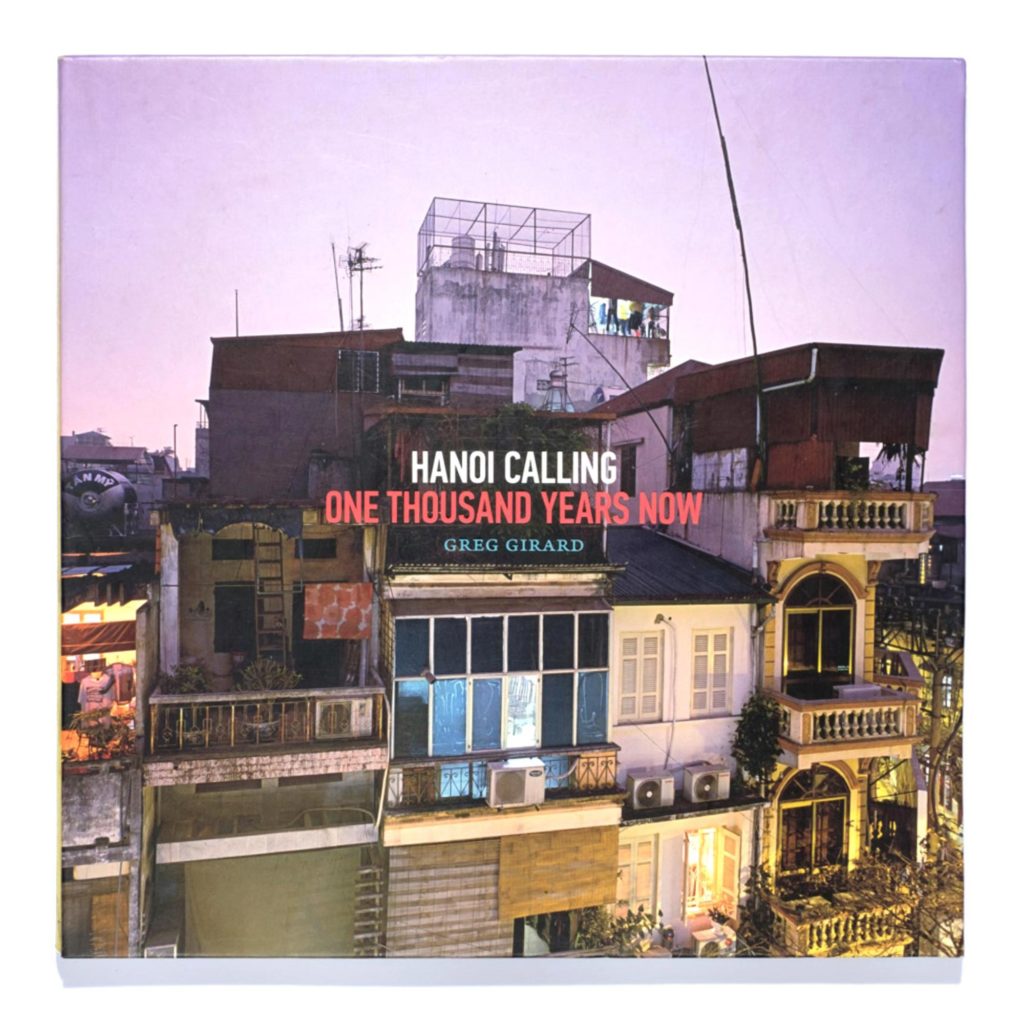

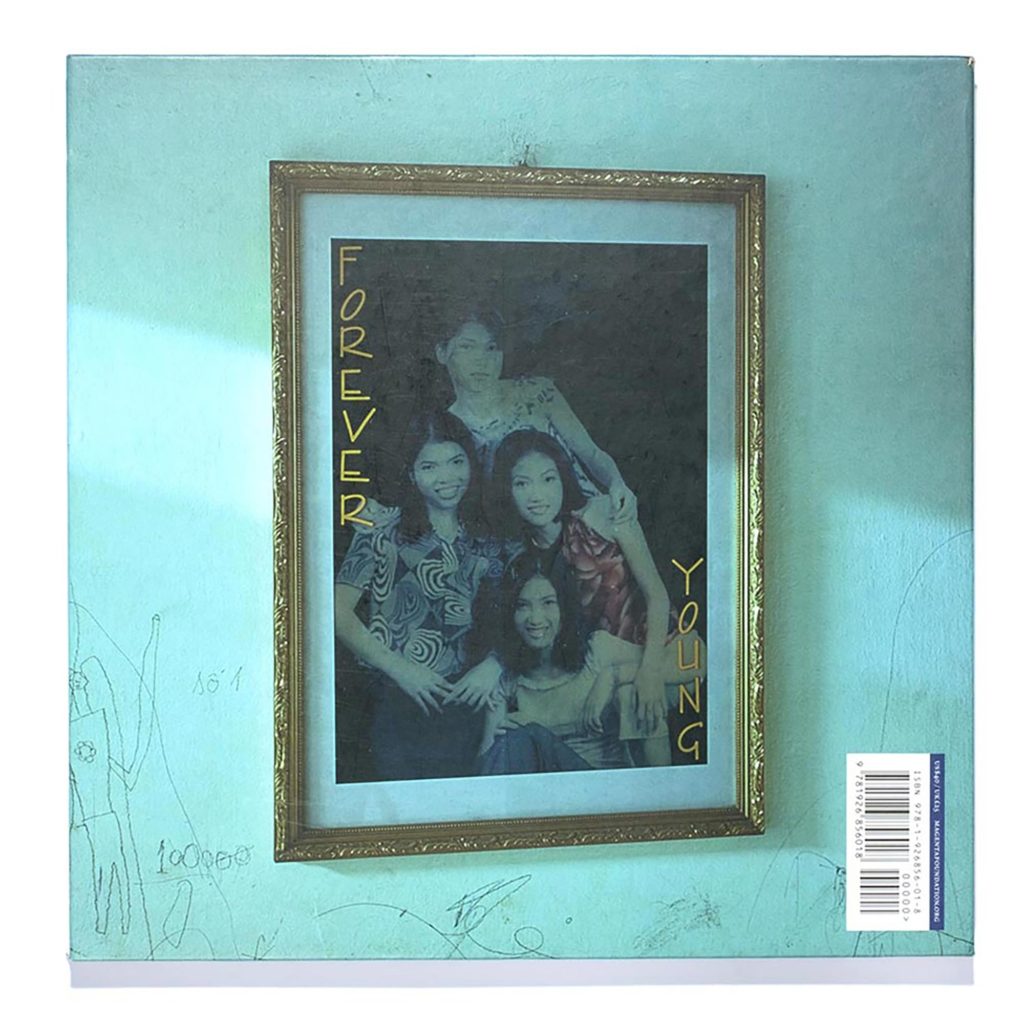

Greg Girard answered the interview from his hometown Vancouver, Canada, where he returned after three decades in Asia. During this time, Girard has documented many cities in transition, including Hanoi. We revisited his Hanoi Calling book published ten years ago on the eve of its millennium anniversary. While the front cover presents a panorama of the cityscape at dusk, the back reveals a more intimate view. A group portrait of four young women hung on a turquoise wall, partially lit by a gentle sunbeam. The children’s drawings on the wall implied the shared nature of domestic life.

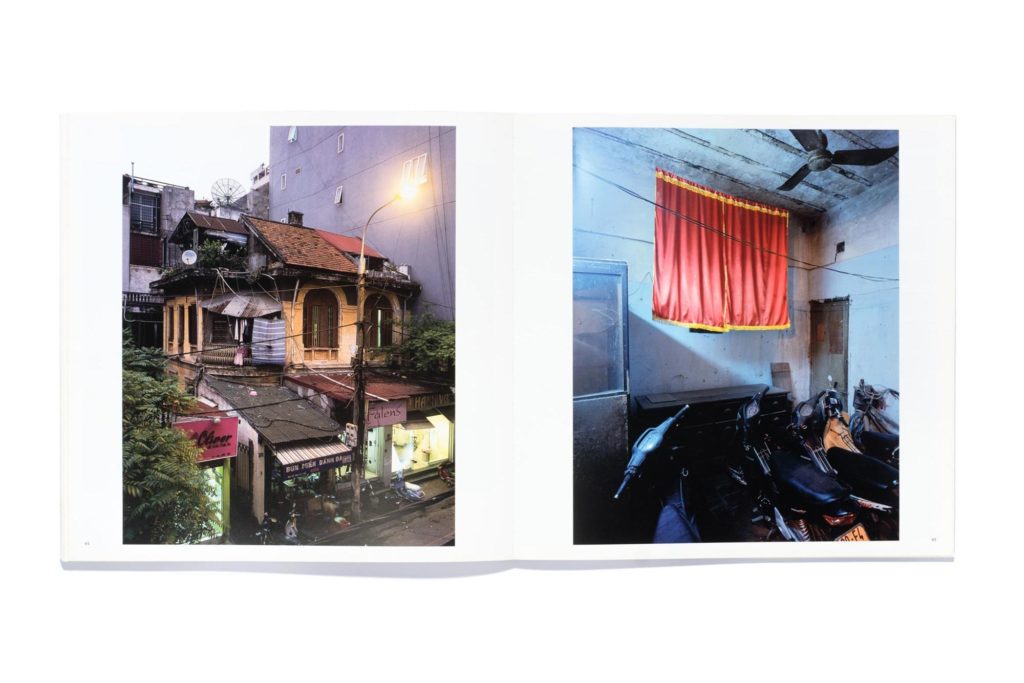

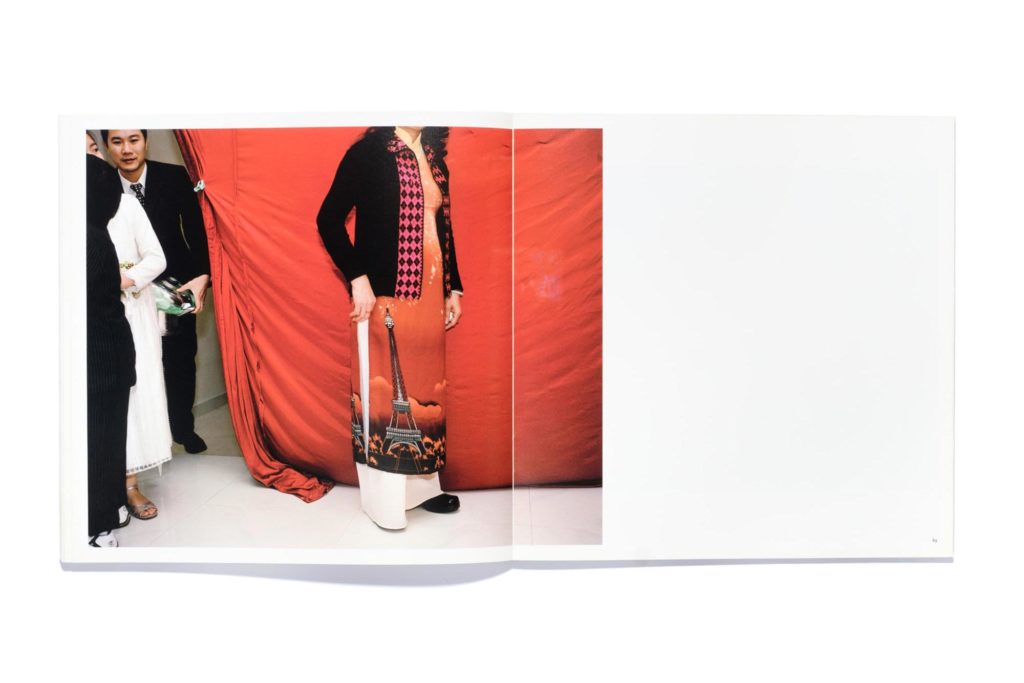

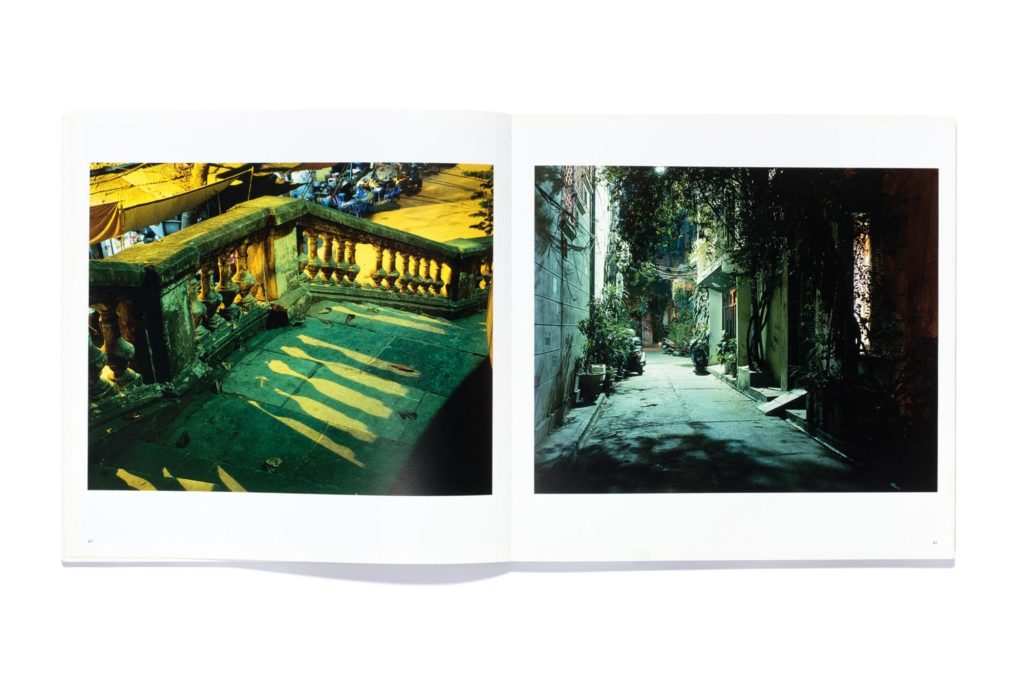

The detail speaks of Girard’s practice: to observe intersecting elements of daily life on the street and inside homes where families spend time together. Combining portraits, landscapes, and still lifes, Hanoi Calling explores how city dwellers interact with their built environment – the unique architectural heritage in tandem with planned and haphazard urbanization. It remains a common theme in his body of work spanning across different countries and time periods.

Yet perhaps more than the peculiarities of each place, what Girard was keen to capture is a sense of light. Whether shooting a hazy winter morning in Hanoi’s West Lake, neon signs on the backstreets of Tokyo, half-destroyed houses amidst the surrounding high-rises in Shanghai, or snapshots of actors on TV screens in nondescript hotels, he looked at how the qualities of light hide, reveal and transform faces and sceneries.

“This isn’t the stuff of high drama. It’s really just about putting in the time, and being persistent and sometimes lucky”, shared Girard. Not to draw a simplified contrast between what has gone and what is to come, his work reminds us of the fundamental function of photography: to see and to care.

Let’s start by going back to the very beginning. You first moved to Hong Kong in 1974 to work as a sound recordist for the BBC. How did you go off-track and turn to photography as your medium of choice?

I had been photographing long before I became a sound recordist. As a teenager attending high school, I started documenting downtown Vancouver. I grew up in the suburbs so it was a very different world to the one that I knew. That was the first big lesson about how a camera could take you into another world if you let it.

I had no experience and just learned on the job; I’m not sure if that’s possible anymore these days. Although sound recording was my job, by immersing myself in the world of television news, what I learned was how to arrive in a place I’d never been and within a few hours gather enough materials to make a news story. The experience of working under deadlines allowed me to leave the BBC and later start working as a magazine photographer. That was a big step.

You once referred to taking photographs of Hong Kong as a way to “make Hong Kong mine”. I wonder if you can elaborate on that idea.

Making a place my own means to find my place in it through photographs, whether I belong there or not.

The reason behind most of my projects comes down to the fact that I’m not seeing the pictures that I want to see. There simply weren’t images that represented the Hong Kong that I knew in the 1980s except for certain films, mostly gangster or crime movies dealing with the less beautiful side of the city. There were some filmmakers who by accident or default ended up making documents of the period, but I didn’t know of any photographers who shared the same interest. I just started making pictures at night and pictures of ordinary Hong Kong and had no idea if they would be seen by anybody.

Without having thought about it in any theoretical or academic way, I have always felt that the measure of my pictures was whether they were liked or appreciated by local people. They walk by it every day, but the way a city looks in photographs is its own reality.

After working for magazines for two decades, you eventually left editorial photography to focus on your personal work. What drove that decision?

In the beginning, it overlapped quite perfectly with what I wanted: to be a photographer and make a living. But eventually, I decided to draw quite a clear distinction between the pictures I would make for myself and the ones I was assigned to do. It’s not that I didn’t like the assignments; they were a fascinating way to get to know a foreign country and see some of the most extreme things as well as daily life. But on a personal level, I knew many pictures I spent most of my time on would have no place in magazines. There were a lot of hidden subtexts, such as the editors’ filters, the type of publication, their mission and relationship with advertisers.

In my case as a Western photographer working for Western publications, there are two things to consider: one is the presumption that photographs are directed at the audience in the West, and the other is the stylistic look that characterizes the photographs as pieces of visual information. These parameters are extremely vast and have evolved over time, but certain presumptions can, if you let them, dominate your picture making.

The Phantom Shanghai photobook happened when I made the decision to leave the magazine world, which I felt had run its course. It also coincided with the time when the world was in a honeymoon phase with China. Many people were visiting the country for the first time, so there was a certain amount of personal romantic connection. The work resulted in an invitation to be represented in a Canadian gallery, and subsequently, I have been making books, so those are other ways to sustain my practice. I worked hard but that was the minimum part. There were many things that had to fall into place, and lucky for me, they did.

That leads me to your Hanoi Calling book, which was a result of a commission. I wonder if you could share what interested you about the place.

I was very excited to receive the invitation to make a book about the city. I never lived there, but had known Hanoi a little from previous assignments in the 1990s. It felt like a living museum to me. A kind of unintentional preservation was going on because urban development for profit hadn’t happened yet on a large scale. I felt acutely that this was a special time and a special place. There is some similarity with my work in Shanghai, where it’s an overlooked space with a kind of low-tech and high-tech hybrid.

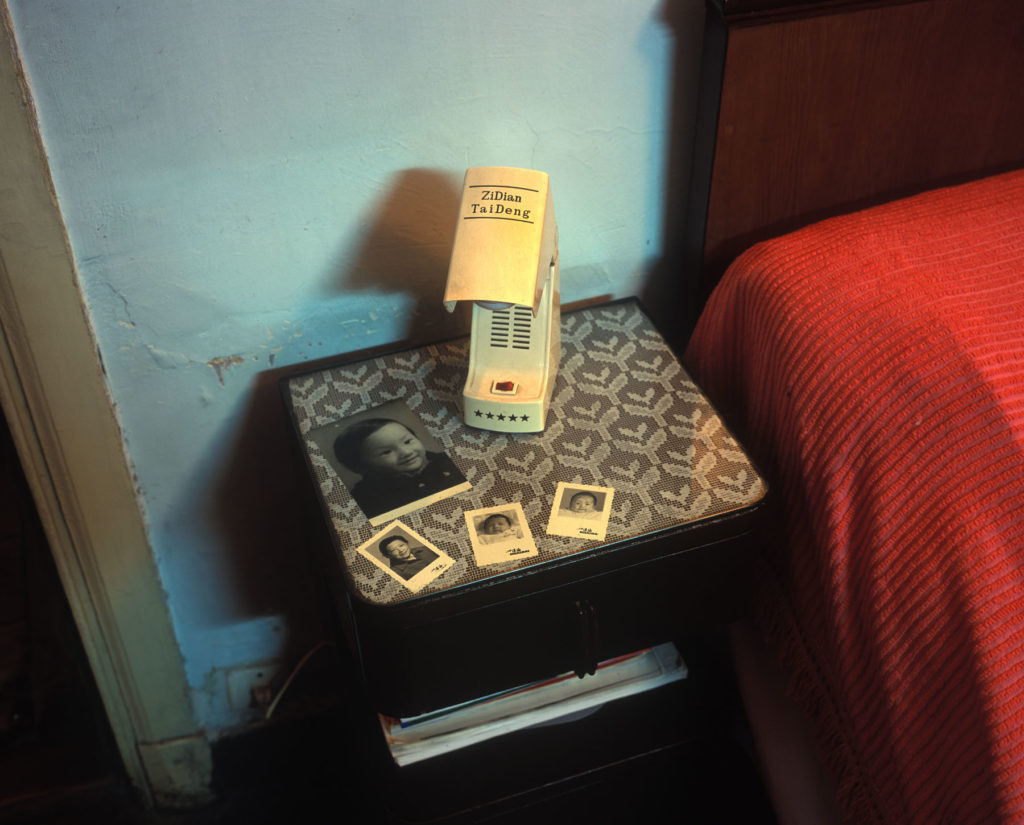

Instead of dramatic moments, the book gives space for tender frames of living spaces and still life. May I say you were looking for the extraordinary in the mundane?

The interior scenes are intimate, private, hidden from the public. They are things you are not supposed to see. That’s a treasure that I got to see and experience, and I hope that feeling comes through in the book.

Most photos were taken on a tripod, so that’s a good way to slow down right there. It eventually takes more time and equipment to make each picture compared to digital photography, so you want to make it count. I enjoy walking and looking, either at dawn or early evening and into the night. I spend time during the day as well, but I do lean into the transitional hours when a city reveals itself in a certain way.

I never thought of my practice in any verbal way, but seeing something extraordinary in the mundane is probably a good way to put it. There is a kind of buzz in seeing in a scene that this could be interesting, which can happen with or without having a camera. It’s an ongoing thing for me anyway.

There is a kind of buzz in seeing in a scene that this could be interesting, which can happen with or without having a camera. It’s an ongoing thing for me anyway.

You are known for documenting the transformation of big cities, and some places in your photographs no longer exist today. What was on your mind when taking them?

I have never made a picture thinking “this would be interesting in 20 years”. I don’t know for a fact these places are going to disappear, but I sense that they’re slightly overlooked and not fully appreciated. I realized now that these pictures after some years may be appreciated in a way they weren’t at the time they were made – not just with my pictures but with photography in general.

In a place where the everyday looks a certain way, it might take an outsider to see it differently. I don’t know why Hong Kong photographers didn’t care about the things I did in the 1980s. A lot of young people are now photographing things that might be on the verge of disappearance or have this historic vibe, but before that, a certain point has to be crossed. Maybe the same thing has happened in your city. As recently as 10 years ago, people didn’t appreciate things like they do now.

How do you see publishing platforms like photobooks and later Instagram as an outlet for your work? Your old photos seem to be garnering a lot of attention on social media.

Books are how photography came to me and how I came to photography. Library books and photography magazines were the masterpieces where I saw somebody’s vision, their view of the world, and at times of themselves. They were the touchstone that allowed me to see what photography was and could be. That early connection with photography through books has never gone away.

Regarding Instagram, I guess like everyone else, I just tried it out without thinking too much. After I posted my actual work instead of daily phone pictures, it slowly snowballed. The platform recently turned into something significant when it enabled people to preorder my new book Tokyo Yokosuka, which eventually helped fund the production cost. It is also a way for outtakes from my archive to be out in the world. I don’t know what I’m gonna post each day, so it’s like an odd, unplanned part of the day.

These days, we can’t help but feel nostalgic looking at photos of places. We can’t come back to the same place either because it has changed beyond recognition, or because of the prolonged travel restrictions. How do you feel looking at your own archive?

There’s a vast number of pictures from my magazine days that I haven’t looked at. I used to shoot business stories, conflicts, natural disasters, celebrity portraits, among other things – the general news photographer is now almost a thing of the past. On one hand, I have little interest in looking at them because I have forgotten about these assignments. On the other hand, when I do look at them, it’s not nostalgia, it’s the recognition of a life I no longer lead. I don’t have the connection to them anymore, so in a way, it’s like looking at found photographs.

The more interesting material for me might be the ones I took of Vancouver before becoming professional, which were more considerate, more personal, and more revealing of a place. I have to go through mountains of unedited slides and yellow Kodak boxes to find something, sometimes I never do, and I’ll probably never get to the bottom of that pile. It’s like a treasure hunt where I’m unsure of the reward.

Greg Girard is a Canadian photographer whose work examines the social and physical transformations in Asia’s largest cities for more than three decades. Based in Shanghai between 1998 and 2011, his photographic monograph, Phantom Shanghai looks at the rapid and at times violent transition of Shanghai as the city raced to make itself “modern again” at the beginning of the 21st century. Other titles include Hanoi Calling, In the Near Distance, and Hotel Okinawa.

Girard’s work is in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, The Art Gallery of Ontario, the Vancouver Art Gallery and other public and private collections. He is represented in Canada by Monte Clark Gallery.