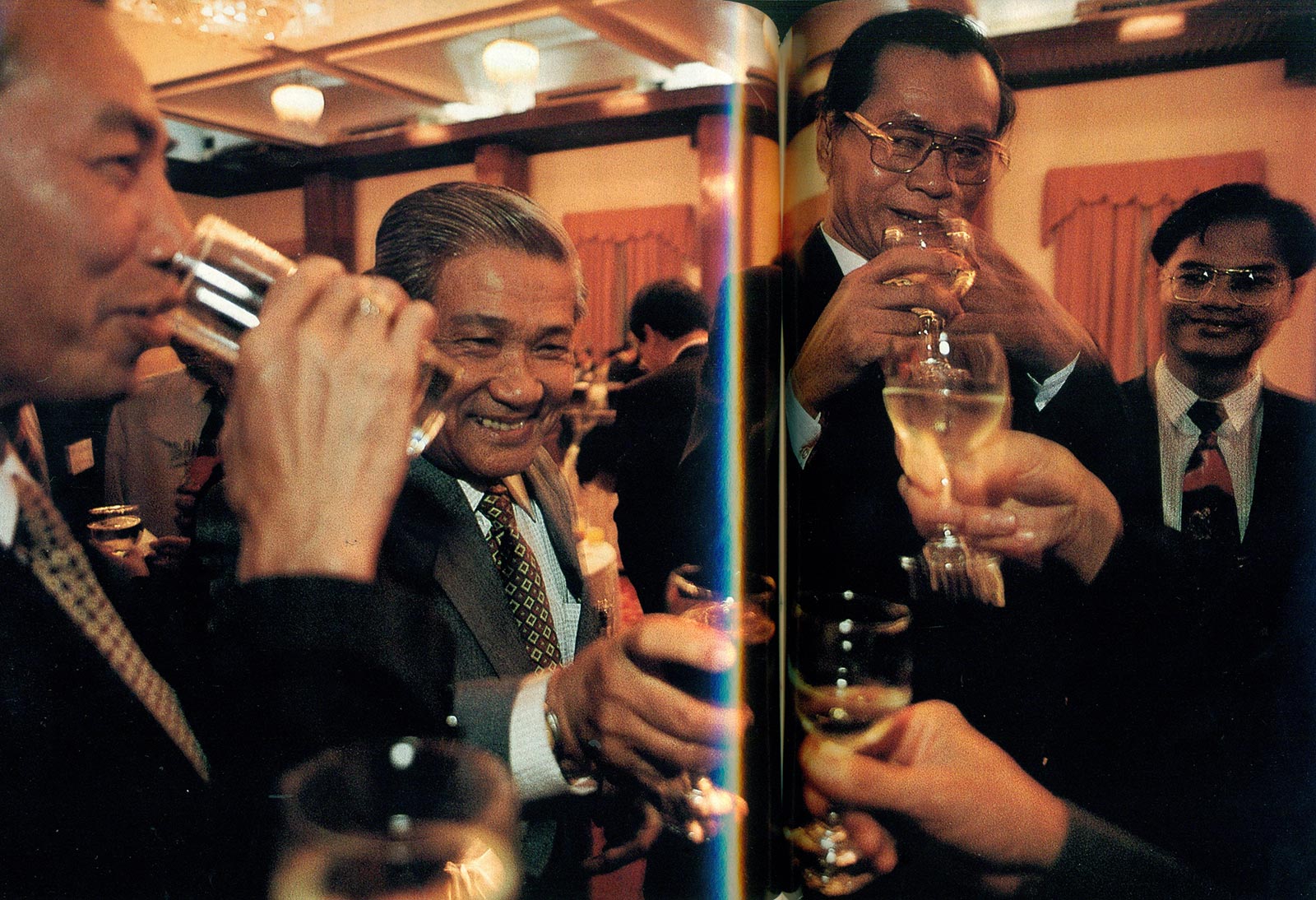

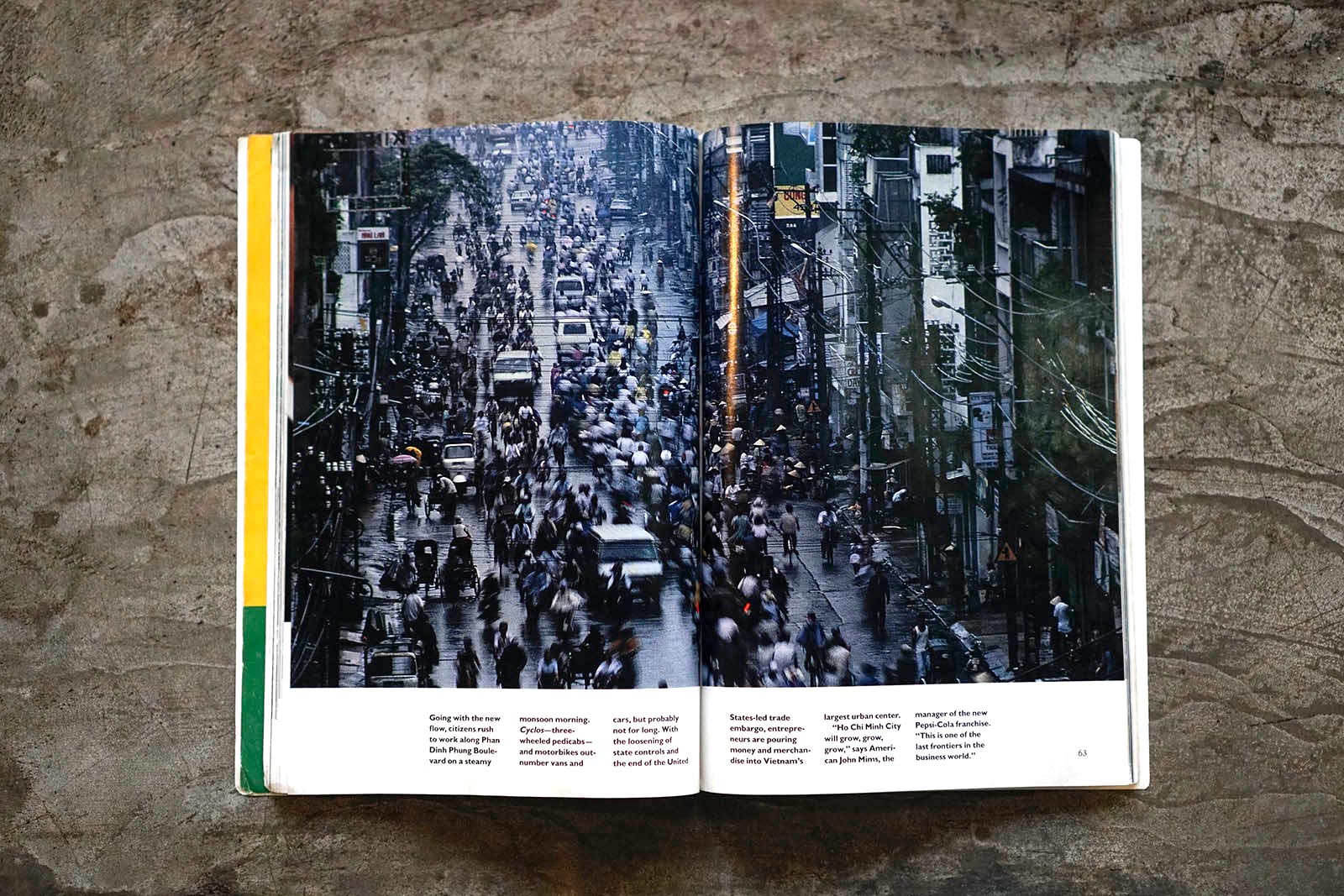

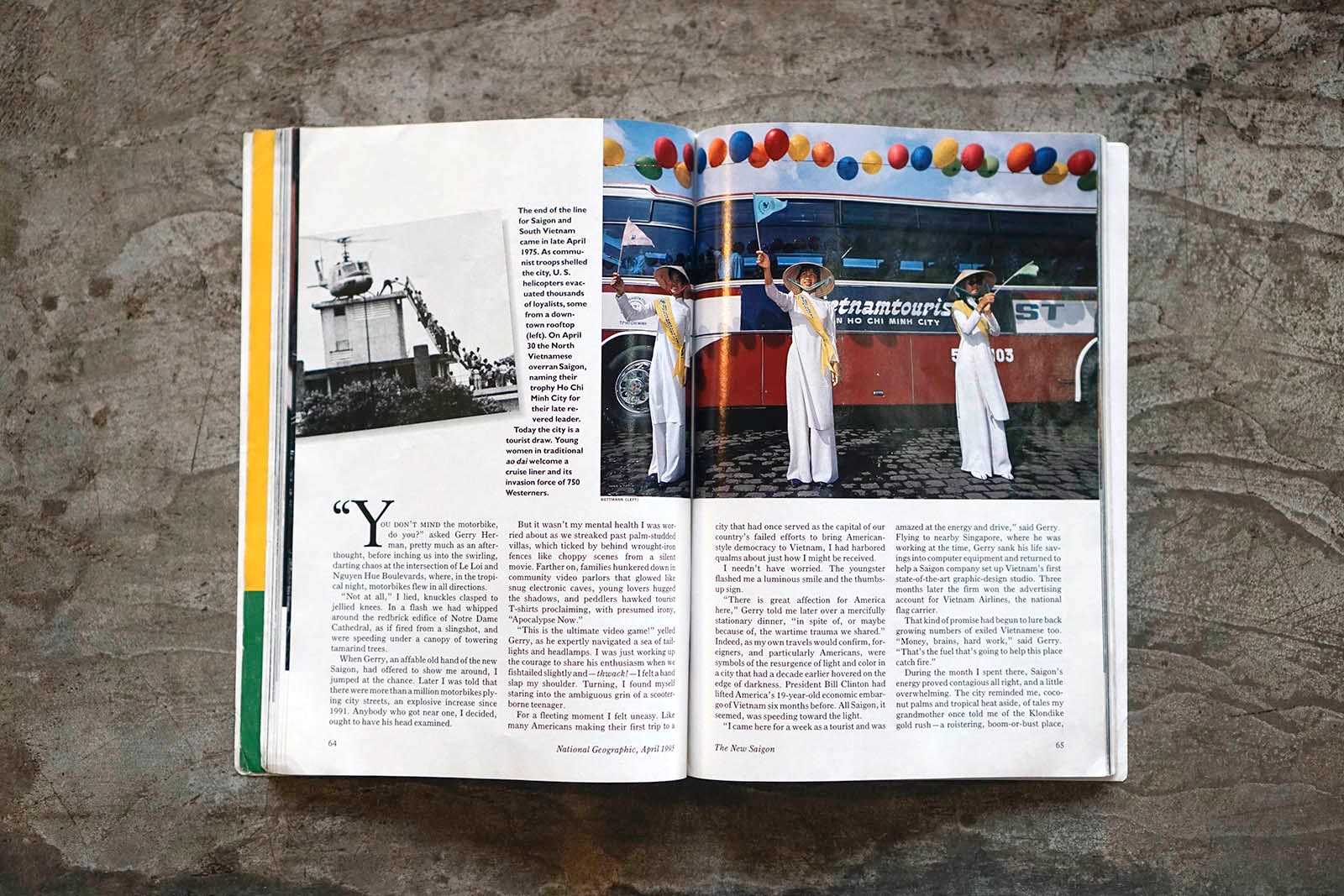

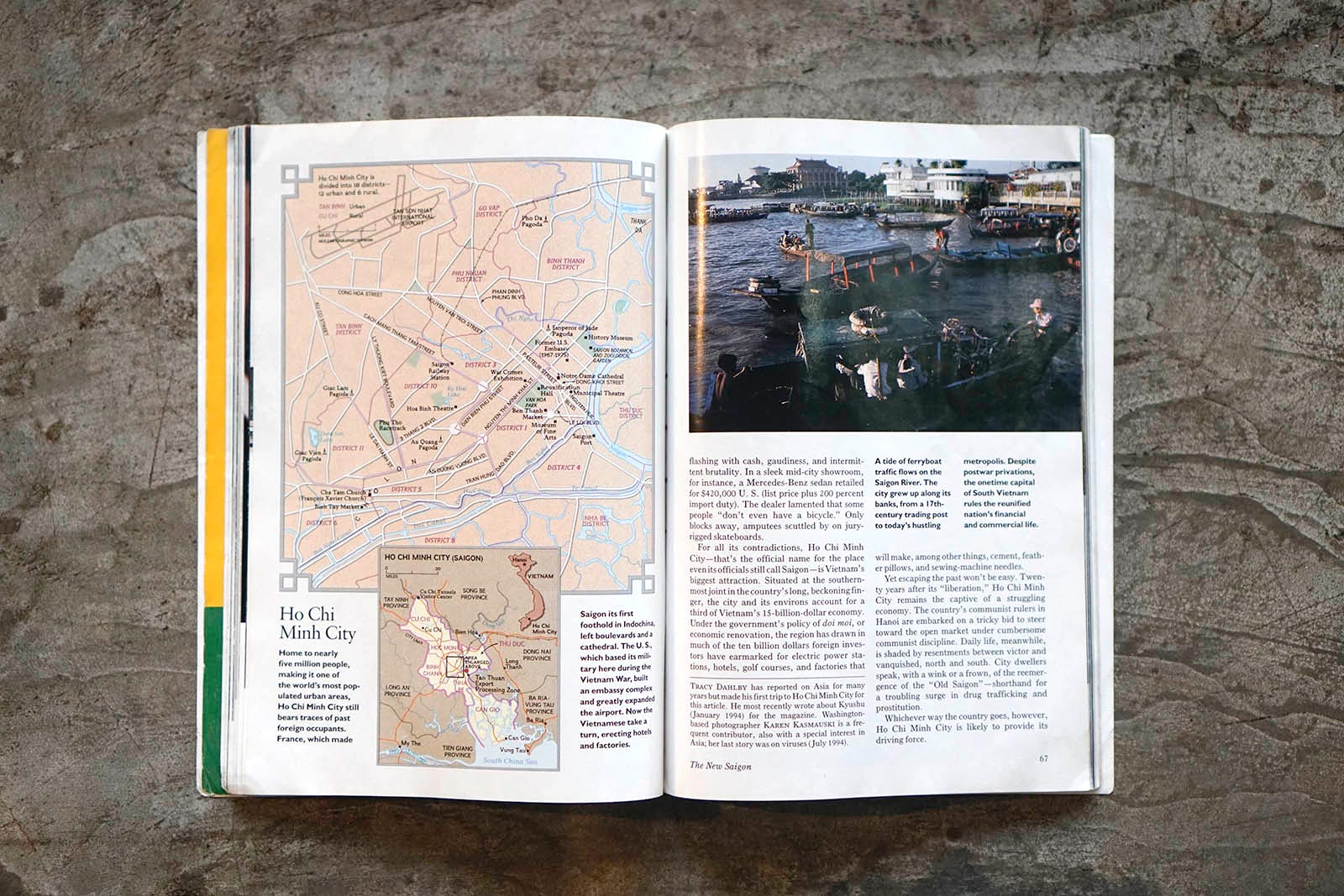

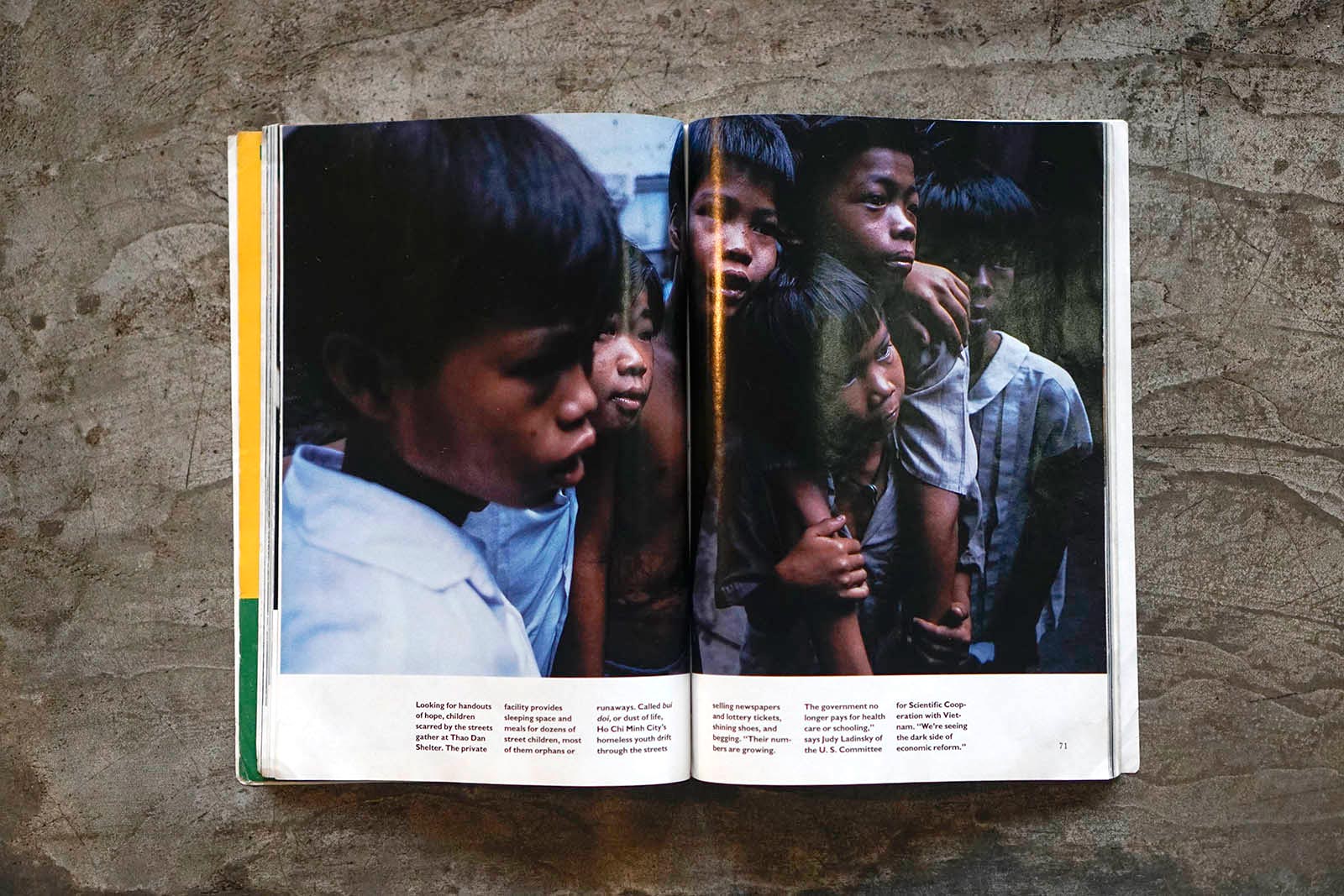

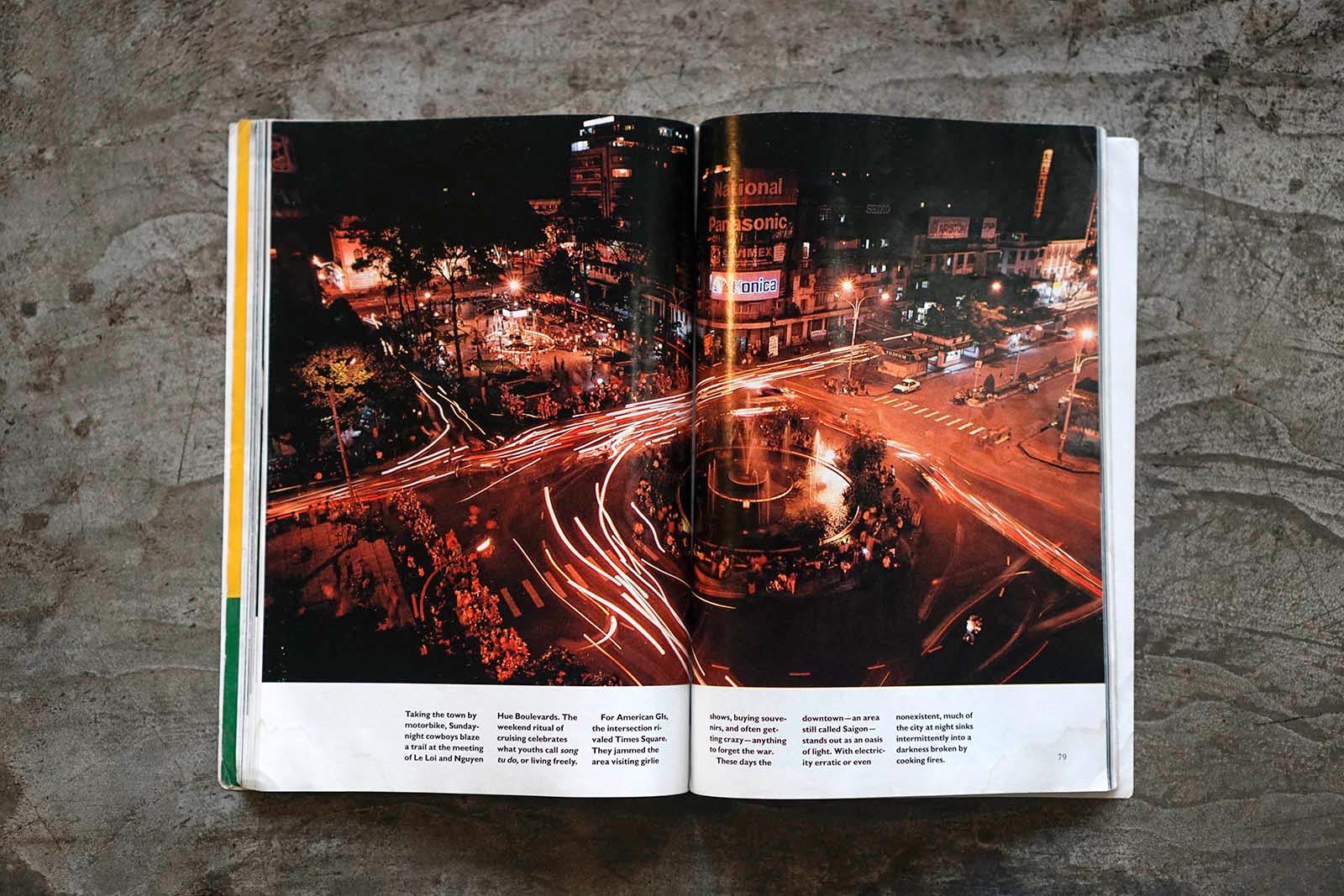

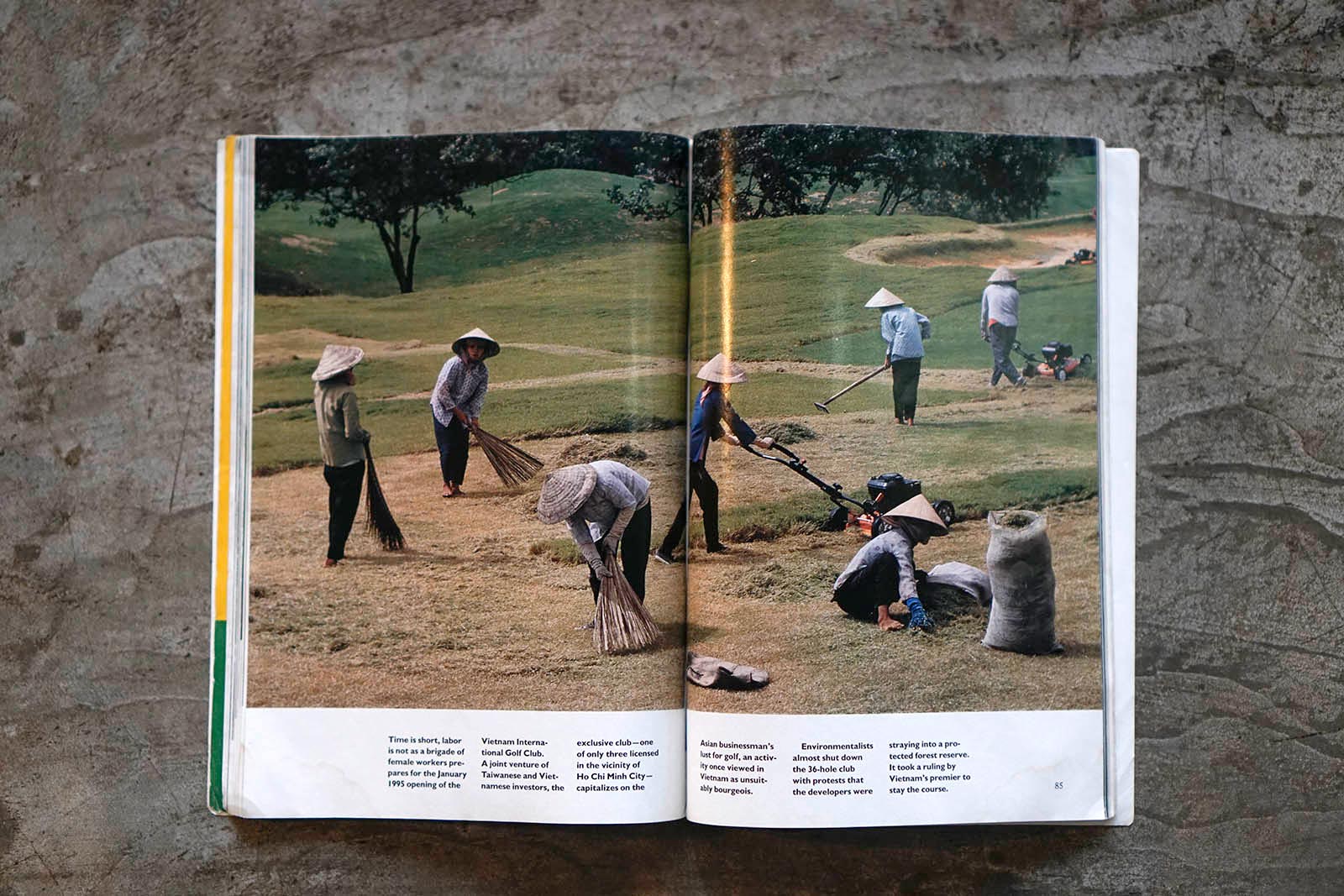

While strolling the streets of Kolkata, India, I by chance came across a newsstand that sold old National Geographic magazines. As I was rummaging through the dust-covered stack, a strangely familiar cover caught my eye. It was not of breathtaking landscape or an exotic animal, but a Vietnamese bride in white smiling with herself in the mirror. On the April 1995 issue, the title reads The New Saigon.

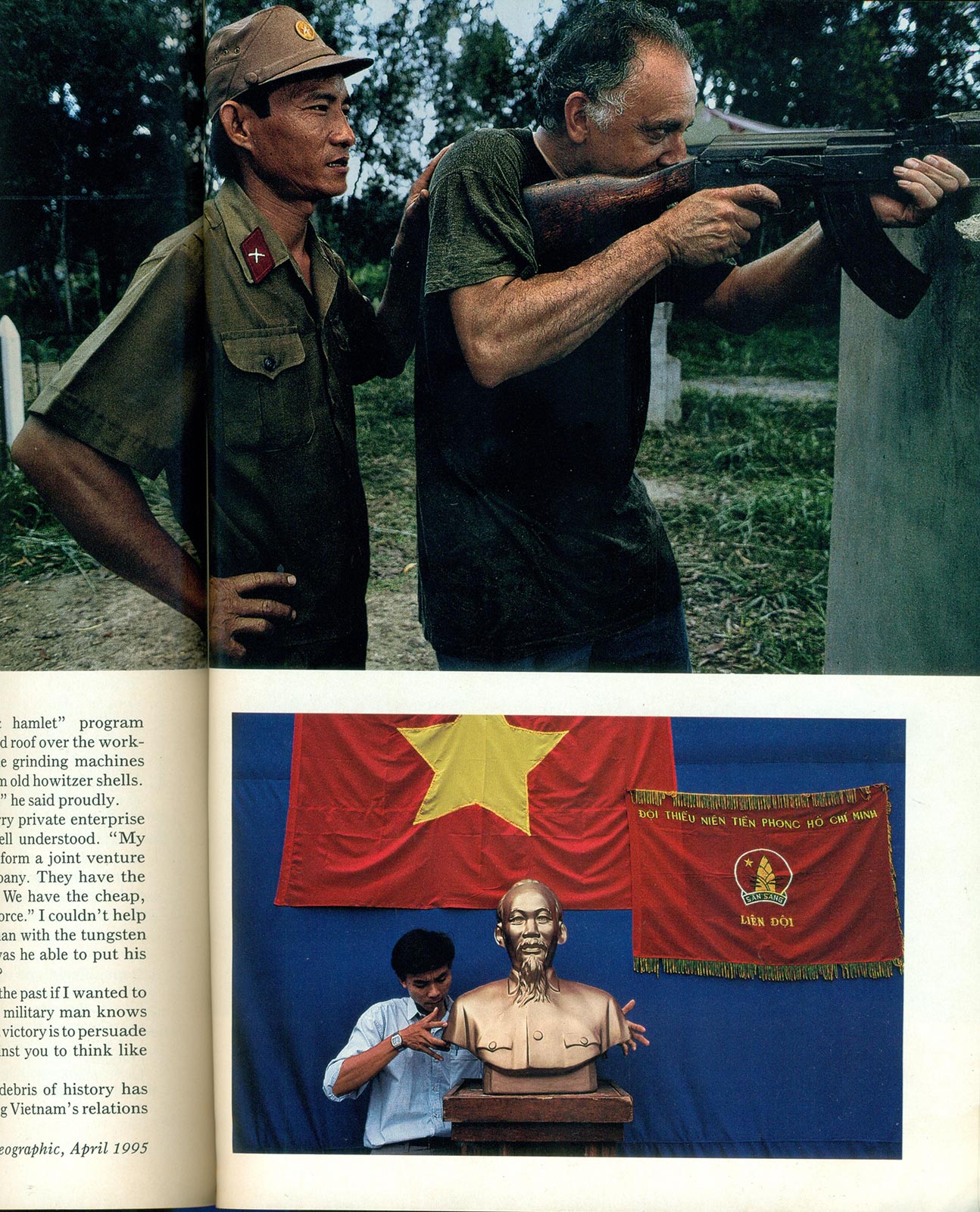

The 28-page essay was done by Japanese-American photographer Karen Kasmasuki. It was 20 years after the Vietnam War, just a few months after America lifted the trade embargo and nearly 10 years after Vietnam underwent Doi Moi with a goal of creating a socialist-oriented market economy. Via e-mail, she shared the story behind documenting the country at a time of transition and honest thoughts about a photojournalist’s job after a few decades in the field.

I pitched the story on Saigon because I wanted to see the city in which my father worked for nearly two years […] It was a huge part of our life and psyche. There was no Internet, no way to communicate with my father and yet here in the US we could see the war go on and on during the nightly news.

Can you tell us briefly how the assignment came to be?

The National Geographic wanted a story to commemorate the end of the Vietnam War back in the mid 90s, which would have made it 20 years after. I had worked on a Day in the Life project in Vietnam and had seen the country briefly. For this project, the photographers and project staff all met up in Saigon. I pitched the story on Saigon because I wanted to see the city in which my father worked for nearly two years. He had been there in 1954 as part of the US fleet that was helping people move from the North to the South, then returned again in the early 70s as the war was winding down. It was a huge part of our life and psyche. There was no Internet, no way to communicate with my father and yet here in the US we could see the war go on and on during the nightly news. Our family was having a non-stop nervous breakdown until my father returned safely.

Since Vietnam was just starting to open up to the world at that time, how did you do research and come up with a coverage plan for the assignment? What aspects of the city did you want to portray?

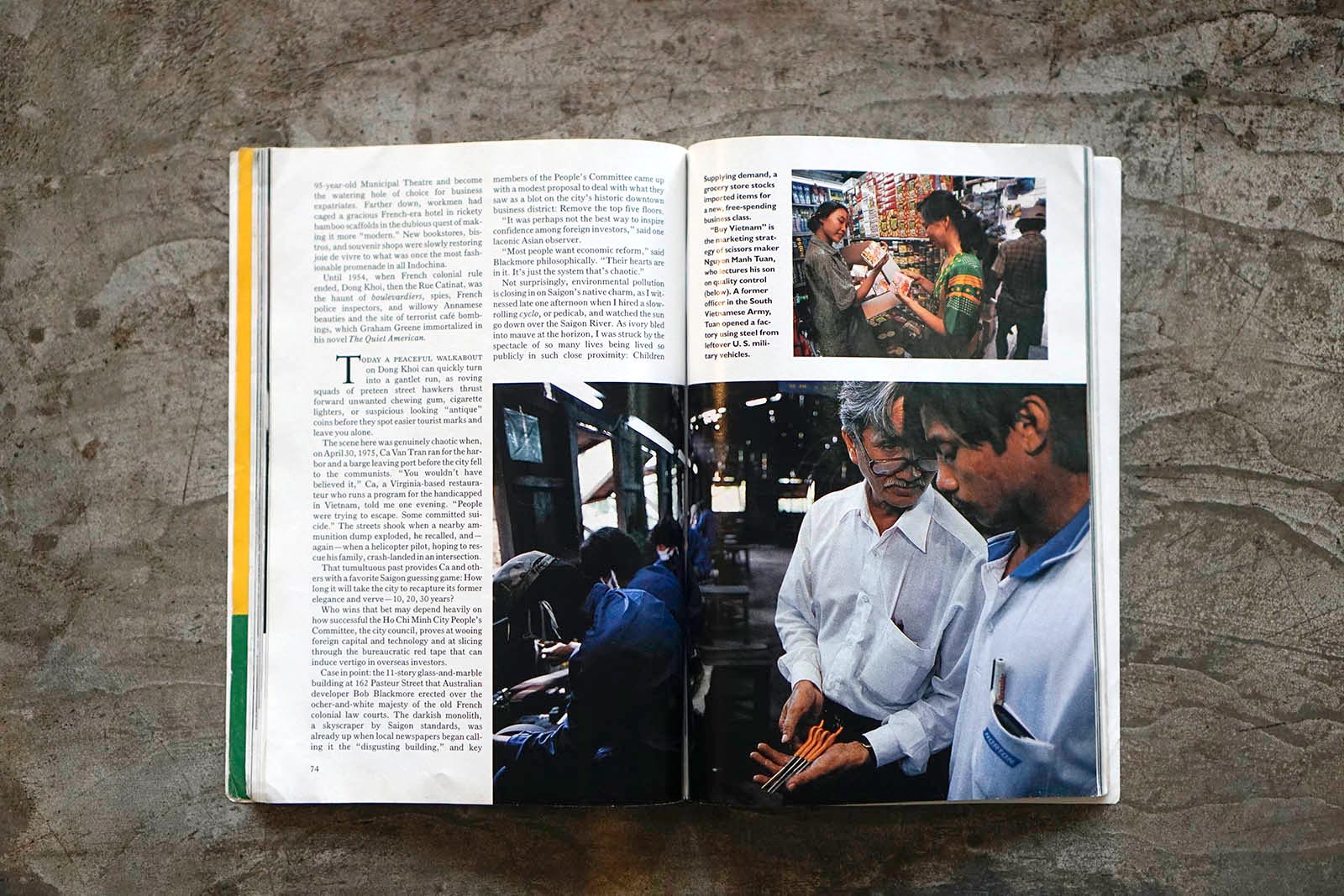

Working on that Day in the Life project gave me a little insight but I wanted to have more time. I did the usual research journalist do before they travel to a location including finding books articles, papers done on the subject, plus I spoke to as many people I could who might have been there since the war. Today one can even look at videos or films to get information and the feel of a place. Most research is done online, but the best is to talk directly to someone who knows the subject. The key is to find your own interpretation and vision even after reading other people’s work or looking at other images.

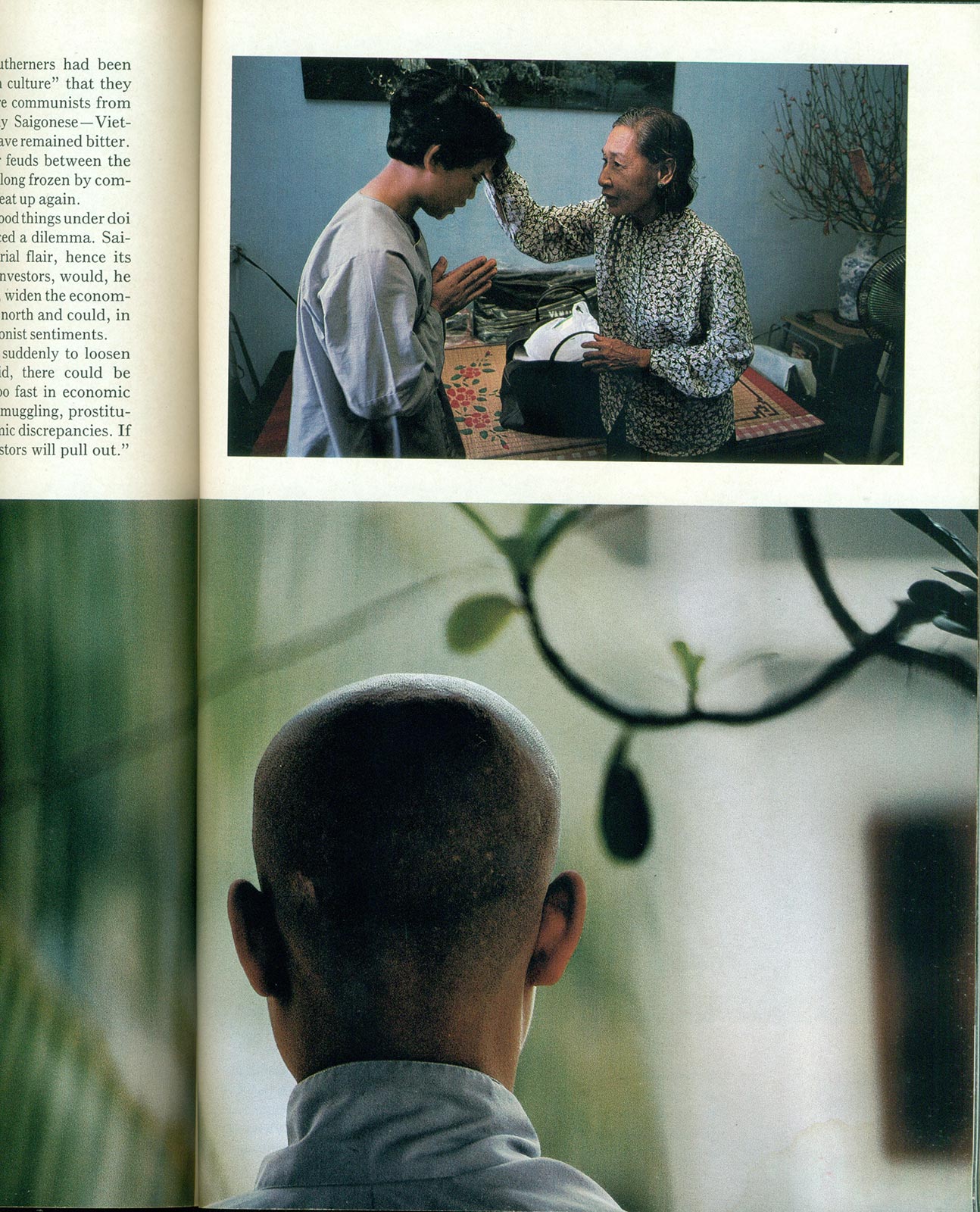

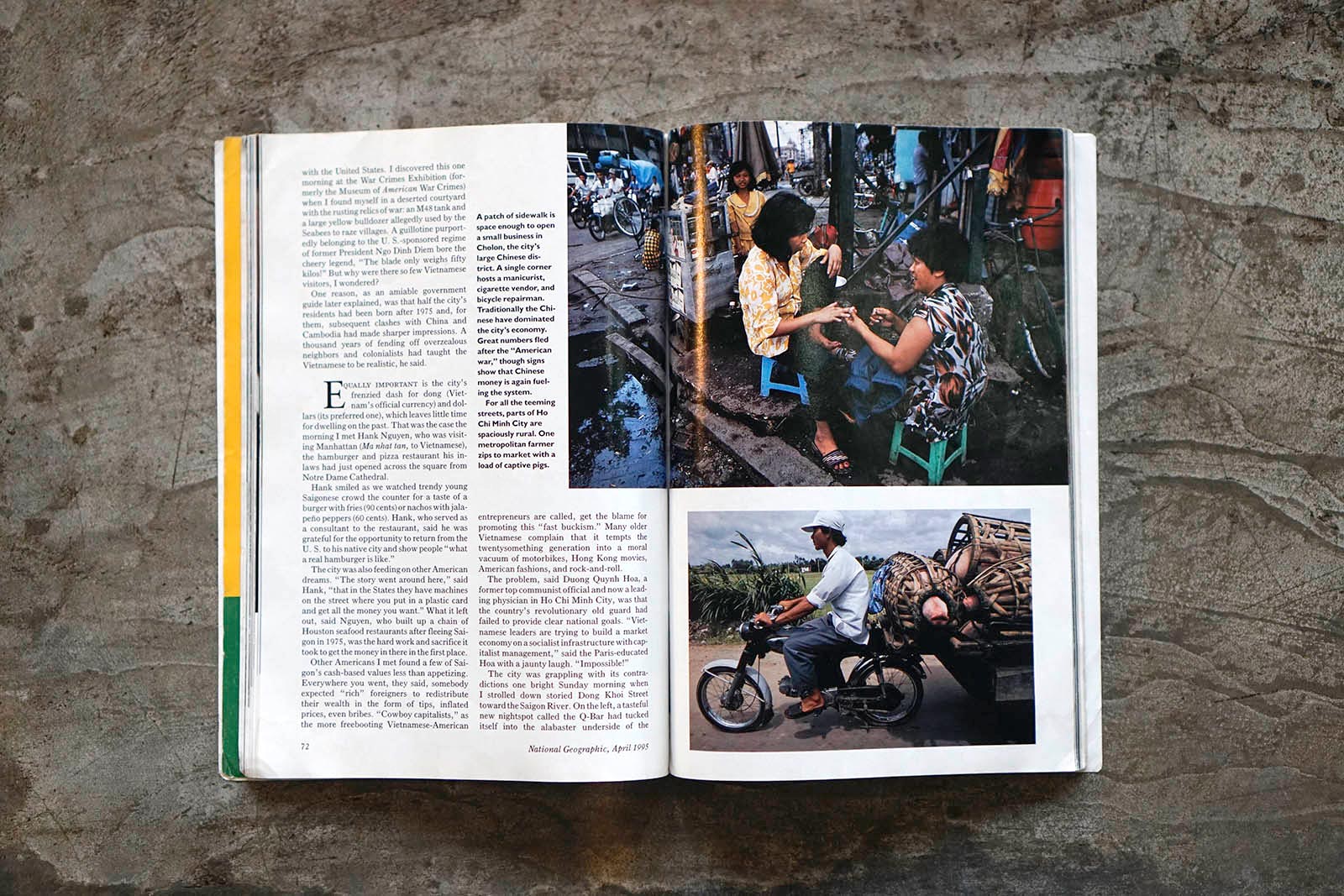

I had no preconceived idea as what Saigon was about. Once I got there, I was fascinated by everything I saw. I enjoyed being there at that time as it was still raw and not looking like every other major city in Asia.

For the final result which is a 28-page story, I wonder how long it took and how many rolls of film you used. Also, how you collaborated with the writer during the assignment, since your photos could stand alone and did not serve the purpose of illustration.

It took several months to do the story. I really don’t remember how many images I took. Also it really doesn’t matter, what matters is whether or not the ability to reuse cards and throw images away now so quickly have made us sloppy shooters. I think it has. I even find myself taking more images than necessary and sometimes shooting without really thinking about composing the image because I know there is no additional cost and I can always throw them away. When I was shooting film, I was well aware of the cost of each roll. Even when I worked for National Geographic, the cost of the film used on assignment was charged against the assignment budget.

I never traveled with the writer. Similar to other stories I worked on during that time, my editor and myself would have several meetings with the writer and his editor to make sure we were all on the same track. Then we’d have a meeting with the editor of the magazine to be sure he was on-board with our approach.

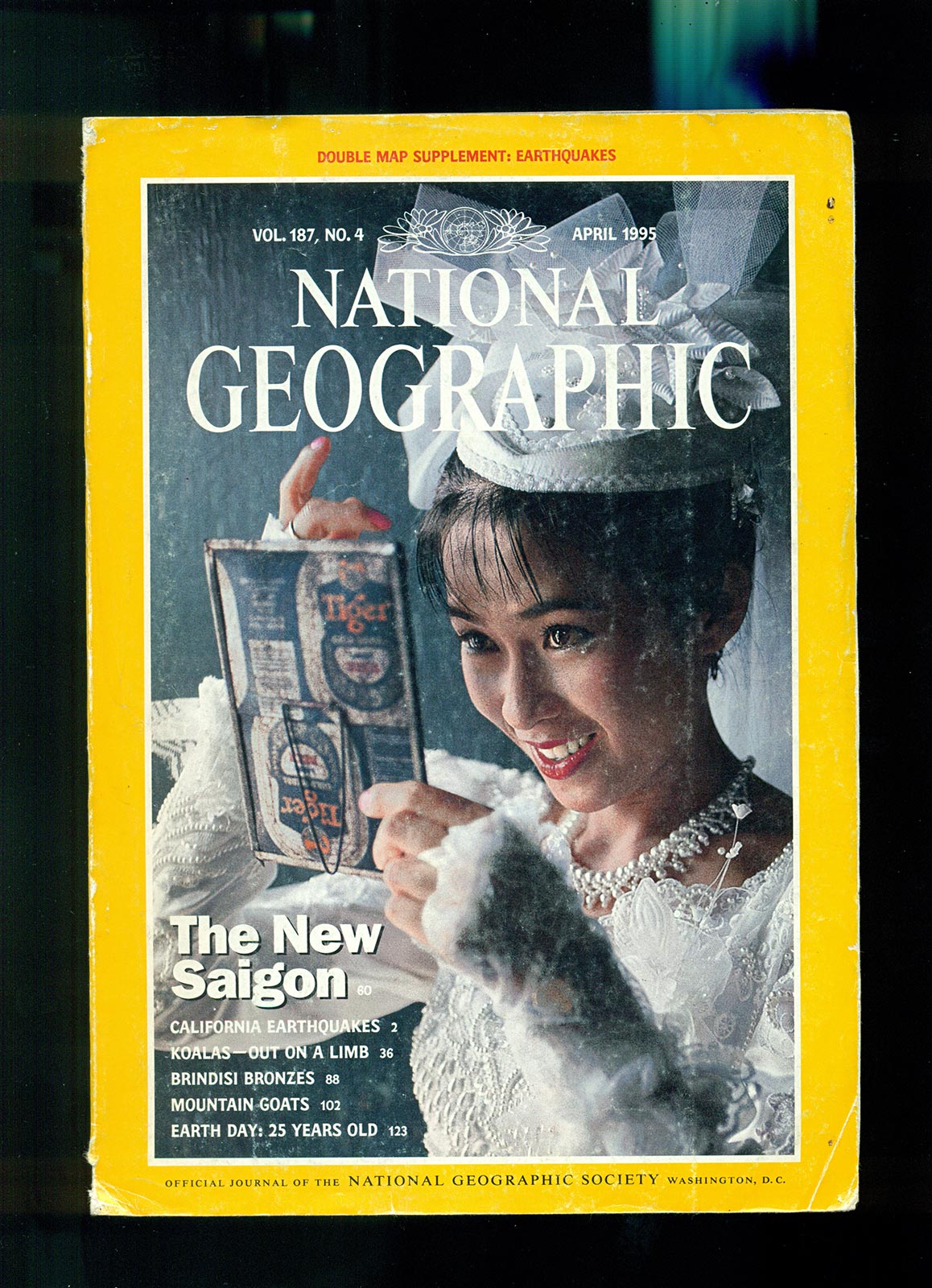

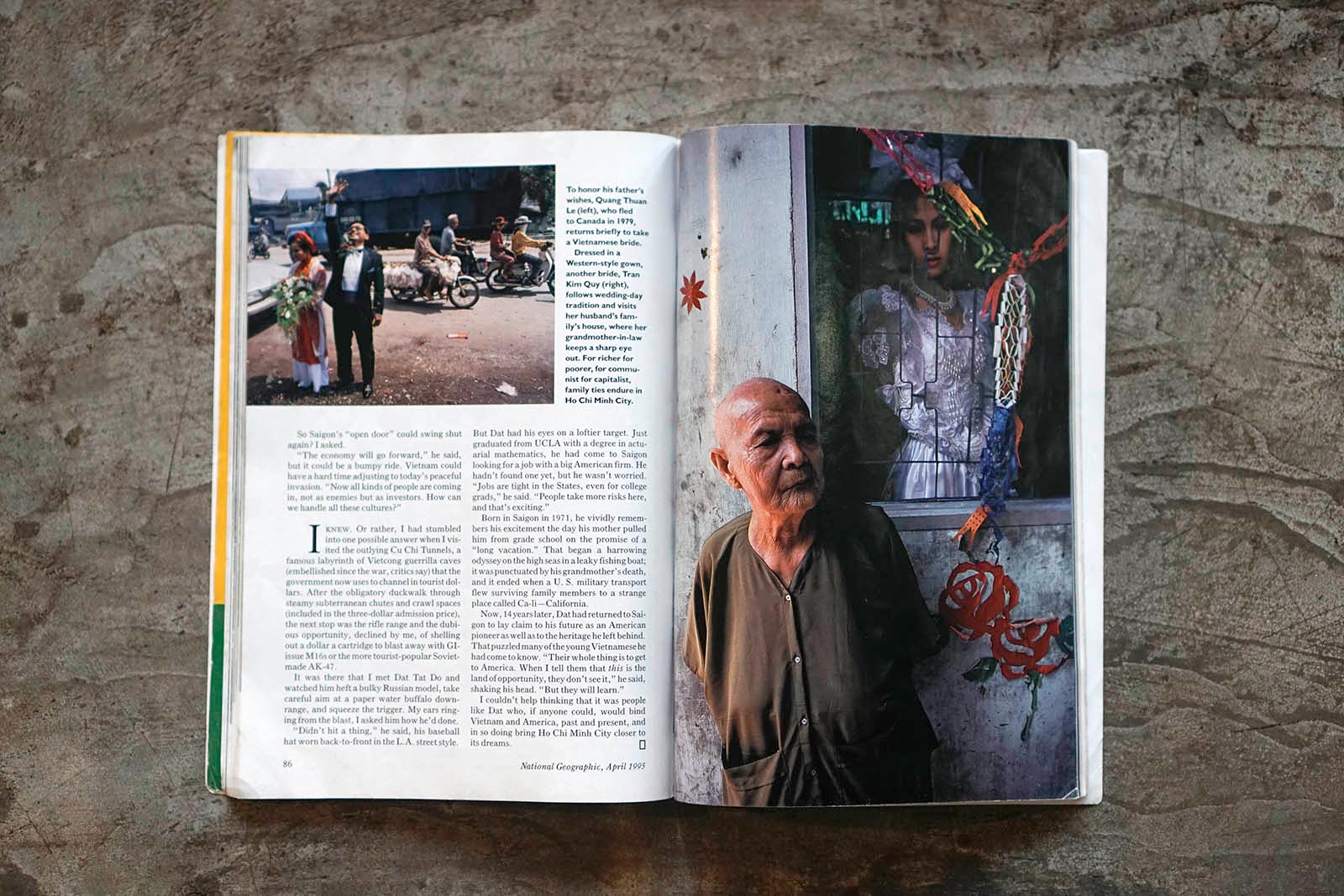

The cover of the magazine depicted a young woman adorned in white bridal gown smiling at herself, the mirror she held was embedded with a flattened Tiger beer can on the back. For me it was a powerful image as it was able to convey a time when Vietnamese people were just lifted out of poverty and consumerism was looming over the horizon. Can you share the story behind the cover image? Why was it chosen by the editor to be the cover?

I worked with an amazing guide on this story; I was lucky I was a woman so the government assigned a female government guide to me. She was the most talented and amazing guide and I loved working with her. She knew what I needed and would often track things down on her own. My guide was always on time, never missed a day and kept in continual communication with me. When we went to the main market in Saigon, we met this young woman and found out she was getting married to a fellow seller. We asked if we could photograph their wedding and the preparation for it. They agreed. We thought that even with so little these people wanted to celebrate such an important event as a wedding in a traditional way, with Western overtone (the white wedding dress) to show that they were somewhat successful as market sellers. I had a great time photographing these two young people and their extended families.

I think the cover was chosen because of how impactful the Vietnam War had been to those of us Baby Boomers and our parents. This story commemorated the 20th anniversary of our involvement; the editor thought it important enough of a story to make it the cover. By coincidence, it was the first magazine to launch our Japanese Edition of the Magazine. Their editors opted not to use the Bride on the Japanese National Geographic Cover as they wanted something more “traditionally” National Geographic, I think they chose an animal.

The National Geographic magazine was a door to the world to many people. However, the way images are produced and consumed are vastly different now compared to the pre-Internet era. In a world now inundated with photographs, has the role of a visual journalist changed?

The basic role of the visual journalist to tell a story visually has not changed. What has changed is how it’s delivered to an audience and sadly because of the proliferation of photographers, it’s also harder to make a living than it was when I first started over thirty years ago. I think this is a good topic for discussion, especially for younger photojournalists. It is harder now to get people to linger on images taken and be moved by them. Images pass us by at a rapid rate and I often I wonder if people are affected other than an initial peak of interest.

After working as a photojournalist for a few decades and experiencing these changes in the industry, what keeps you moving? Do you think photojournalism still holds sway and how can visual storytellers find a way to better engage with the easily distracted audience?

I have no idea what the answer to your last question is. I was just talking to a friend about that. Not only is the audience distracted but there are so many images out there, many of them though beautiful are meaningless. Also with all the processing software, images don’t even look real anymore. Sometimes they look more like drawings than photographs…The lines blurred. I feel this is why people looked images as passing illustrations. Images have become our new white noise. Most people don’t pay attention to them except in a fleeting manner.

I feel like what we photographers do is mainly talk to ourselves. We pat ourselves on our backs about how edgy and how truthful our images are. Does the public really notice or even care?

I have to make a living so I need to do this as long as I can. I don’t have a trust fund or a rich mentor. Working is survival and maybe that is a good motivation. However the projects I like to do, long form storytelling are getting harder and harder to find funding.

During her two decades as a National Geographic photographer, Karen Kasmauski produced 25 major stories for the magazine on topics including Human Migration, Viruses, Aging and Genetics. Karen’s previous book “IMPACT: From the Front Lines of Global Health” examines the causes of infectious diseases throughout the world and the documentary film “Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight—The Japanese War Brides” she directed aired globally on BBC. As an educator, Karen leads photography tours for National Geographic and other clients in locations ranging from Antarctica to New Guinea to the Galapagos. She also gives classes on video storytelling, photojournalism and news writing.

View more of Karen’s works on her website.