This article originally appeared on Trans Asia Photography Review and is reposted with permission from the author Thy Phu.

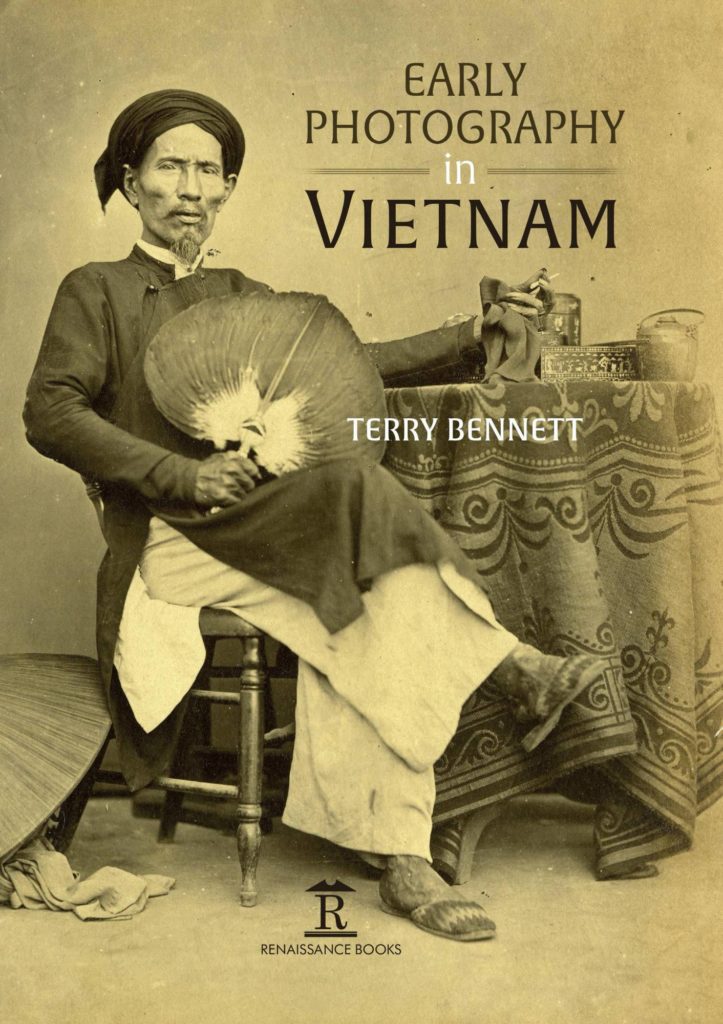

There is a growing demand among scholars for a history of Vietnamese photography — a study that might provide insights into such intriguing questions as: What does Vietnamese photography look like? For whom are Vietnamese photographs made, where do they circulate, and what are their meanings? From a visual and conceptual perspective, how did Vietnamese photography evolve over time? In what ways did Vietnamese photography intersect with global trends in photographic practice and how did it differ from them? Terry Bennett’s Early Photography in Vietnam is not this book.

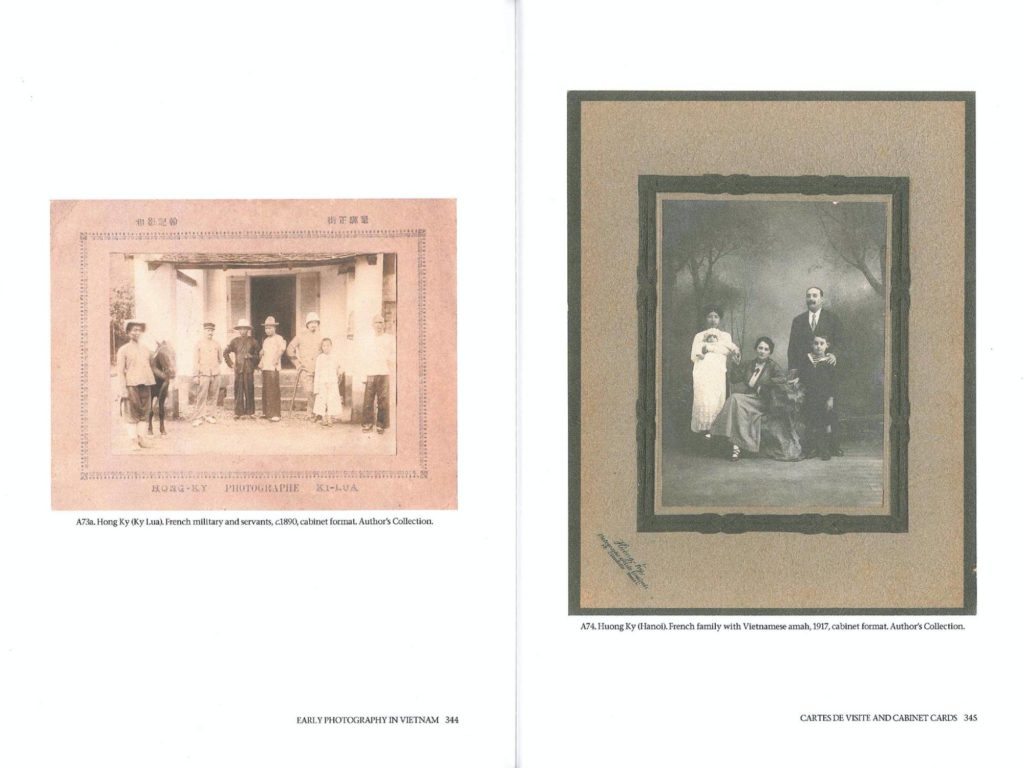

Instead, Early Photography in Vietnam pursues a different set of questions, among them: Who are the earliest and most important photographers operating in Vietnam during the French colonial period? and What images did these photographers make and when? Bennett, a photo-enthusiast and avid collector of Asian photography, offers, as he puts it, a “modest” contribution to the field. His book’s title announces the chronological scope of his survey, which centers on photographers who worked in Vietnam during the period of French colonialism, from 1845 to 1955. To provide what, by his own admission, is a selective overview, Bennett employs resourceful and creative methods, which include consulting colonial archives and gleaning clues from hobbyist websites. These methods enable him to tell a story about the emergence and development of a thriving industry of commercial photography in Vietnam, one that draws largely from material from his own private collection in addition to photographs from archival special collections.

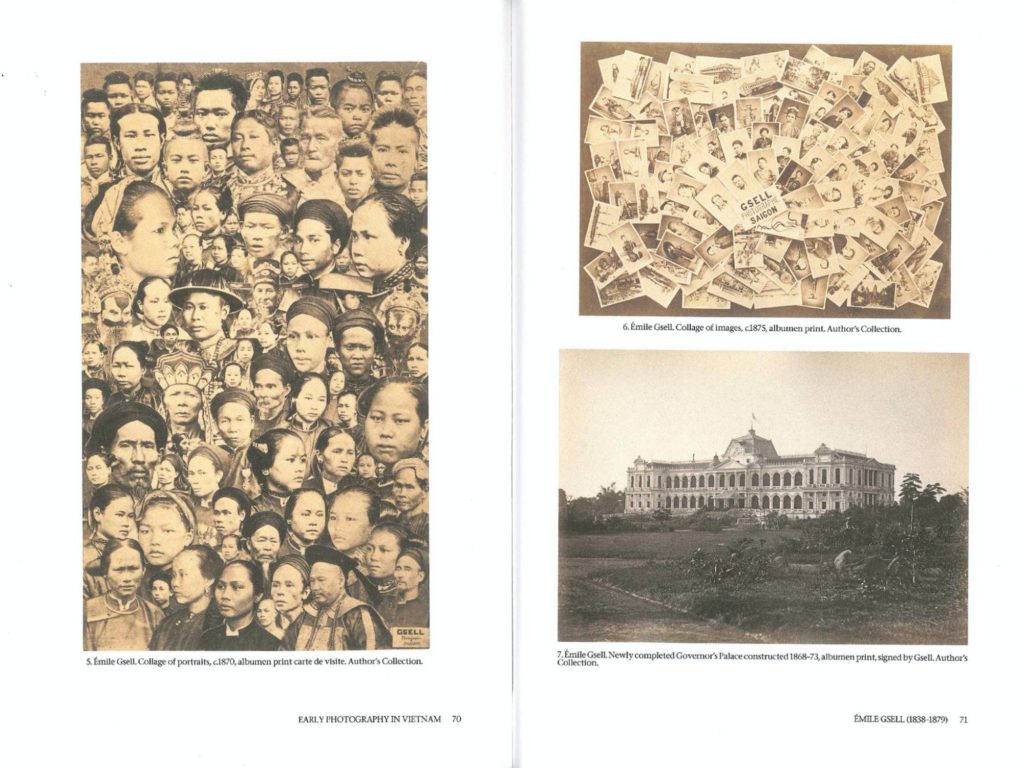

In six chronologically organized chapters, the book sketches the colonial context: the work of prominent photographers — mostly French — whose travels in Asia, as either adventurers or colonial soldiers or both at once, eventually brought them to Vietnam, where they set up shop. Chief among them are French photographers Émile Gsell and Charles-Édouard Hocquard, who receive their own separate chapters, a sign of their elevated stature. Given the dearth of knowledge about this period of photography history, not to mention photography’s role in this region, Bennett’s research provides a useful starting point for further inquiry, which is one of his primary objectives.

A major weakness of the book, however, stems from the sources that Bennett employs. By combing through French colonial archives and relying on those who served the ends of empire, the book ends up advancing, however unintentionally, a colonial way of seeing. Although these sources are valuable, the book suffers from a lack of Vietnamese perspectives, despite Bennett’s uneven efforts to include a list Vietnamese studios, such as those operated by Đặng Huy Trứ, Pun Ky, and Trýõng Vãn San, in his catalog of early photography. This can also be seen in the manner in which French perspectives are demonstrated, with accents fully represented, especially when it comes to proper names. In contrast, Vietnamese words and proper names are not rendered with similar care: Diacritics that denote tones crucial to meaning in the language are omitted. The omission of diacritics is a standard practice, ostensibly meant to streamline typography, but recent scholars in Vietnamese studies have drawn attention to its implications in obscuring the specificities of language. (Recognizing these important developments in engaging with the subject of Vietnamese culture, this review attempts to use diacritics for proper names.) Readers are left with an obvious message about whose point of view is prioritized.

Indeed, material in colonial archives and colonial-period photos that dominate the contemporary art market tend to be privileged as source material in putting together early photo history. It is apparent that Bennett’s book is not about Vietnamese photography. Nor is it about Vietnamese photographers. Nor for that matter, I would argue, is it for Vietnamese viewers.

To be clear, colonial archives should not be disregarded; they are useful in understanding, for example, the ways that colonialism facilitated early photo practice and that colonial imagery was privileged in official archives and framed ways of seeing and knowing Vietnam and the Vietnamese. Moreover, one can argue that those are the images that usually are readily available so they are all we have to recover a history of early Vietnamese photography. However, the book seems to overlook a now familiar and respected critical practice of reading against the grain, of using archives as discursive rather than factual representations of the past. Indeed, material in colonial archives and colonial-period photos that dominate the contemporary art market tend to be privileged as source material in putting together early photo history. It is apparent that Bennett’s book is not about Vietnamese photography. Nor is it about Vietnamese photographers. Nor for that matter, I would argue, is it for Vietnamese viewers.

At the outset, Bennett writes that his objective is a descriptive overview of early photography in Vietnam and not an analysis of colonialism. In addition, in the preface Bennett scorns those he describes as “postcolonial” scholars, whom he criticizes for their preoccupation with “the imperial gaze.” Such a preoccupation with the imperial gaze, he contends, is irrelevant for early photography in Vietnam because it disregards the fact that photographers were principally interested in establishing profitable businesses. Bennett’s dismissal of postcolonial critique is not only willfully short-sighted but also blithely ignorant of decades of work that persuasively establishes the complex intertwining of commerce, aesthetics, and power. Indeed, Bennett’s strident dismissal of an analysis of colonialism leaves an incomplete story given that photography is inseparable from the colonial conditions that facilitated it. As Ariella Azoulay provocatively contends in Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso, 2019), photography’s origins go back to the violent colonial encounter of 1492, so any discussion of photography’s earliest period that neglects to seriously grapple with colonialism is woefully incomplete.

Bennett’s hostility to this form of critique is telling, for it reveals the book’s own attachment to a photographic marketplace, which results in further holes in the overall narrative. For example, even when the book attends to Vietnamese photographers such as Võ An Ninh, Bennett’s focus on commercial photography leads him to neglect Ninh’s greater achievement in documenting the devastating 1944–45 famine, caused in part by corrupt French land-administration policies in the wake of the Japanese occupation of Vietnam during WWII. For that matter, it’s not clear why Bennett should focus on commercial photography; he neglects to explain his rationale, instead seeming to take for granted the inherent interest this genre would attract over other genres. And yet, without this explanation, readers might well wonder about the nature of Bennett’s own interest in the topic, given his investment in — as a private collector of — commercial photography in Vietnam, and Asia more broadly.

It is hardly surprising, then, that Bennett’s latest book is an extension of his earlier projects, indulging as it does in biography, or rather hagiography, as one reviewer aptly puts it, in response to his work on China.[1] Significantly, then, the chronological structure of the book serves as background, even at times as picturesque backdrop, for lavish illustration of beautiful images of Vietnam. In this way, contextualizing information functions not as a means of historicizing images but instead, it seems, to provide provenance for them. That is, chronology offers less a methodology and more an expedient means for Bennett to lay out who came before whom, which images were made when.

This leads us back to the book’s primary limitation: namely, its acknowledgment of colonialism as a context in which photography in Vietnam develops only to foreclose consideration of the impact of this context. For example, a background chapter elucidating French colonization of Vietnam seems simply to serve as a set piece against which hagiographic consideration of European photographers unfolds, as if the two are only tangentially connected. Consider the opening chapter, promisingly titled “Colonialism and the Camera,” which relays the ostensible facts of French colonialism without delivering on how this exercise of power and domination relates to the camera. While Bennett asserts this is not what his book is about, his desire to disentangle them explains why, even when he appears to pair colonialism and the camera, he demonstrates his palpable lack of concern with their connection. Notably, some of the photographers whom Bennett praises as early practitioners of the art — including Émile Gsell — arrived in Vietnam precisely because they enlisted as colonial soldiers; indeed, they learned how to photograph as a consequence of their military service. Others, like Clément Gillet, enjoyed close connections with officers, which enabled them to accompany the military on operations in Vietnam. It is hardly coincidental, then, that the subject of some of these photographs is the colonial exercise of military power.

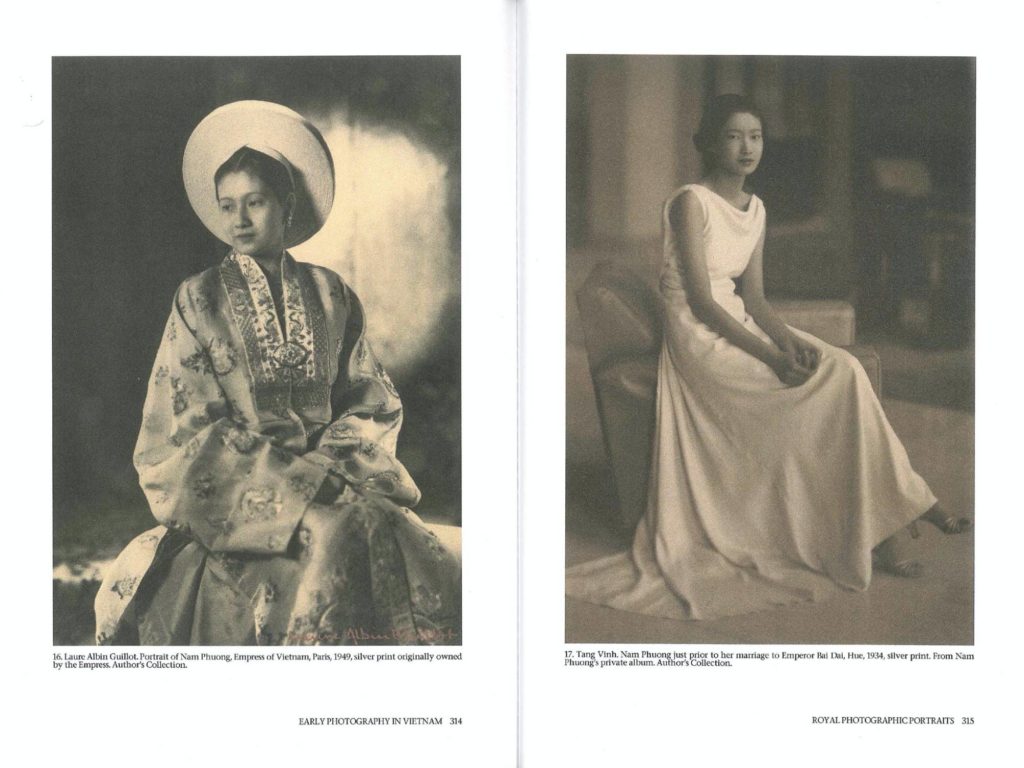

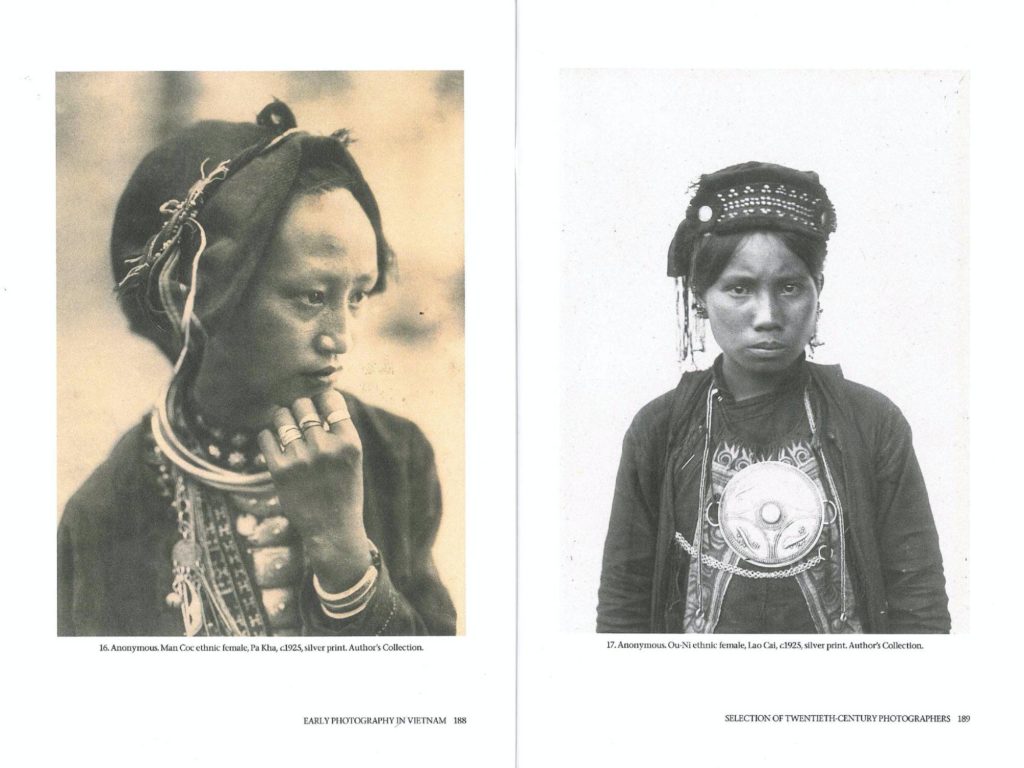

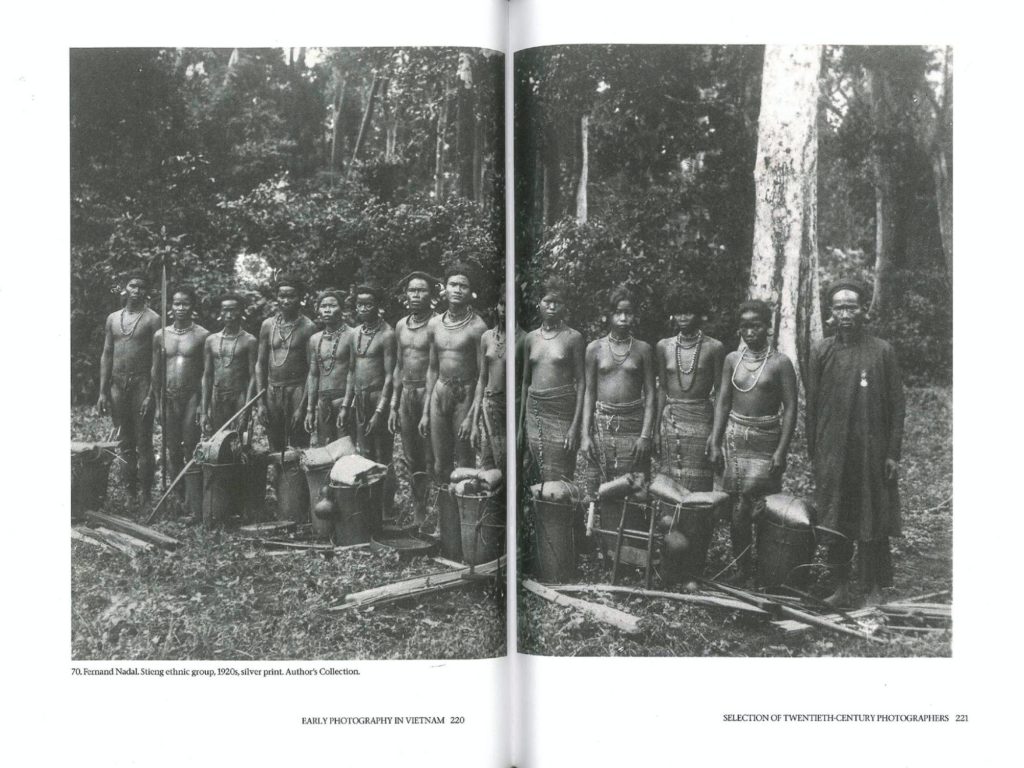

Given this context, not to mention the unmistakable content of the images, Bennett’s rejection of the “imperial eye” as a lens through which to view early photography in Vietnam seems naive if not self-serving. The framework of his book — simultaneously an admission and a denial of colonialism’s connection to photography — fails to be convincing. In considering Bennett’s oeuvre, which includes a number of books on photography in Japan and a three-volume set on photography in China (2009, 2010, 2013),[2] one cannot help but notice that the author’s collecting practices uncannily overlap with the photographers’ journeys, reproducing with neither acknowledgment nor critical reflection the photographers’ own preoccupation with producing what many viewers will surely recognize as familiar colonial tropes, from lush landscapes to naked “natives.” Once staples of ethnographic studies, here these images of otherness — presented without context or commentary — function as adornment in a similar way as when they were first made. And, one could argue, the images published in the book perpetuate the same violence of distortion and erasure on the individuals and communities depicted as the original images did.

One might ponder the workings of the camera as an instrument of capture and consider how the “native” who gazes into the lens might offer a visual statement, however equivocal, on this enterprise. These are considerations that Bennett himself evades and, indeed, preempts. For all its remarkable images, the book stands out more for its indifference to the ethnographic tropes that it uncritically reproduces. Just as important, the book disregards the ways that colonialism is thoroughly entangled within a photographic marketplace — as a process, in other words, that makes and unmakes photographic meaning. In the colonial period, photographers catered to an appetite for exploration, conquest, and subjugation. Yet these market forces seem inchoate and abstract, so quickly does the book shy away from the appetite for such images in France, their potential circulation as part of a visual economy of touristic consumption, or, for that matter, colonialism as an enterprise predicated on resource extraction, land expropriation, indigenous subjugation, and consumption of images of otherness. In the absence of any inquiry by Bennett of the very issues he raises through his invocation of colonialism, one is left wondering whether the book’s ultimate interest — the contemporary market for commercial photographs of early Vietnam — unsettlingly extends colonialism’s own market-driven desires.

Thy Phu is a Professor at Western University, in Canada. She is the author of Picturing Model Citizens: Civility in Asian American Visual Culture and Feeling Photography. She is currently completing three books, Warring Visions: Photography and Vietnam and Cold War Camera (both forthcoming from Duke University Press) and Refugee States: Humanitarian Exceptionalism and Critical Refugee Studies in Canada (under contract at the University of Toronto Press).