[Matca] In an interview with Escapology, you discussed your photograph “Best Friends” stating that “On the way back, just by chance, I came across this scene which became my most popular photograph. A huge elephant, accompanied by this little girl, Kim Luan, of the M’Nong tribe. I approached very slowly and started taking pictures. The light was not very good during this time of the day, I had to hurry, but the scene was magical …. The other thing is, that members of the M’Nong hardly wear their traditional dresses anymore but Kim that day did which made the picture even more special…” Can you provide your account of how you took this photograph?

[Réhahn] I came across a little girl and an elephant while taking photographs of Lak lake in the Central Highlands and saw an opportunity to capture a moment which would illustrate how elephants are an important part of M’nong culture. I knew that we could not take this photo without permission, so with the help of my Vietnamese friend we asked for consent from the little girl’s parents. They agreed and we took photographs under the observation of an elephant trainer. This picture was taken to illustrate the respect between the M’nong and the elephants of Dak Lak.

[Matca] A Vietnamese article, published in Lao Động newspaper, challenges the story of how “Best Friends” was staged. Reporter Nguyễn Huy Minh visited Lắk district in Đắk Lắk province while reporting for the newspaper and cited the following claims

1. Huỳnh Trung Luân, the director of the Center for Elephant Preservation in Đắk Lắk, claimed that he was unaware of a child named “Kim Luan” as the M’Nông people do not typically name their children using the Kinh people’s language. The journalist then identified the subject’s parents, and he said that they reacted with surprise to hear that their daughter’s name was “Kim Luan.” Her parents, the Ma Vượt family, said their daughter’s name was Y Cúc.

2. The journalist also writes that he interviewed local villagers who claimed to have witnessed the staging photograph. They claim that also the photograph was staged. This contradicts the claims that you “came across this scene while walking back“.

3. The journalist also said that he spoke directly to Y Cúc with her parents. He writes in the Lao Động article the following statement: “Y Cúc returned home. She looks thin and skinny, is dressed in messy clothing and has a shy face. I asked her ‘Do you love elephants?’ She answered, ‘Yes, I do.’ I asked “Are you afraid of elephants?” Answer: ‘Yes I am.” I sighed, if she is scared of an elephant, why did she get close to one? Mr. Đức [Bùi Văn Đức, the Chairman of the Tourism Cooperative of Jun Village] talked more with the parents, whose name is Ma Vượt, and said that they [the photographer] borrowed traditional costume of the M’Nông people to put on the girl, asked her to stand close to the elephant for a picture with the quản tượng [elephant trainer] standing close by, to use for tourism advertisement imagery.”

Reporter Nguyễn Huy Minh’s claims suggest the photo was staged and contradict your published accounts. Matca recognizes that these are serious allegations. How do you reconcile these contradicting accounts?

[Réhahn]

1. I cannot comment on how the M’nong usually do or do not name their children. All I know is that the girl was introduced to me as Kim Luan and I have always called her that. I only learned her real M’nong name two years after taking my photograph Best Friends. However, her real M’nong name is actually H’Cúc Teh, not Y Cúc, as suggested by your source. If I had known her M’nong name at the time of course I would have used it and it does actually appear in my new book The Collection.

Her parents names are Y’Mik Buon Krong (father) and H’Bem Teh (mother). I wonder if your journalist was talking to the right family.

2. I cannot explain this claim. I am sure that apart from the elephant trainer and the little girl, there were no other locals around. The only time they would’ve seen me is when we went to the village prior to taking my pictures, to ask permission from the parents of H Cúc Teh.

3. Again I cannot comment on this reporters claims, all I know is that when I met H Cúc Teh and the elephant, she showed no signs of fear. What I can say is that when we went back to ask for permission to take the photo, this is when her mother put her into her traditional dress. I was very happy about this of course because I wanted to capture the beauty of the M’nong costume.

I recognize that in my Escapology interview suggests that I took this picture straight away. I hope that you can understand that English is not my first language and that at times I cannot express exactly what I want to say. This scene was real and I really did come across H Cúc Teh and the elephant while taking landscape pictures in the Central Highlands but of course the best-selling picture was not taken until we had first asked permission, had spoken to an elephant trainer and had put H Cúc Teh in her traditional dress.

[Matca’s responses] In addition to the Escapology interview, Réhahn’s website presents another conflicting account of the story behind the photograph (taken October 15, 2017).

Regarding the subject’s name, Réhahn’s photograph was taken in October 2014 and the above statement says he learned his subject’s name “two years later”. The gallery was opened on December 29 2016. As of October 15 2017, why do all gallery texts refer to the subject in this image as “Kim Luan”?

[Matca] Your philosophy is to preserve and to promote the cultures of minority ethnic communities in Vietnam that “might soon be lost forever.” What data sources do you use to backup the claims that the culture of these ethnic groups may be “lost forever” apart from anecdotal observation? Are you working with any local experts such as anthropologists, economists, or sociologists to learn more about cultural degradation across these communities?

[Réhahn] I have been travelling around Vietnam for almost six years photographing landscapes, light and people. People are what I find most interesting. I am lucky enough to have a Vietnamese friend who accompanies me on my travels and helps me to communicate with local ethnic people. Over the course of my career, I have personally witnessed the loss of cultural heritage in many of the ethnic minorities I have photographed. I have built great relationships with some of my models and would consider many of them my close friends. Sometimes when I return to a village to visit them, even one or two years later, much will have changed. Sometimes I will go to visit a tribe and they will all be in traditional dress and then two years later they have sold these costumes and are wearing something more modern. I like to ask these people directly about how their lives are changing. I am obviously not an anthropologist, economist or sociologist, however, for the most part I like to get my information directly from my models because their opinions are most important to me. I ask them about their music, their costumes and their lives and I have more than twelve interviews with them on video. I am not pretending to be an expert on Vietnamese ethnic culture, I am just a photographer who has fallen in love with Vietnam and has decided to dedicate my life’s work to capturing images of the people and places that inspire me and bring me joy.

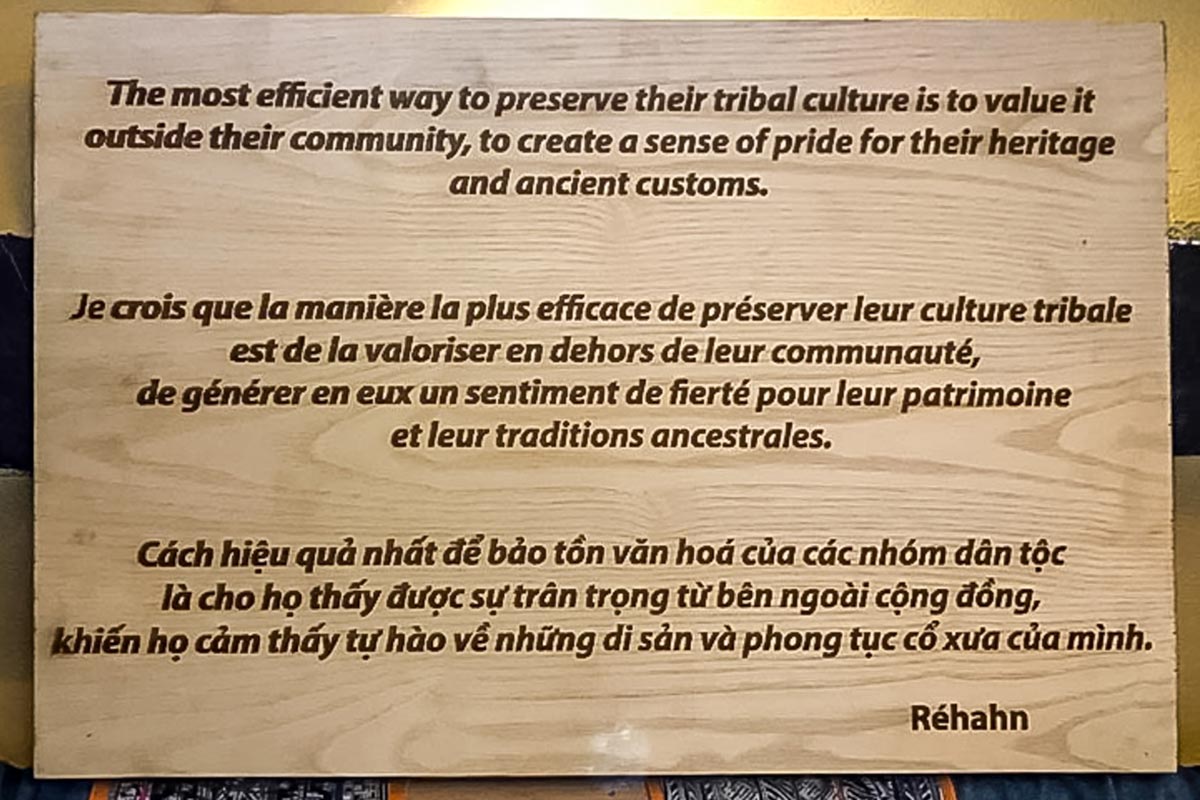

[Matca’s response] A placard at the entrance to the Precious Heritage Museum, as of October 15 2017, reads the following: “the most efficient way to preserve their tribal culture is to value it outside their community, to create a sense of pride for their heritage and ancient customs.”

The above text highlights how Precious Heritage Gallery and Museum are framed as sites of cultural preservation, in addition to hosting an art gallery. Further, the gallery and museum describe Rehahn’s work as “documentating” and cite his “research”. Is the role of Réhahn “just a photographer” here?

[Matca] In your book Vietnam: Mosaic of Contrasts VOL II, many of your subjects are women and children from “the most secluded mountains and villages”. How did you establish relationships with these communities? It is also written that “The children with such pure and innocent face, the elders with their wrinkle face, rough hands are what Réhahn wants everyone to see what so different about his view of Vietnam compare to the other photographers.” What do you think about such representations done by other photographers? Which other photographers are you referring to specifically?

[Réhahn] I establish relationships by talking to people, joking with them, drinking tea and listening to their stories. I take my bike and I go and see them. I build normal human connections when I visit these groups. Sometimes language is a problem but I am lucky enough to have a great Vietnamese team working with me to make communication a little easier.

I do not wish to speak publicly or criticize any other photographers. I will leave that to the art and photography critics.

[Matca] How do you receive ethical consent from subjects, especially children? (1)?

[Réhahn] I always ask permission when I can. I always share the photos I have taken with my models and normally get a great response. Usually, people are flattered to be photographed. It is always in my best interest to find the parents before photographing a child, it makes me, the parents and the child more comfortable and allows me to take better pictures.

[Matca] Your website explains the Giving Back project in the context of Karma. The “circle” is as follows: you take a photo of a subject, sell the images of the subject, and later, return to the subject to provide material help. The circle is “opened” and then “closed.” You describe the giving back process as a “circle” that is completed. Yet, after the “circle” is “closed,” you retain the rights to the images and can continue to profit from the sales. In this context, when does the circle “close”?

[Réhahn] The Giving Back Project is my way of helping and contributing to the improvement of my models standard of living. The circle is a metaphor. When I take a photograph of someone and when I am faced directly by their poverty I feel inclined to help. I can use some of the revenues from my work to positively impact the lives of the people I have met. So far I have paid for tuition fees, cows, travel expenses, a boat and even a funeral. I like to ask my models what they need and then give them that. You will notice that most of these things provide long term, sustainable benefits. Additionally, entry into my Precious Heritage Museum is free, so everyone can enjoy the costumes and artifacts that these ethnic groups have gifted me. It is by selling my images that I can raise money to continue the Giving Back project and to keep my museum free for all.

[Matca] In her article, Ha points to the iSEE as an organization that uses photography to “give back” to minority communities through empowering individuals to tell their stories. How do you respond to this model of cultural preservation? How do you compare your actual approach, in which an outsider dictates what is being shown, to iSEE’s approach, in which community members have the autonomy to decide what is shown?

[Réhahn] There is more than one way to help people. I appreciate any organization who is trying to help ethnic people in Vietnam. I do not claim that my model of giving back is perfect but I do what I can. I have actually been planning to donate cameras to an orphanage in Buon Ma Thuot for some time now, I think it’s a great idea. Thank you for bringing the iSEE project it to my attention.

[Matca] Ha Dao’s piece cites criticism of Steve McCurry’s work. In a piece for the New York Times, “A Too Perfect Picture,” art critic Teju Cole writes the following: “How do we know when a photographer caters to life and not to some previous prejudice? One clue is when the picture evades compositional cliche. But there is also the question of what the photograph is for, what role it plays within the economic circulation of images.” How do you think your work contributes to the economic circulation of images about Vietnam?

[Réhahn] I am not familiar with the term ‘economic circulation of images’ or any other economic theories. I will finish by saying that there are many sides to Vietnam. I cannot photograph and show everything, this is not my aim. What I show is my experience of Vietnam. Photography is vast and it is subjective, it is art and you are free to interpret my art however you see fit. This does not mean that your interpretation aligns with mine.

I would like to thank you directly for the opportunity to respond to your article. I am affected when I see the culture of so many people I have met disappearing. I am just a photographer who fell in love with this country who is trying to explore, capture and help.

(1) Matca defines ethical consent from children as meeting all conditions of UNICEF’s published framework: “Ethical Guidelines: Principles for Ethical Reporting on Children”.

*This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Dat Vu is a Vietnamese born photographer. He received his BA from Wesleyan University in 2015. Currently he is living and working in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam for a year as a Mortimer Hays-Brandeis Traveling Fellow.

Follow him on Facebook and Instagram..

Dorothy Lutz is an American based in Da Nang, Vietnam working in foreign policy and can be reached at lutz.dorothy@gmail.com.