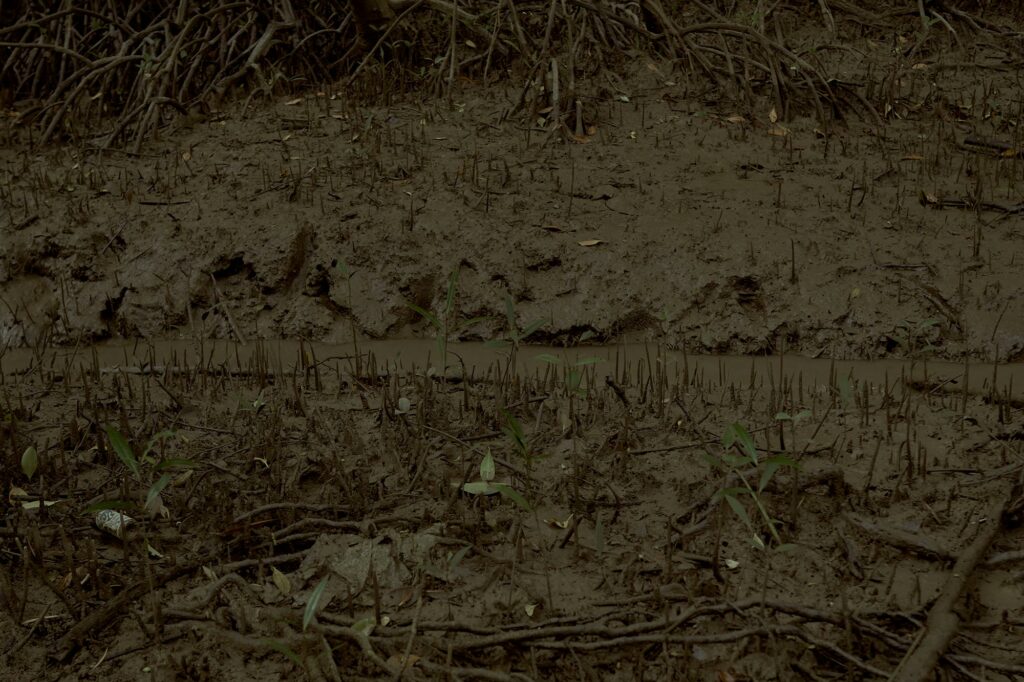

The mangrove (Rhizophora) dwells in an in-between space, where freshwater river currents meet the saline tides of the ocean. When the tide is low, you might notice the spikes emerging from the brown mud, pneumatophores, or aerial roots, that allow the mangrove to breathe even while submerged. You might hear the scurry of feet as crabs burrow into holes that disappear as soon as they become visible. Only then, when the tide is low, can you observe the intricate network of stilts that hold the mangrove tree afloat, roots intertwined within one another so densely that you cannot parse beginning from end. This complex root system constitutes a sophisticated mechanism for staying afloat amidst daily changing tides and becomes a haven for flora and fauna, secrets and histories.

~

It is low tide when I arrive at the Can Gio Biosphere Reserve. Underneath the bridge that leads into the forest trails, there is almost no trace of water, as if it has been absorbed by the plump and glistening mud. As I cross into the mangrove forest, past a restaurant emptied of people and food and onto a concrete trail, the air shifts into the dense atmosphere of swamp. Click. Drop. Pop. Instinctively, I look over my shoulder only to find an empty trail, there is no one on the path. Yet the exposed roots of the mangroves create an effect: the path seems to narrow and the legs of the trees, myriad and plenty, seem to be crawling, closing in on my presence. The trees are curious, defensive, almost hostile.

These observations remind me of similar depictions of mangrove forests in literature. Speaking about the mangroves in the Sundarbans along the eastern border of India and Bangladesh, Indian writer Amitav Ghosh writes in The Hungry Tide,

Visibility is short and the air still and fetid. At no moment can human beings have any doubt of the terrain’s hostility to their presence, of its cunning and resourcefulness, of its determination to destroy or expel them. Every year, dozens of people perish in the embrace of that dense foliage, killed by tigers, snakes and crocodiles…There is no prettiness here to invite the stranger in: yet to the world at large this archipelago is known as the Sundarbans, which means “the beautiful forest.” There are some who believe the word to be derived from the name of a common species of mangrove — the sundari tree, Heriteria minor.1

Caribbean writer Maryse Condé writes about her island of Guadeloupe, a department of France, in Crossing the Mangroves, and draws upon a similar refrain, “You don’t cross a mangrove. You’d spike yourself on the roots of the mangrove trees. You’d be sucked down and suffocated by the brackish mud.”2

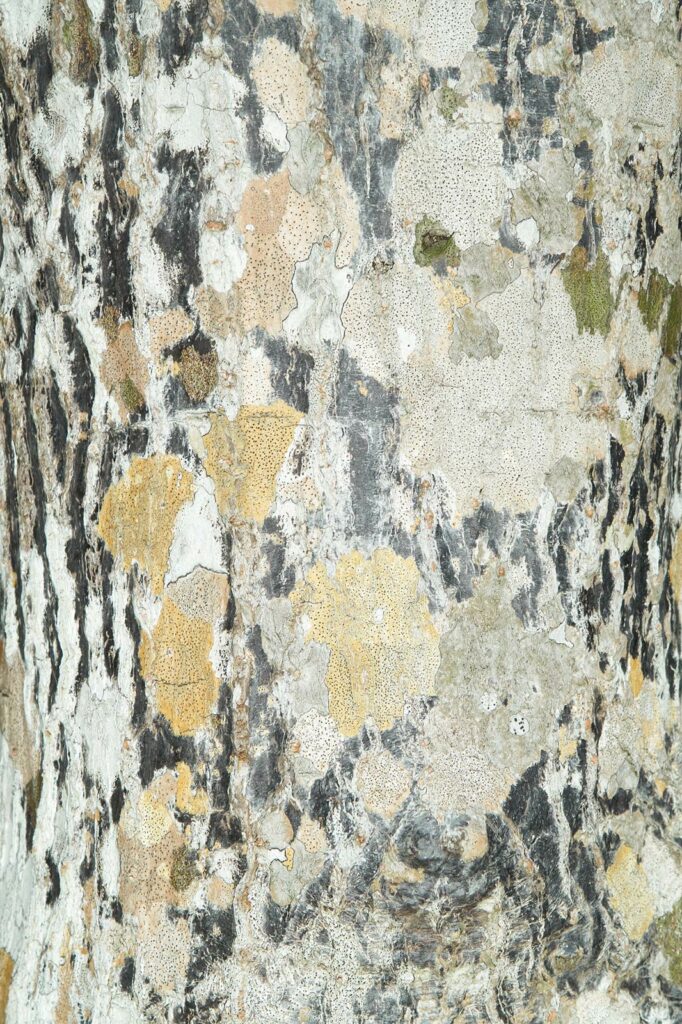

Perhaps it is not just an optical illusion; the mangrove forest is indeed on guard when it comes to greeting its human visitors. This nature, wary and reluctant, resembles our own adjustments in new situations and encountering new people. Like us, the trees know better than to immediately embrace the strange Other, they are always observing. Only slowly do they beckon and reveal, and once they share, it is an endless flow of giving.

How is it that these images of the mangroves, taken from three different places – off the Bengal coast of India, in the archipelagos of the Caribbean, and along the waterways of the Mekong Delta –demonstrate a similar reluctance to hospitality? It is as if there is a shared history they withhold, only revealed to the curious visitor, whose patience will be rewarded with stories only told on their terms, not ours. Those terms are dependent on forces beyond our control, like the gravitational pull of the sun and the moon as it manifests in the ebb and flow of the tide. At unpredictable times of the day, the tide will recede to expose the rhizomatic root system of the mangrove and its storied past. Only then might we see something beyond the surface, something that is often hidden by the water. What is that past, how is it related to the surrounding geography and how might it inform the way we think about relationality today?

In the Mekong Delta alone, there are many layers to that past. The region, for example, has seen numerous civilizations, beginning with the Khmer and Champa up until the 19th century, with overlapping instances of what scholars today might call Vietnamese southward expansion or “nam tien.” After only a short period of Vietnamese settlement came the arrival of the French in the 1860s. These Mekong waterways were declared by French governor-general Pierre Pasquier in 1930 as “rich patchworks,” filled with “golds and emeralds as far as the eyes could see”3. It of course didn’t take a foreigner like Pasquier to recognize the delta’s potential for agricultural development and trade. And more recently, while the Americans were not official settlers of the region, they left key vestiges that would endure decades after their departure. Their bombs and defoliants would eliminate almost all of the vegetation and wildlife in the area in the 1970s, and remains seeped into the land to this very day.

This record of empires is deeply embedded in the land and vegetation of the delta. We might even say it is this rich, sedimented history that has nourished the mangroves back to health in the wake of war and conflict. Atop the watchtower at Can Gio, where dense treetops abound, I was surprised to learn how young the trees that populate the Reserve are. Many of them are no more than two to three decades old. This is because in 1978, the HCMC Forest Department initiated a vast effort to repopulate the forest in the wake of American defoliants and bombs. This initial rehabilitation was to respond to a demand for construction raw materials and fuel wood. Then in 1991, the status of forest management shifted from an economic standpoint to one of protection, where thinning and poaching of forest trees would be prohibited altogether by 19994.

The uniformity across species and age of the trees served as both the forest’s strength and weakness. While this characteristic meant that the herbicides affected the forest in a uniform manner, it also made repopulation easy and widespread. Unlike many other kinds of forests, the mangrove forest can repopulate within just a decade or two.

The mangroves in other places are keepers of similar histories of empire. On the Indian subcontinent, Britain was not the only European presence in the region. Aside from the history of British rule (1757-1937), the area around the Sundarbans and Kolkata also saw Dutch and Danish posts, Portuguese factories and French settlements.

As for the archipelagos of the Caribbean, sometimes also known as the West Indies, varieties of Spanish and French creole are linguistic testaments to the confluence of European encounters with Africa and Asia. For creole, there are no singular etymological roots to which one can trace the language. As a predominantly oral language, it has multiple versions that continue to change through the generations. Rather than theorize the source of language or identity based on the idea of root, which privileges the tracing of a single origin, Caribbean thinkers like Patrick Chamoiseau suggest instead the image of mangrove. This epistemological shift prompts us to be less concerned with essence or purity, but to hybridity and relationality, to consider the multivalent parts of who we are.

Indeed the confluence of oceanic and river waters in such regions points to a shared colonial past, of competition between cultures as well as between nature and human society. But just like how the mangrove forest’s shared characteristics can be both its weakness and its strength, can we imagine a similar reframing, in which these intricate histories of empire and competition also provide a model of interconnectivity? What is beyond the shared colonial past that binds us? Can we perhaps channel what Chamoiseau and his peers call a “mangrove of potentialities (une mangrove de virtualités)”5?

We are thus called to shift our epistemological or knowledge-making processes, to use the mangrove as an example. We might thrive based on similarity, but our real strength is our ability to remember and think ecologically, globally. To suggest the mangrove as archive is to refer to its store of histories, but also to this modality of existence beyond oneself and one’s history.

Alas this is what the mangroves told me as I sat quietly, waiting, somewhere deep in Reserve, its generosity a deluge no longer withheld.

1. Amitav Ghosh, The Hungry Tide, New York: Mariner Books, 2005, p.7.

2. Maryse Condé. Crossing the Mangrove. Trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Doubleday, 1995, p.158.

3. Quoted in Biggs, David. “Problematic Progress: Reading Environmental and Social Change in the Mekong Delta.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 34, no. 1 (2003): 77–96.

4. Pamela McElwee. Forests are gold: Trees, People, and Environmental Rule in Vietnam. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016.

5. Jean Bernabé, Patrick Chamoiseau, Raphaël Confiant. Éloge de la créolité. Paris: Gallimard, 1989, p.28.