Without much media coverage, the photography exhibition Second Opinion at Manzi Art Space has attracted over 2000 viewers last December. For a month, it showcased 8 projects made during the long-term workshop led by artist Jamie Maxtone-Graham at Hanoi Doclab. Like the title taken from a medical term, Second Opinion is a re-examination of private spaces by another group of young authors, a follow-up of Autopsy of Days exhibition in 2013.

Second Opinion does not follow a particular theme. This reflects the open approach in the three-month workshop: each student is encouraged to purchase a topic meaningful to themselves and a compatible approach to images. As a result, the works we see are of private matters and embedded with each artist’s personal vision. They offer different possibilities of photography while at the same time prompt to challenge the medium itself.

In the first work named Story of Blue and Red, Nguyen Thi Hue uses color drops moving in water to tell a story about her relationship with her parents. The artist shared that she soon became dissatisfied with straightforward portraits she took at the beginning, so she decided to use color to elicit emotions hard to see with the naked eye. The work needs no long description; its meaning is largely based on the audience’s intuitive feelings when faced with colors and motions. Another World by Hanh Tran is also highly abstract; she uses a negative filter to transform small objects like seashells, wild grass or wooden floors into the mighty galaxy.

The installation is particularly effective in some cases. Ha Dao’s visualization of tension in a romantic relationship is separated into four groups of photos, revolving around the only image where two people can be seen together. The author’s portraits are placed on the opposite side of her girlfriend’s, as if they are looking at each other and reflecting on one another’s loss. The theme of young love and heartbreak also appear in Le Xuan Tien’s work on the second floor, but the imagery is more vague and metaphorical.

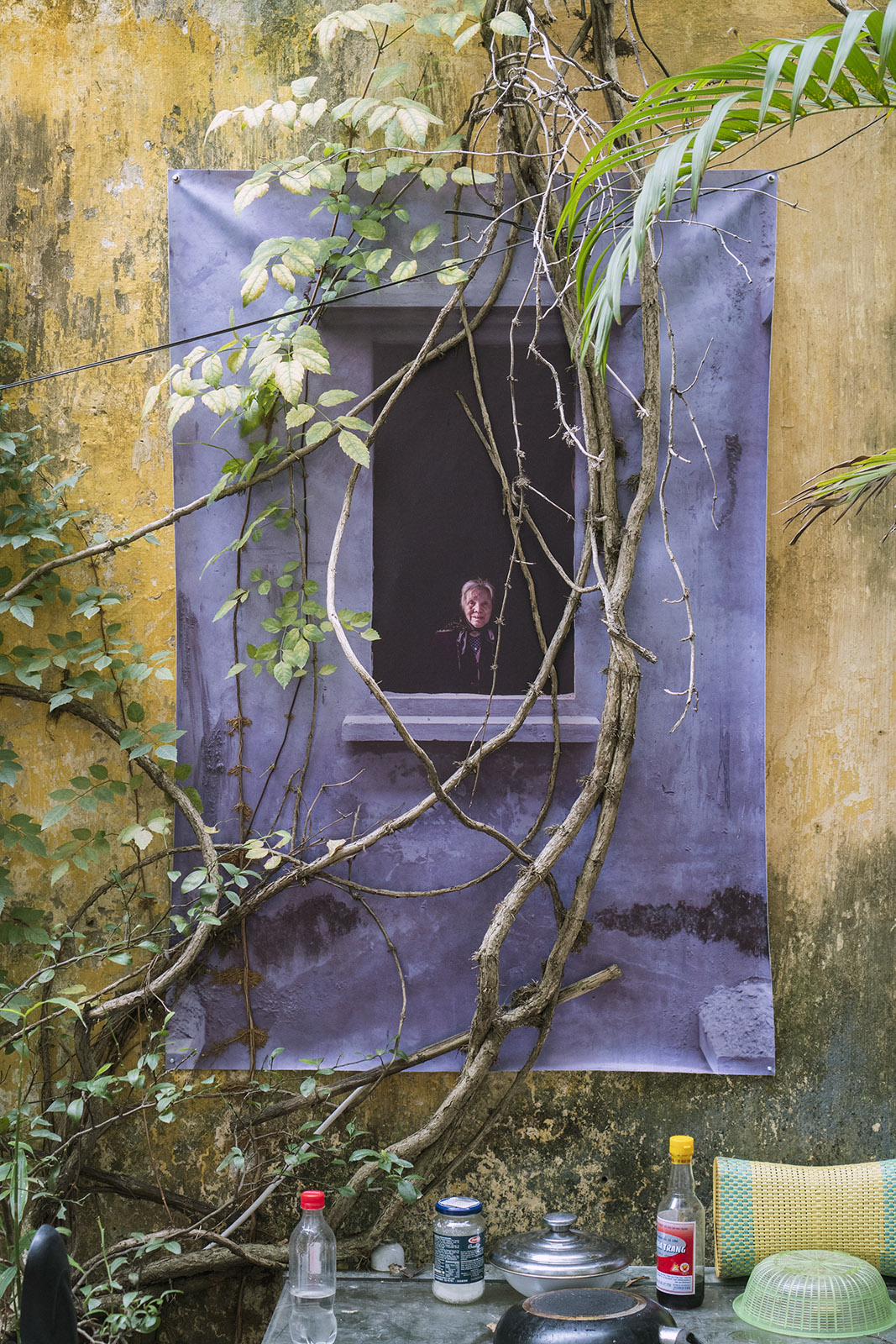

From the windows of Manzi’s first floor, viewers are confronted by the haunting portraits of Duong Noi residents who seem to be either judging or waiting for onlookers. Walking to the side alley to get closer to the work, we will come across more photos on the back of the building. This project has been shared on the Facebook page Chuyen Cua Thinh (Thinh’s Stories), yet how it is hung has added another layer of meaning. The photos blend in with the space, implying that people on the margins of the society, despite being paid less attention, still quietly exist.

The series Mom-me by Viet Vu is hung along the staircase and can be viewed both ways. These are no ordinary pictures about maternal love. The series itself can be considered as a psychological test, since it evokes different reactions from the audience based on their own experiences and standpoints.

At the center of dream-like scenes of an elderly woman in the countryside are two nude photos of herself and the author. Viet Vu shares that he has photographed her as a son photographing his mother, rather than a photographer and a subject. While making the work, he keeps coming back to the question of how to get closest to this person, and nude photos are the only satisfactory answer. The mother’s body imprinted with traces of time becomes a proxy for Viet to enter her inner world, to search for and mend the cracks, and to tighten the already visible connections.

Walking through the gallery on the second floor, viewers will see the last two works that have a much different feel than those emotional pieces downstairs. Taking the whole wall the 4-square meter large piece 112 by Nguyen Duc Huy, recording the gradual rotting process of tangerines. The gradient effect from bright orange to dark grey compels the audience into the passage of time laid in front of their eyes with the question posed by the author: At which moment do the tangerines die? Whether coincidental or purposeful, Huy’s work also question fundamental attributes of photography like time and death.

Mai Pham presents a new kind of street photography. At first glance the images seem to be of random scenes, but look closely and quite a few easter eggs can be discovered inside each busy frames. Not chasing after the decisive moment or the golden light often seen in street photography, Mai depicts Hanoi as a living organism that contains within itself motions and conflicts; a city set to reach prosperity and modernity yet fails to shake off old customs.

Second Opinion affirms the willingness to take risk and experiment new directions of those who have just begun their artistic journey. This also poses not small a challenge to Jamie Maxtone-Graham throughout the three-month workshop. “My challenge as an instructor is to understand what each person is going through and help each one connect to the central idea of their own work. Because it’s all brand new and confusing, it is easy to feel lost and uncomfortable and my challenge is to help people understand that it is right in this place of discomfort that the greatest learning happens.” In Second Opinion, the young authors have somehow explored their relationships with life and photography, a tool that helps them explore, reflect, express, connect and tell their own stories, from which they can open the door to other realities.