MATCAxC4 JOURNAL: Conversations Around Photography, Vietnam & UK

A series of articles discussing various aspects of image-making. Supported by British Council Vietnam’s Digital Arts Showcasing grant 2021.

????✍️??

Queer people, despite a minority in society, are undeniably part of the social and cultural fabric of Vietnam. They appear in films and mass media, show up in word-of-mouth accounts, or can be encountered in real life. The community has come a long way to earn such visibility in the public sphere; yet, many still find it necessary to self-regulate their behaviors and individual expression in accordance with prevailing social mores.

Photography, a medium marked by instantaneousness and total creative control, offers a possibility for queer image-makers to construct a realm unbounded by societal norms, where the queer condition could then be sincerely illuminated. In an attempt to chart some trajectories and implications of such practices, I reached out to four Vietnamese artists—Mắt Bét, Hoàng-Anh Nguyễn, Nguyễn Quốc Thành, and Kai Nguyễn—in hope of exploring how their photographic images could enrich or redress our understanding of the contemporary queer identities and experiences.

For Mắt Bét, images of her domestic life with her same-sex partner are put on display on her public Instagram account, and more recently as part of the Museum of Heartbreak exhibition (2021) in Ho Chi Minh City. Mắt Bét shot her partner at startling proximity: the sitter appears at no more than an arm’s length from the camera, conjuring up the impression that her calm posture would be unsettled by the slightest perturbations. This quality stands in contrast with Maika Elan’s acclaimed series The Pink Choice (2012), dated almost ten years ago. Although similarly shot in the private setting of the domestic interiors, Maika Elan’s photographs of queer couples maintain a definite distance from the subjects, which is consistent with her position as a mere observer. Mắt Bét erases any such gap. Foregrounded by an established relationship, even when she does not appear in the frame, the photographer’s close proximity with the subject implies their unfettered affection for each other, hinting conspicuously at the couple’s cohabiting domestic space as the necessary backdrop for the images.

In a way, Mắt Bét’s photographs are an invitation for the wider public to experience her delicate and sincere sentiments in a queer relationship, narrated from a first-person perspective. The design of the Museum of Heartbreak exhibition lends support to this claim. After taking a flight of stairs to an elevated platform and walking across a short corridor, viewers are greeted by a veil printed with images of hanging undergarments. Mắt Bét shared that the couple’s intermixed laundry hanging on the balcony partially shields their private life from the exterior gaze of residents in the opposite apartments. Meanwhile, at the exhibition, the translucent pieces of fabric are not partitions but thresholds for viewers to transition from outsiders to guests in the artist’s lived interiors. The semi-open enclosure that houses Mắt Bét’s works then emerges as a cozy corner of a loft. Here, the wall-mounted photographs are printed at a scale that demands viewers to come physically close to the exhibits, analogous to slowly stepping into the couple’s domestic life filled with mundane gestures of love. That viewers are entrusted with such intimate experiences is an indication of Mắt Bét’s faith in the sympathy of these “guests”, that they will walk away from her simulated home more understanding of and sensitive to the presented queer subjectivity.

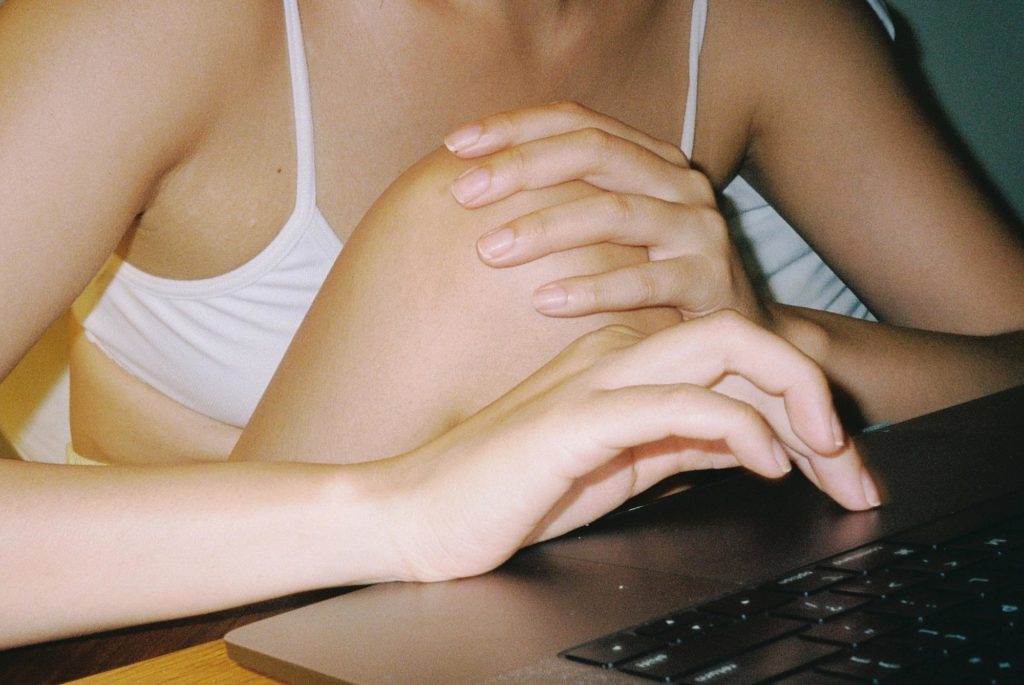

Whereas mingled undergarments are proof of Mắt Bét’s intimate cohabitation with her partner, the chest binder rouses conflicting sentiments for Hoàng-Anh Nguyễn in Gender Bound (2019). On the one hand, it helps boost her confidence by constricting the outward presentation of the body part that she feels embarrassed about as a butch. On the other, wearing a piece of garment that exerts an adverse force on the body is physically onerous and even harmful to the body’s biological functioning. Art becomes a vehicle for Hoàng-Anh Nguyễn to make sense of this antagonism. Performing with the chest binder in front of the camera, the artist gains an opportunity to interrogate her relationship with this everyday yet troubling object. In the first photo, she is seen examining her reflection in the mirror while trying to use the binder to compress her bosom as much as possible. The constricted form of the breasts is reproduced in the second photo, but instead of the binder doing the work, a set of arms of an unidentified woman is hugging tightly to Nguyễn’s chest. The artist’s arms, no longer busy with adjusting the fit of the binder, rest at the ankles of the other person. These shifts in formal composition parallel her own revelations. She disclosed to me that she no longer wanted to endure the pain of wearing the binder, that her partner should still love her regardless of the redeeming effect of this accessory.

Publicly accessible on Nguyễn’s website, images of Gender Bound reveal to passing Internet patrons the private struggles unique to certain queers who trade physical torment for a body image that aligns better with their gender identity. Much deliberation went into deciding on publicly displaying these immensely private moments, exposing both her bare skin but also insecurities about her body image; often cases, these sentiments are kept to oneself or shared only with trusted confidants. For Nguyễn, to present the project openly is, first and foremost, to acknowledge and accept her imperfections as an integral part rather than a shameful element of her current bodily state. Publicly showcasing these images is then a gentle way for Nguyễn to reach out to close and distant family members and friends who might not fully understand the experience of being at odds with one’s biological traits, nor recognise the legitimacy of a gender expression outside the seeming standards of masculinity and femininity. Starting out as a mechanism for Nguyễn to cope with personal trauma, the work culminates with the hope that, as more of such images circulate, people would perhaps start to see gender-nonconforming bodies as less of an aberration and more of a normal fact of life.

That the queer body is not a neutral entity but a site of yearnings and conflicts is also picked up by Nguyễn Quốc Thành. His series Lost Pixels (2016) comprises images taken from digital platforms for gay hookups and visual consumption of homoeroticism, which subsequently had all direct traces of the queer body removed. The images were then printed on transparent decal films and placed against window panes for the Mise-en-scene exhibition by Nhà Sàn Collective, which was at the time located high in the Hanoi Creative City building. Details that can reveal the subjects’ identities are unrecoverable, but the remaining contours still give some clues about the lean builds equipped with narrow waists, developed backs, and curvy buttocks. These allude to certains ideals within the gay communities that prize the toned body as a currency for sexual exchange, as an object of desire and worship.

At the exhibition, depending on the viewer’s perspective and the time of the day, different things can fill up the blank bodies. It could be a clear blue sky that invites sensuous imagination, or patches of residential apartments and street traffic commonplace in the cityscape. The eyes leave the grip of absent bodies and wander off to the photographs’ backgrounds. Simultaneously, city views behind the window panes draw viewers’ attention away from the exhibition space and towards the humdrum urban reality outside.

Nguyễn shared that the erasure of queer bodies is merely a means to opening up ways of seeing that are under normal circumstances easy to miss. Specifically, he proposes that beauty or art could be out there on the streets rather than being confined within a white cube, and that gay men could perhaps measure one another with yardsticks other than the body. Another insight into the queer condition also unfolds with the image processing method. The removal of bodies takes with it the instantly gratifying effect on gays—the original target audience of these images. The mind, once unencumbered by immediate sensory stimulations, finds a unifying thread running across the artifacts. Performing to the camera, the photographed subjects all yearn to be desired; they scramble for the toned, presentable bodies just for a chance at intimacy and love.

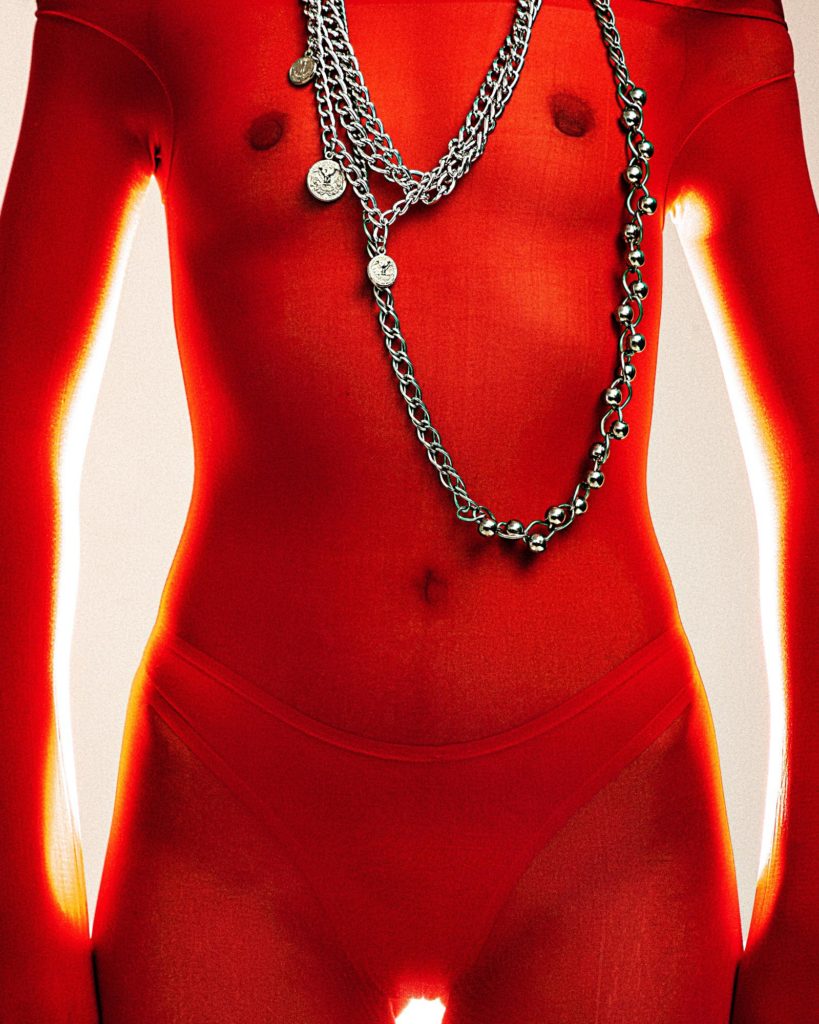

Queer relations need not be seen through the lens of sex and romance. In fact, Kai Nguyễn seeks to place at the center of his practice a kind of closeness that looks past any tendency to sexualize or romanticize the photographer-subject relationship. He sees in his friends a reflection of himself, true to the belief that his identity is shaped for a significant part by the communities that he belongs to. Indeed, his collaborative text-image projects with Phạm Thu Uyên, (On) queerxposure and reflect | tcelfer, feature several subjects, all of whom are his friends. As much as the images demonstrate the subjects’ unique individual expressions, they also reveal the fluctuations in the photographer’s state of mind. Nguyễn confessed, sometimes he feels adrift, sometimes vulnerable, other times compelled to let go of all unbridled feelings. These sentiments echo in flashy images of sitters confidently confronting the camera; they don a variety of attention-grabbing costumes, or hardly anything at all, flaunting the bare, exposed flesh.

The intimate relationship between the self and the photographed subjects, coupled with the lack of any descriptions of involved persons, begs the question: where shall queerness be located in the variegated images? Is it to be found in the photographed subjects or in the photographer, comprising his identity and his frame of seeing, interacting, and photographing his mates? The intentional ambiguity could convey an attempt to destabilise a formulation of queerness rooted in invariant notions of being a particular gender and desires towards certain sexes. Queerness then becomes ephemeral, almost unreal, and constantly changing, through the spontaneous gestures of performing and seeing. Viewers are then free to speculate what makes an image “queer”; is it because that guy appears feminine, this body looks androgynous, or due to the apparent tension between the photographer and model? As it turns out, precisely this act of seeing, laden with subjective presuppositions, is what effectively queers the images.

That photography is a medium capable of transmission at scale and with ease does not necessarily warrant viewers’ access to the many queer identities and experiences as presented here. For many, photography may be simply to serve the personal need to record one’s experiences or for self-therapy. But more than that, queers use photography as a tool to make known their unique lived conditions and struggles that have yet left the blind spot of society. They show up only momentarily, flesh to flesh, naked, entrusting viewers with their fragility and unfulfillment stripped bare through photographs. Are they loving, not just each other but firstly themselves? Are they hurting? Are they all right?