Polaroid, or instant cameras, were first introduced in the late 40s and almost instantaneously gained popularity. From family to professional artists, everybody loved the instant image: its convenience, its washed-out palette, and most of all, its fascinating experience. It was magic fitting in your palm, transforming the often long and painstaking photographic process to but a few seconds of waiting. When the digital age came with the ubiquitous camera phone, it took away Polaroid’s unique selling point and predicted the death of the Polaroid corporation. But instant film proved to be resilient. In 2015, Fuji’s Instax instant film was the bestselling item in Amazon’s Camera category, outnumbering its digital counterparts. As a matter of fact, it inspired today’s ever-growing photography community Instagram.

Before digital, polaroid cameras were used like our present-day smartphones: to snap daily moments for the sake of keeping memory. Thus, it’s not easy to explain why we still have a soft spot for instant films while the much more convenient and inexpensive option of our phone is available. Is it just another fashionable retro trend? The inimitable look of soft hues worth the hefty bill? Or perhaps it’s seeing colors and forms emerging in a quiet rectangle, the sad and beautiful experience of witnessing the gone moment materialized before our eyes, offering the consolation that when time passes we can still keep its physical evidence. The human need to record life and perhaps stop time has a long history, proving even more essential in modern hectic pace.

Now back to the game with the most popular product being the funky looking Fuji Instax Mini 8, the instant camera is often associated with selfies and party photos, generally images taken at fun times. It could be said that due to the distinctive haphazardness, smeary quality and subdued tone, instant films are made to celebrate the intimate banality of daily life rather than undertaking a serious project. But such very characteristics, often seen as limitations, contain untapped artistic possibilities.

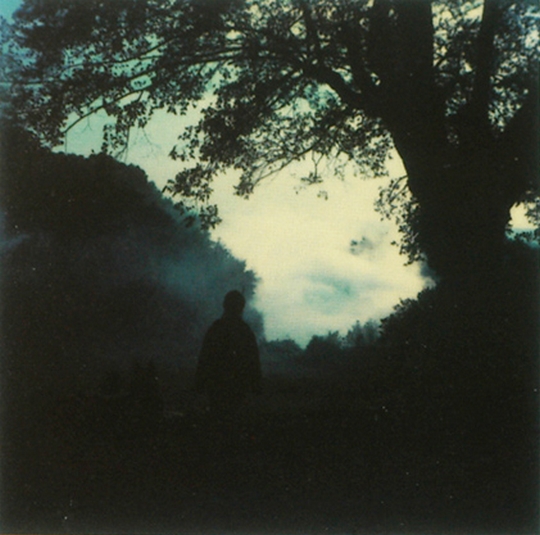

Andrei Tarkovsky, the iconic Soviet filmmaker known for long and leisurely takes, made use of these quick Polaroid shots to snap brief moments from the incessant flow of time. His images were dreamlike and poetic although they portrayed common sights and people, leaving the melancholy of seeing things for the last time as they were. He shot diaristic pictures of how light arrived on his flower vase, the ephemeral morning fog in his native Russia, the loving presence of his wife and dog among other things. They were there, the conjured atmosphere feels almost tactile, and yet the images seem like a fond farewell. Life was happening unhurried and the landscape was still, but time unstoppable. Tarkovsky was particularly preoccupied with the concept of time, describing it as “not just a neutral, light medium within which things happen. We feel the density of time itself”. These still images are beautiful in their own right, yet we find in them traces of his philosophy of projecting time as a tangible element in his moving image works. The blue-ish hue of the film he used add to the nostalgia and a sense of mystery, reflecting his what has been said about his cinematic works that ‘capture life as a reflection, life as a dream’.

The fact that a film can transform into an image by itself used to be an almost unimaginable phenomenon – thanks to the quick developing chemicals inside the film, the process happens in just a few seconds without effort. The immediate availability and physicality of the image were ideal for documenting fleeting encounters with vagabond kids that hop from one train to another, as Mike Brodie did in his series Tones of Dirt and Bone. Back in 2004, Brodie was 17 when he decided to travel cross country by illegally train hopping. Along the way he picked up a SX-17 somewhere and started immortalizing those he met, earning the title ‘Polaroid kidd’. Instant films was the perfect tool as they made it possible for him to share the images with his fellows and may be even hand them out as a gift, as he knew too well that rendezvous isn’t common for those homeless by choice. In fact, years later in an interview, Brodie admitted being out of touch with most people he had photographed.

The costly film came in only ten sheets each box and discontinued only more than a year later, forcing Brodie to stop this project and moved to 35mm. But because there were a limited number, each image / moment captured felt precious and deliberate. The condensed edition of the book tells a young man’s sense of adventures, serendipitous meetings and the rough side of life on the go in two intense years. But as sudden as how he started taking these photographs and train hopping, Brodie compulsively stopped one day. He never thought of picking up a camera again, as he tried to get out of his nomadic lifestyle and integrate into society.

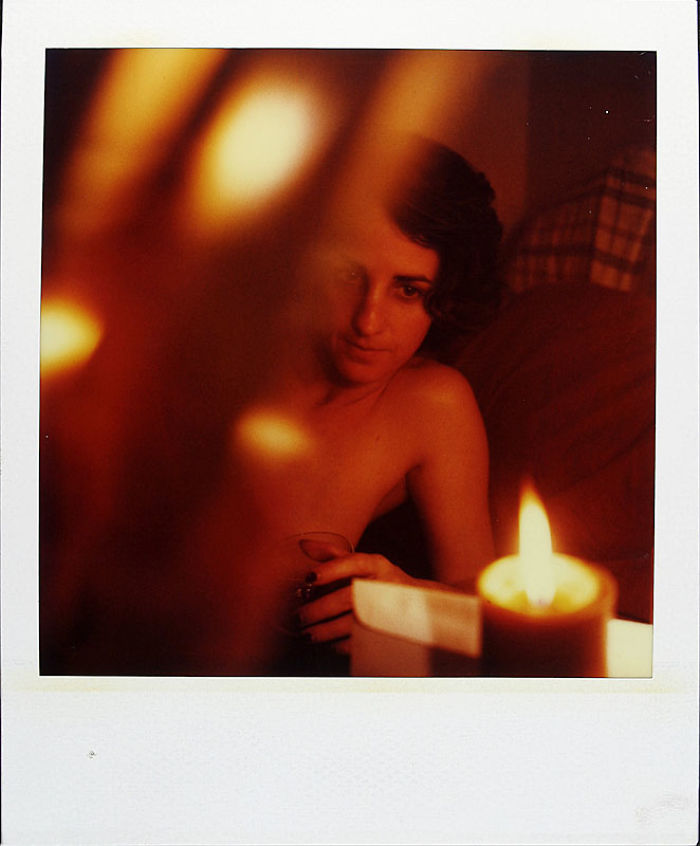

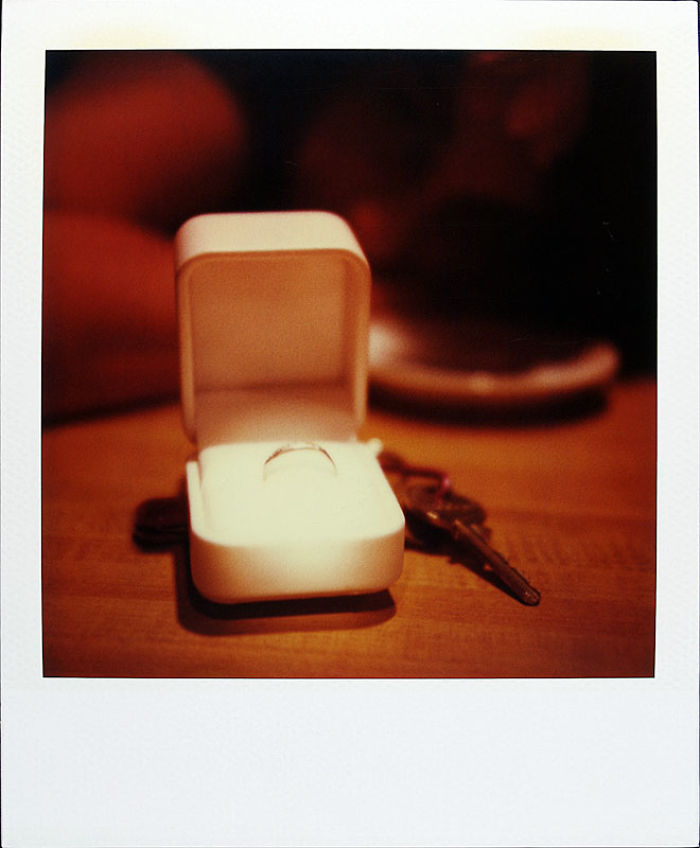

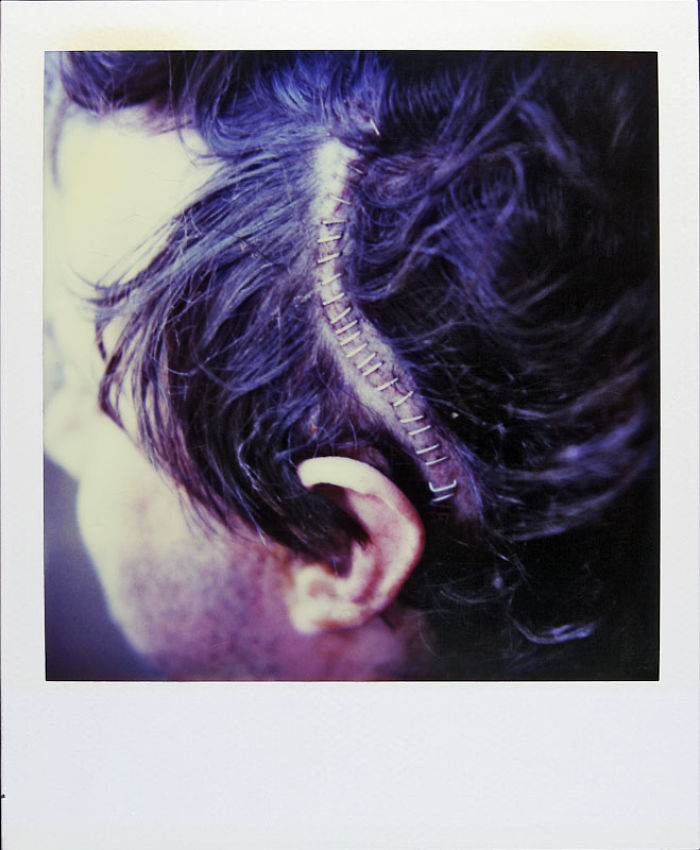

Like Mike Brodie, the late photographer Jamie Livingston used the SX-70 to document his journey – but instead of wandering aimlessly, he knew where he was heading. Livingston started taking one Polaroid picture per day when he was a student, and continued the project titled “Photo of the day” after he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. On October 25, 1997 when Livingston shed his last breath, 6,697 polaroids remain from a 18-year project. The physical exhibition organized by his close friend opened at Bard College where Livingston started the series included digital reproduction of every Polaroid and took up a nearly 90 m2 space. The collection, dated in sequence and of big scale, told the linear story of one man’s life and death. He recorded everything: food, friends, girlfriend and later wife, cityscape, himself when happy and sick, the ordinary moments and the milestones. The photos standing alone don’t have much meaning but when put together, they took a life of their own. One of his friends has spoken about the collection that “When I look at a picture that I was involved in or know about, you’re just sent right back in time and you just remember everything about that day.” The stories of Livingston and Brodie, who used the medium to record their numbered days and then stopped picking up the camera altogether, left a poignant yet true statement about the use of photography as a safe deposit box to preserve memories: Without the person, the smell, the laughter, meanings slip those two dimensional images.

Not enlargements or framed photos hung on the wall, instant films only offer the humble palm-sized print and not the convenience of reproduction. As photographers nowadays aim for the big pixel, the intimacy and singularity of instant films can be an old-fashioned yet refreshing artistic choice. The stories told by this medium have been quite heavy, but it doesn’t mean that we can’t use instant film to do something fun or to commemorate our special days.

When introducing Hawkeye, his then 4-year-old son to photography, Nat Geo photographer Aaron Huey did not think of an iPhone. On their first big trip together, Huey gave Hawkeye an analog camera like those he himself used in his younger years. He chose an instant camera partly out of nostalgia for film and the scarcity of physical images today, but also because he didn’t want to see a kid learn about making photographs by snapping constantly on a digital device. He wanted the process to be slow, each frame to mean something, a photograph to be an object that could be held in his hand and stored in a shoebox. The use of photography to keep memory is foreign to Hawkeye as he explores each day with inexhaustible energy. To the toddler untouched by the past and standardized aesthetics, taking photos is synonymous with interaction with people, their smiles and conversations. Not all of Hawkeye’s images are perfect: some are blurry, out of focus, cutting things off, filled with flaws and freedom.

The instant camera is not an uncommon tool for our local photographers: Linh Pham has taken photos of his friend’s wedding with an Instax Mini 90 Neo Classic and 10 rolls of film. Who knows in the future whether these would turn into dear or bitter memories. But to look at, they are cute and memorable wedding pictures, and what else can we say but “Carpe Diem?”