It is an overwhelming experience to go through a life’s work of photographer Lam Duc Hien, attempting to grasp the beauty and tragedy in the world he has captured. War has moved Hien from one place to another, first as a child refugee, now as an unflinching witness.

Among other awards, Hien has won 1st prize in the Portrait category, World Press Photo 2001 with his series “Iraqi People”. His interest in Iraq stretched over 25 years; yet after a narrow escape in Saddam Hussein’s native village, Hien decided to leave the majestic land that requires too many sacrifices. That was when he embarked on a 4,200-km journey tracing the Mekong river from the delta in Vietnam up to its source in Tibet, recalling childhood memories and interpreting the river’s various meanings to inhabitants. The commitment to children’s rights and reporting lives in conflict zones ties his vast bodies of work.

[Lam Duc Hien] My father is Vietnamese and my mother is Laotian. I grew up in Laos. When I went to France, I learnt many languages. Language for me was a way of communication. After two years studying languages, I decided to become an artist. I studied everything: from painting to drawing, photography, video and sculpture. When I was in second year of art school, something happened in history.

In 1990, the old dictator regime in Romania collapsed. I felt like I have to be there. So winter that year, I took the train from France to Italy, arrived in Yugoslavia, took the bus and walked to the border. It was dark, snowy and cold. The guard saw me and was taken aback. A “Chinese” guy out of nowhere in Yugoslavia! I told him I wanted to go to Timisoara. By chance, there was a humanitarian convoy which let me come with them. I stayed with students there. They called it the revolution. They took me everywhere and asked me to take pictures. I saw how they worked so hard despite the cold and the lack of materials.

I spoke about the situation after coming back to school in Lyon. We are spoiled children, we should help people who have nothing but still work hard. We are artists and we should be concerned artists. Artists should not just talk but take actions. Some newspapers came and reported. Eventually, with the support of a French organization, we came back to Romania with paint, paper and art supply.

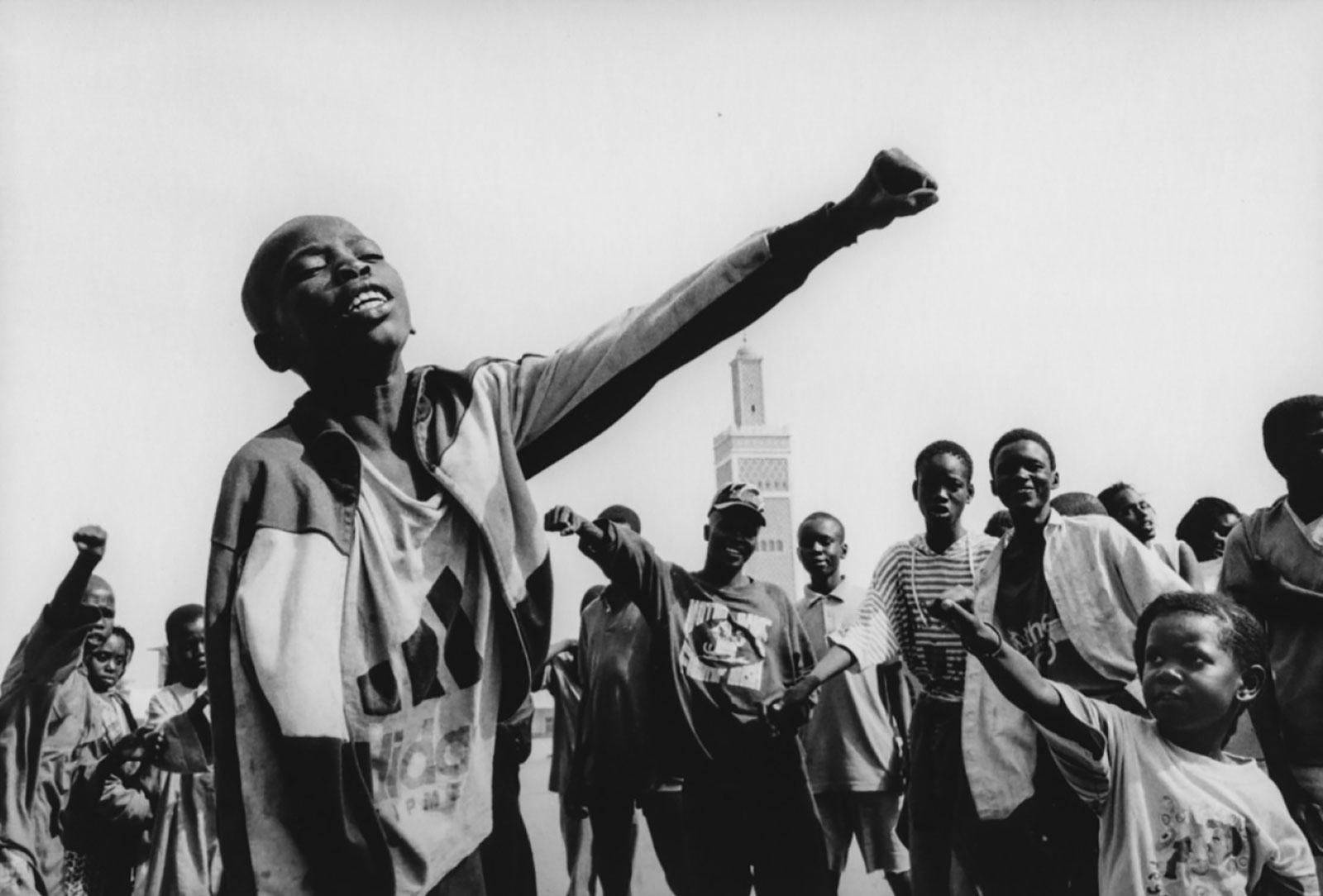

I wanted to not only be a witness but to help. There’s a voice calling me: ” Do something”. In my opinion, artists have to be concerned with politics, with daily life. I’m fighting against the idea of war, injustice, corruption and dictatorship; taking pictures was a way to denounce such situations. I have a lot of anger inside me and have to speak out.

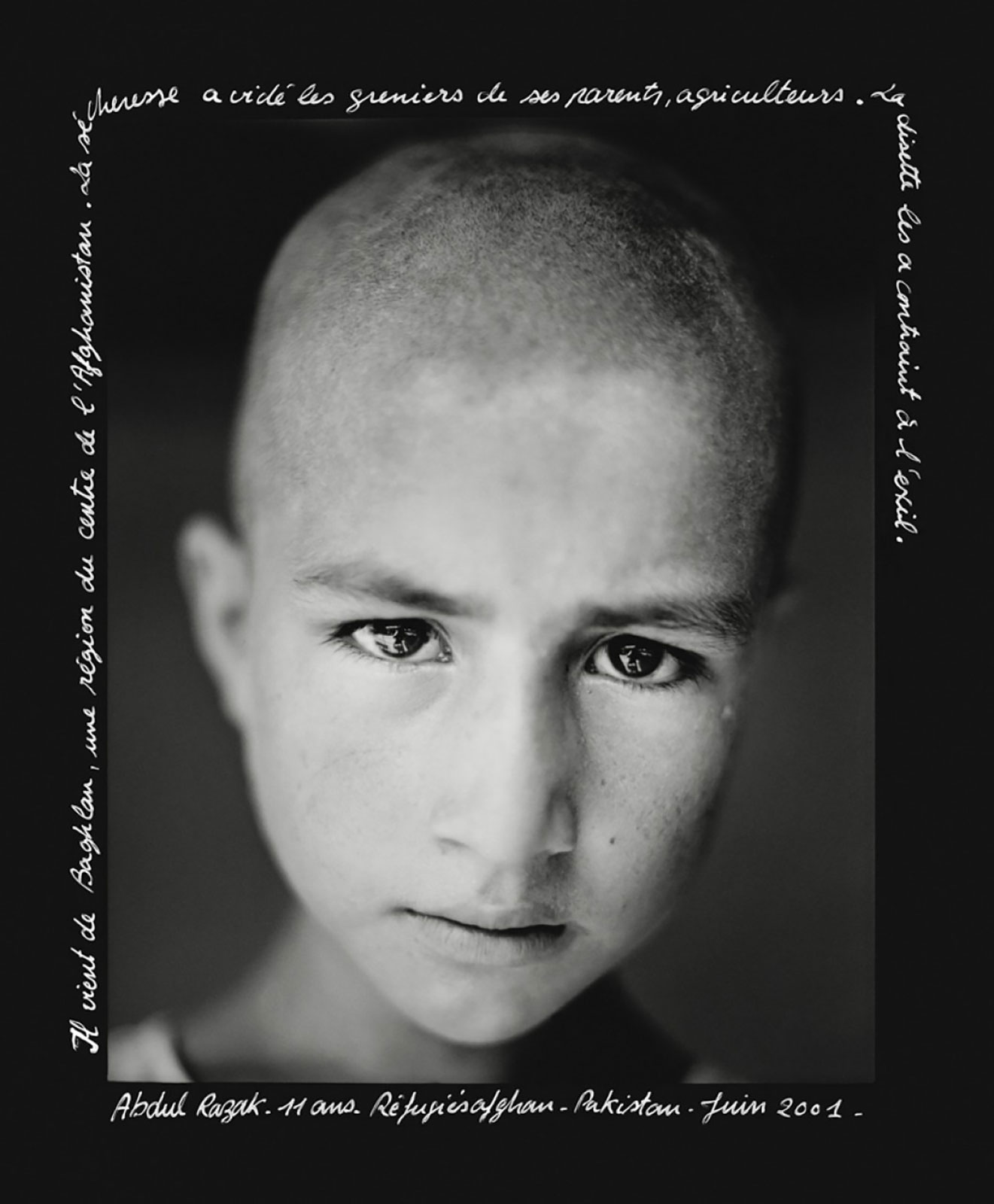

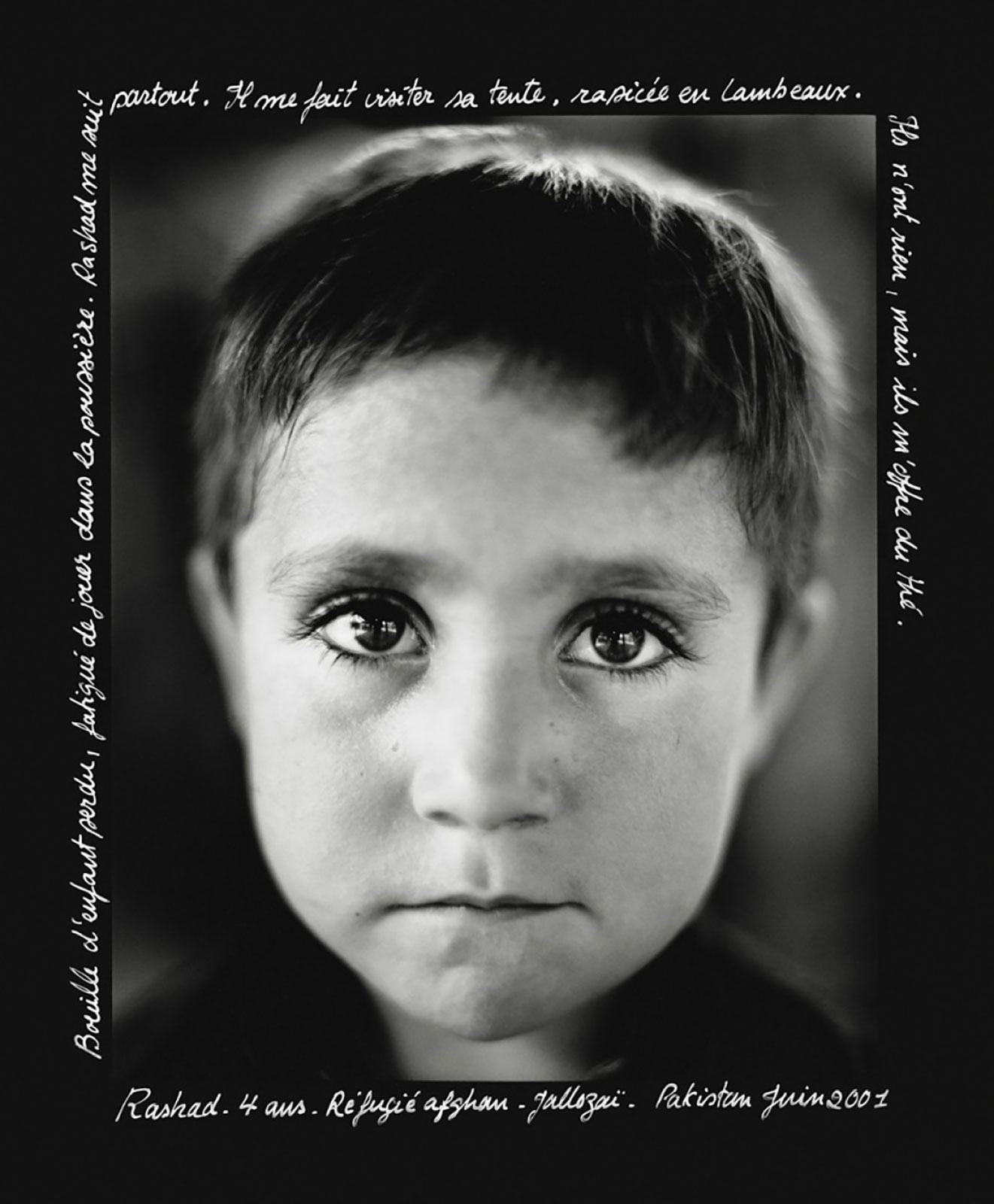

In 1991, I was so concerned about Iraq. They were killing Kurdish people, who had to flee to the mountains. I took pictures of the refugees and was crying because they had to run, it’s cold up high, they didn’t even have a pair shoes while having to walk in the mud. I was just like them, escaping from Laos on a boat, crossing the river by night, then being put in a camp. It’s a very hard life. When I took pictures of these people, I feel like portraying myself 20 years ago.

In 1994, I became a member of Agency VU’. Christian Cajouelle, then the director, understood that each photographer looked at reality with their own eyes. He prioritized the photographer’s own way of looking over the aesthetics.

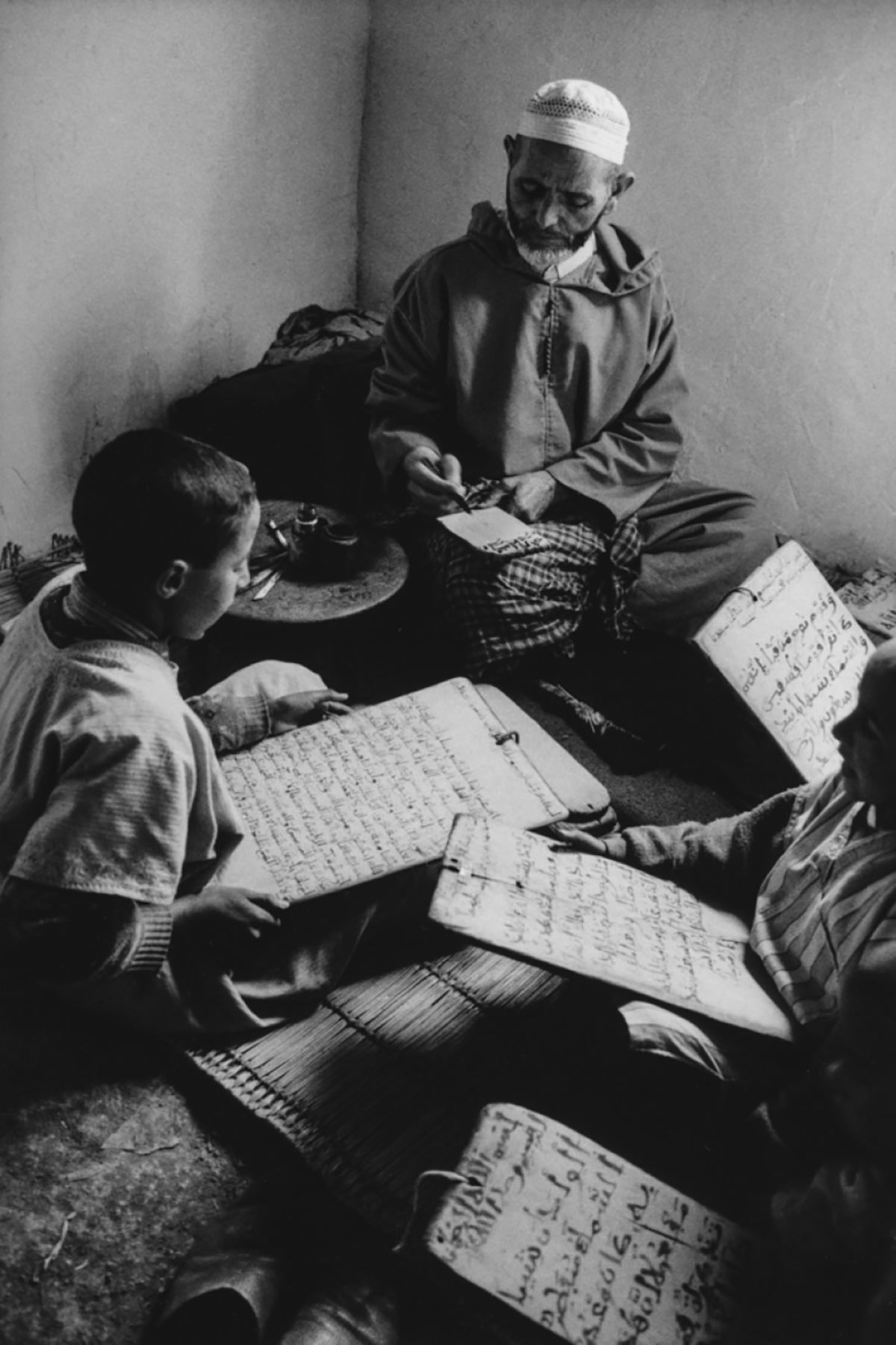

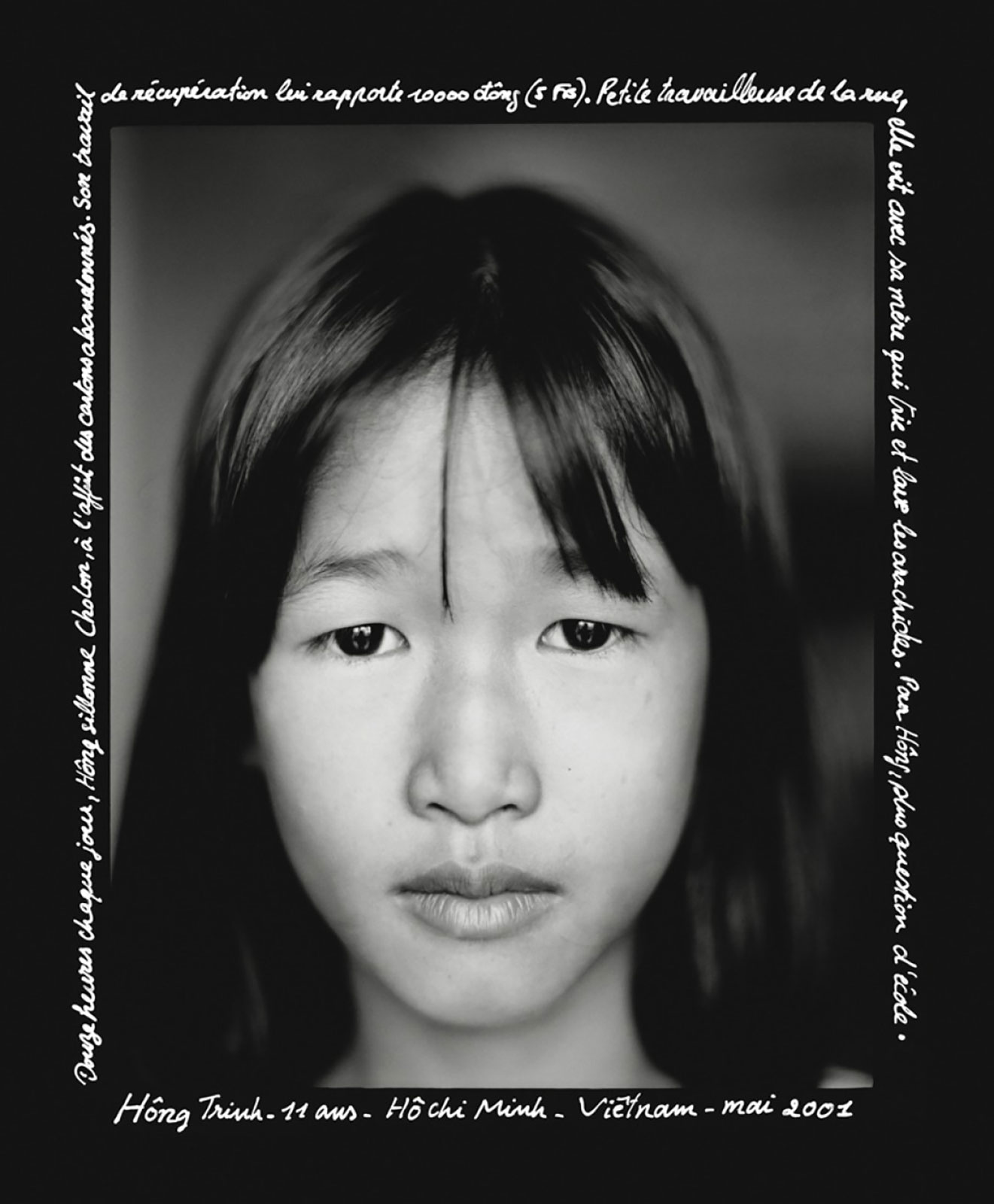

I’m fed up with showing children dying and suffering. I want to make portraits from up close, just showing the faces and not the background. In their eyes, you could see their fatigue, their suffering, their sadness. Christian Cajouelle suggest submitting the series to the World Press Photo. I told him these were not photojournalistic pictures and didn’t believe that I won the prize.

I don’t consider myself a photojournalist. There is a theory that as a journalist, you should have an objective point of view. My photographs are subjective, showcasing my own reality. I want to live true to myself. I’m not even a photographer, just a traveller and a respectful human being.

My practice lies somewhere in between art and photojournalism. Somebody commented that my photos of horrible places are too beautiful. They criticized a lot of photographers who work like this, like Sebastiao Salgado, saying they make money off others’ misery. But I like Salgado because he could communicate such humanitarian messages to a large number of people. I’m not against aesthetic photojournalism.

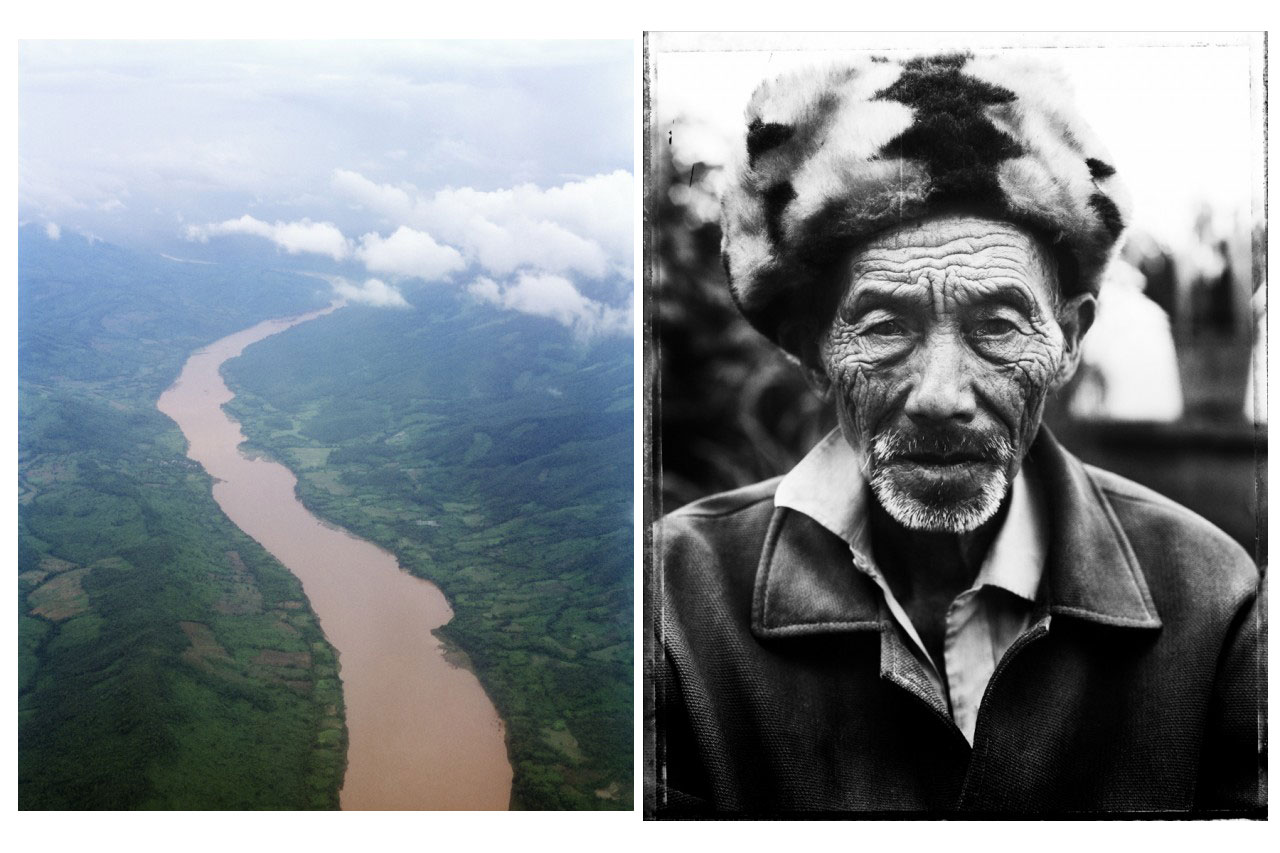

After escaping death in Iraq, I wanted to do something about the Mekong river, from the Delta to the source in Tibet. I was born on the bank of the Mekong river. I swam in the river and spent my happy childhood with my grandma. I had to live away from her for ten years and missed my family so much.

The river is both the border and the link. In Laotian and Thai, “Mekong” means the mother of rivers. It fits me because I grew up with my grandma and was surrounded by aunties.

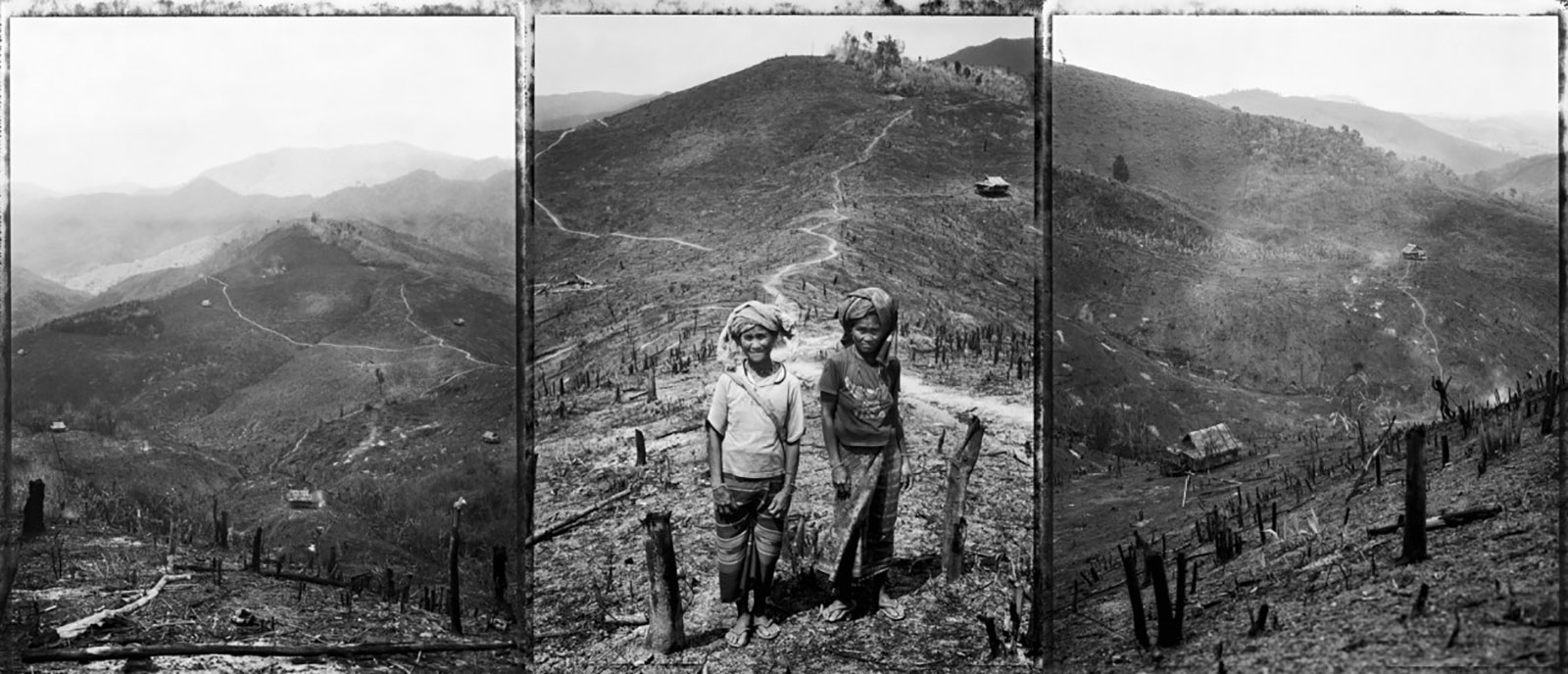

Instead of tracing its history, I wanted to portray the Mekong river through the eyes of people, how inhabitants are living, how they did economic activities like agriculture and fishing.

I brought several cameras with me, including a polaroid, a Leica, an X-pan and a Linohf, developing the negatives myself, traveling like the 19th century. It took half an hour to make a picture. Can you imagine doing that in the hot delta where people keep moving around? I kept the negatives in the water and gave people the polaroid prints. I did the same thing in Tibet which was 5000 meters above water. It was so cold that I had to heat up the films. One single picture costs a lot, so you have to be very precise.

Vietnam is my heart. I have Vietnamese citizenship. My grandmother used to live in Vietnam, and when I came here, I could eat dishes that reminded me of my childhood. My grandmother used to make black sticky rice with alcohol (nếp cẩm). As a child, I was not allowed to drink but I loved to eat the rice. I came to Hanoi and my friends took me to a restaurant where they served it and it made me think of her.

I once gave up photography due to personal issues. I left the agency and magazines, I just wanted to do something else, to be with myself. I did not want to push myself. I just wanted to be free. And freedom often requires a lot of sacrifices.

I have so many interests in life. Every morning, I enjoy doing yoga, meeting nice people, doing gardening, drinking tea. I’m not afraid of bearing the burden of war on my shoulder, because if I’m not strong enough, I won’t go to the field. I can still enjoy life after coming back. I trust myself.

*This interview has been edited and shortened for clarity.

Lam Duc Hien has developed an involved work across the world, as for personal projects than for the press and NGO’s commands. He testifies to consequences of 20th and 21th century’s major conflicts on civilians in Romania, Russia, Bosnia, Chechnya, Rwanda, South Sudan, and above all in Iraq, whose he covered the territory for 25 years. He is deeply invested for the protection of natural resources, and documents also the influence and the evolution of a contemporary world along the shores of Mekong and Niger.

The prestigious World Press Photo had rewarded the photographer’s portraits of “Iraqi People” with First Prize in Portraits category in 2011.