THIS ARTICLE IS SUPPORTED BY THE BRITISH COUNCIL AS PART OF THE UK/VIET NAM SEASON 2023

On their journey to the South, Vietnamese people had left their footprint on the names they gave to geographical locations. Place names originated from sounds, first uttered spontaneously by someone, then became widely accepted within a community before being formally written down via early Chinese and Sino-Vietnamese characters or modern Romanized script. Locations changed names several times across centuries; not all were recorded in scholarly works. Across the country, countless are the names of villages, mountains and rivers. Among them, the coastal rocks of Hòn Rái and Hòn Nghê with their picturesque landscapes and uncommon names are two landmarks that I long to visit one day.

Telling details can be revealed by studying the practice of naming places after animals. The book Fierce lions, angry mice and fat-tailed sheep: Animal encounters in the ancient Near East (2021) points out that numerous toponyms in the ancient Near East were associated with animal species inhabiting this region such as lion, mouse and sheep1. Findings on the complex interactions between animals, humans and their living environment make us look at animals in a different light and consider them as an integral part of various communities’ cultures. However, in some cases, animals came to be the name of lands where they had never set foot. For example, while lions are not native to Indochina, the first capital of the early Champa Kingdom was named Simhapura or Sinhapura, meaning the city of Lion. Similarly, despite being a mythological creature, dragons appear in various place names in Vietnam including Hạ Long (“descending dragon”), Bái Tử Long (“dragon offsprings bowing to their mother”), or Long An (“the peaceful land of the dragon”).

Toponymic research can offer profound insights into the history of a place, including settlement, migration, religious practices and linguistic changes, as indicated in the Encyclopedia Britannica. In Vietnam however, research on geographic names remains a largely uncharted territory and hardly practiced as a scientific discipline. A study of Vietnamese ancient place names can be found in Vũ Trung Tùy Bút (Written on Rainy Days), a collection of chronicles by scholar Phạm Đình Hổ in the late 18th-early 19th century; yet it provides no remark about animal names.

The story of Hòn Rái

The coastal rock named Hòn Rái, alternatively Hòn Sơn Rái, is intimately tied to the cultural ecology, specifically the coastal culture of the early Vietnamese people. Along our seashore, various scenic locations bear the name of “rái” (otter), including Gành Rái bay in Vũng Tàu, Hang Rái cave in Ninh Thuận, allegedly once home to many otters, and Hòn Rái in Kiên Giang, renowned for its story of the otter that saved the king. Legend has it that during the Vietnam Civil War in the late 18th century, Prince Nguyễn Ánh took refuge in Hòn Sơn island while being pursued by the Tây Sơn army. An otter brought him seafood, saving him from starving to death. After his coronation, Nguyễn Ánh granted the otter the honorable title of Second Great General and baptized the island Hòn Sơn “Rái”. Nowadays, multiple otter species inhabit coastal banks from Liaoning in northern China through Fujian, Guangzhou to Vietnam and Indonesia. However, their population has been on steady decline due to climate change and illegal trade. In Vietnam, otters are protected in the mangrove forest of Bái Tử Long National Park, Quảng Ninh.

Otters make frequent appearances in Đông Sơn art of ancient Viet people, who used to live along the coastal zone hosting various otter species. Their Đông Sơn bronze drums represent otters in several stylized figures, with simplistic contours that nevertheless capture the animal’s essential features. An amphibious species living in both fresh and salt water bodies, otters are known as excellent fish-hunters. People of Đông Sơn culture, whose life was deeply rooted in the Red River Delta, dreamed of being as skilled in swimming and catching fish as the otter. This mindset is reflected in the idiom “Blessed are those whose child swims, cursed are those whose child climbs”. Ethnologist Tạ Đức has developed the idea that the otter was elevated into a totem in Đông Sơn culture2. Though this theory remains debated, otters remain widely revered by Vietnamese people. Also according to Tạ Đức, the name Yết Kiêu–a naval general with remarkable aptitude for swimming–might also hint at the otter, as it denotes a type of hunting dog according to the ancient Chinese glossary Erya, and otters are sometimes referred to as water dogs.

Emperor Đinh Tiên Hoàng (924–979), also a national hero praised for his talents in swimming and diving, is said to have been sired by an otter. Chinese ethnologist Zhong Jingwen has pointed out an intriguing similarity between legends about the births of Đinh Tiên Hoàng, the Emperor Taizu of Song (927–976) and the Emperor Taizu of Qing (1559–1626) in China, since they all involve the motif of miraculous conception from an otter3. The story might seem hardly plausible to Confucian historiographers, yet it was recorded in a collection of writings by Confucian mandarin Vũ Phương Đề in the 18th century. The myth surrounding the Emperor’s otter parent demonstrates how otter worship is firmly entrenched in the spiritual life of Vietnamese people even after 1000 years of Chinese rule. Sea creatures motifs were revived on the nine Tripod Cauldrons in Huế Imperial Palace during the Nguyễn period, demonstrating our enduring maritime heritage, but regretfully, the otter is absent from these depictions.

The Story of Hòn Nghê

Located east of Sơn Trà Peninsula, Hòn Nghê or Mũi Nghê (Nghê coastal rock or Nghê cape) is renowned for offering the most spectacular sunrise in Đà Nẵng. The name perhaps originated from the topographical resemblance with a nghê reaching out to the sea, its head facing the cliff. The first people who came across this spot must have exclaimed, That’s a nghê. But what is a nghê, and why did our ancestors name the cape after this animal?

Nghê is a mythical animal inspired by lions, or more precisely, sacred lions in olden days. Confucian scholar Huỳnh Tịnh Của gave a definition in the first Vietnamese dictionary Dictionnaire annamite (1895-1896): “Nghê, a lion-like creature”. It was mentioned in the ancient Chinese glossary Erya as suānní 狻猊, a “devourer of tigers and leopards”.

But nghê was not an invention of ancient Han Chinese people. The term mentioned in the Erya is possibly of Indo-Iranian origin. It may have derived from /suangi/ in Old Indian languages, then /sarvanai/ in Scythian, a historical language spoken in Central Asia. The book Korean Theatre: From Rituals to the Avant-Garde (2015) traced the origin of the traditional Korean lion dance to West Asia or India: “Sanye, a lion dance of western Asian or Indian origin, was most likely performed to promote the spread of Buddhism since the lion is often symbolically associated with Buddhism in Asia. Many people from Asia believe this fierce animal allegorically represents either the servant of Buddha or the living image of Buddha himself.”4

Huilin, a Buddhist monk in the Tang dynasty in China, once said: suānní is a lion from the Western Regions. The Chinese rhymed prose “Fu on the Lion” described holy lions as wild beasts living south of the Kunlun Mountains. These interpretations partly explain physical similarities between lions and nghê. They also serve as a compelling indicator of the seemingly distant relationships among India, Central Asia and ancient Vietnam.

When initially introduced to Vietnam from the Western Regions in the early centuries AD, nghê had rather ferocious features. After being adopted in Buddhist shrines, it gradually transformed into a dog-like animal sitting at the feet of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. In Buddhist iconography, the Bodhisattva of wisdom Manjushri is often represented as riding on a nghê. In the Pala period (750–1611), the lion was metamorphosed into a dog, which perhaps explains the vernacular name Foo dog – the Buddhist dog. The term toan nghê (suānní) was contracted into one syllable in the Vietnamese language (ní), pronounced nghê [ŋe˧˧]. Inscriptions on the Minh Tịnh temple stele from the Lý dynasty (circa 1090) spoke of toan nghê, but the mononym nghê has been used since the Trần dynasty (1225–1400) onward.

From Buddhist spaces, nghê appeared in other places of worship, guarding communal houses, temples and shrines of historical figures and deities. It entered into folk poems and proverbs of the feudal era: “laugh like a nghê”, “the phoenix dances and the nghê attends court”. In Confucian temples, nghê are usually found flanking the entrances, as are the pairs of nghê sitting on two sides of the Đại Thành gate in the Temple of Literature in Hanoi. A mandarin and a nghê are said to share a similar fate as expressed in a poem by Confucian scholar and statesman Nguyễn Công Trứ, composed in reply to a prefect’s lament on his bureaucrat’s career5. The personification of nghê shows how the mythical animal represents Vietnamese people’s innermost thoughts and desires and conveys every facet of their emotional lives.

Globalization has led to growing Chinese and Western influence in Vietnam. The stone carving village in Marble Mountains Ngũ Hành Sơn swarms with lion statues modeled after Western and Chinese depictions. An artisan in the adjacent province once told the press that he had never heard of nghê. Yet, if nghê was not a common figure, then how might one explain the name Hòn Nghê at the Sơn Trà Peninsula nearby?

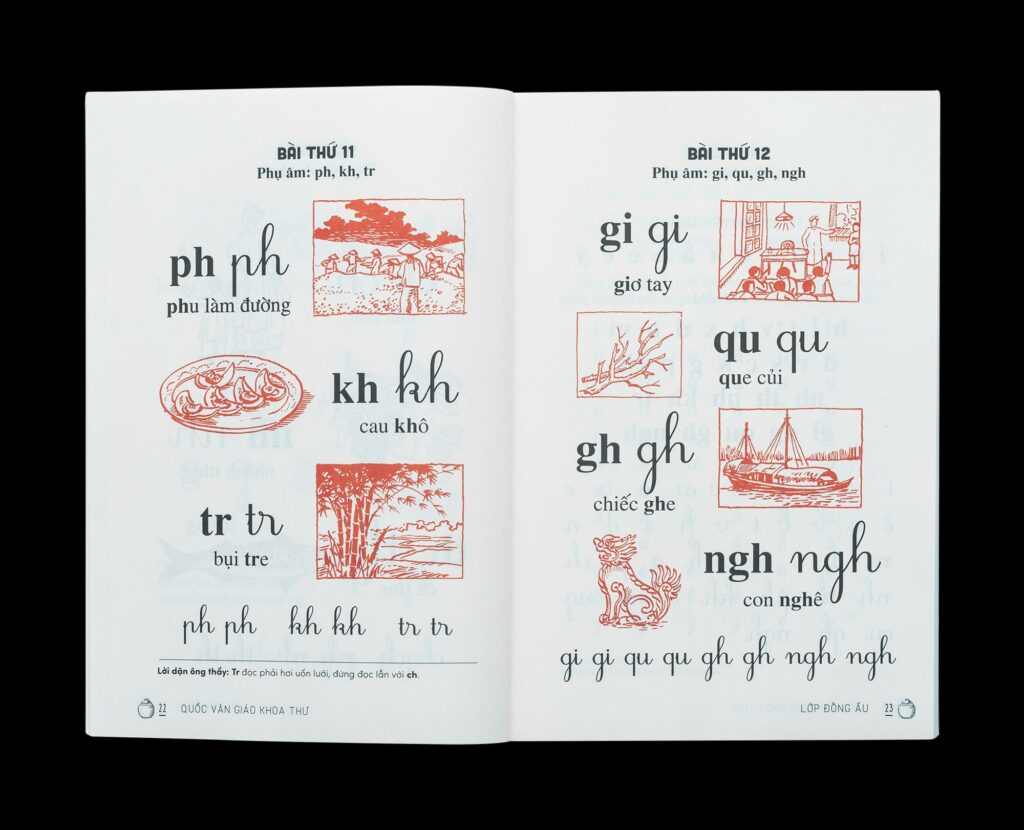

In Quốc văn giáo khoa thư, the first Vietnamese primary textbooks published in 1926, elements of national culture are incorporated into the illustration of each spelling lesson, offering a comprehensive outlook on Vietnamese society. The pronunciation of the morpheme ngh- /ŋ/ is exemplified by the drawing of a nghê at the front entrance of communal houses, temples and pagodas. By that time, most Vietnamese children were familiar with the omnipresent figures of nghê carved on village gates, temple pillars, pagoda roofs, offering tables, and sanctuaries of communal houses. A century later, nghê is still very much ever-present in Vietnam’s traditional architectural landscape. However, it has been removed from modern textbooks.

Epilogue

I remember fondly a time in my youth when, after walking alone at night through sand dunes, watermelon fields and cajuput forests, I finally reached the shore and took a refreshing nap while awaiting the first rays of sunlight. It was the first time in life when I woke up to sunrise at the sea. I have been longing to relive the same experience ever since in Hòn Nghê and Hòn Rái. Surely, the sun and the air might differ, but the familiarity of those monosyllabic names will fill me with tenderness all the same. Hòn Gai, Hòn Hòn Ngư, Hòn Rơm, Hòn Hèo, Hòn Nhạn, Hòn Thơm: scattered across the coastline of Vietnam are endearing place names inherited from the ancient civilization. These names, formed with only two or three syllables, reflect our inheritance from Chinese and Cham culture and the country’s long-lasting marine culture. All along the coast of Vietnam, mountains and rivers bear witness to major natural and geopolitical changes that shaped the nation. Place names might emanate from casual utterances, but they have been preserved through generations by a strong collective consciousness. Some may sound strange at first, as we have drifted far from our roots. It’s about time we found the way back.

1. Dirbas, Hekmat (2021). “Animal names in Semitic toponyms”. In L. Recht & Ch. Tsouparopoulou (eds.), Fierce lions, angry mice and fat-tailed sheep: Animal encounters in the ancient Near East. Cambridge, p.103-11.

2. Tạ Đức (2013), Nguồn gốc người Việt – người Mường (Origin of Việt and Mường Peoples), Intellectual Publishing House, Hà Nội.

3. According to Professor Kiều Thu Hoạch, Zhong Jingwen’s research on the birthplace of the legend of the otter’s son might have been the earliest comparative study of Vietnamese, Korean and Chinese folk literatures. In Vietnam, this work is archived in the Japanese collections of the Institute of Social Sciences Information, Hanoi.

4. Cho, Oh Kon (2015). Korean theatre: From rituals to the avant-garde. Fremont, California: Jain Publishing Company.

5. Nguyễn Viết Ngoạn (2002). Nguyễn Công Trứ, tác giả – tác phẩm – giai thoại, NXB Đại học Quốc gia TP. Hồ Chí Minh, tr.433.