Being a quarter Vietnamese through her grandfather without inheriting much of his cultural identity, Prune Phi has regretfully witnessed the vanishing of bodily features carrying her family history across each generation. Taking a plastic arts approach to photography, her work, at the crossroads of multiple mediums, attempts to grapple with complex issues of transmission, memory, and hybrid identity.

Since 2017, Phi sets out on a transcontinental quest to locate the missing parts of her personal history, which results in the two projects Long Distance Call and Appel Manqué (Missed Call). Participating in the Villa Saigon residency program in 2020, she seeks to complete Hang Up, the final chapter of this visual investigation in the country where she is partly rooted. It all started with a long-distance call to the relatives that she had never met.

From Southern France to America and now Vietnam, how did the search for your origins evolve?

I produced Long Distance Call during my first visit to the relatives on my grandfather’s side in America. The project deals with questions of cultural transmission and family heritage, including things that fail to be passed down or go unsaid. Since I faced difficulties communicating with older generations – there were secrets and taboos related to past traumas, I turned to my cousins, volunteered in youth associations and met with university students. This experience sparked my interest in the young generations, which continued to develop upon my return to France with the second project Appel Manqué. I wanted to explore how Vietnamese diasporic descendants apprehended their ancestral culture. The starting point was my own history, but as I encountered other young people and saw myself in their stories, I was able to retrieve some fragments of my identity.

I pursue this focus on youth in the last chapter, Hang Up. The title is inspired by a common line in teen movies, you know, there’s always a character who says “No, you hang up first”. I’d like to end on this note when we still have much more to share but it is time to hang up. What I like about the analogy to the telephone is distance: to call someone on the phone is to hear their voice, a way of being in their presence while maintaining a distance. It’s a special relation to the other person.

You create works using various mediums. How does photography fit into your practice?

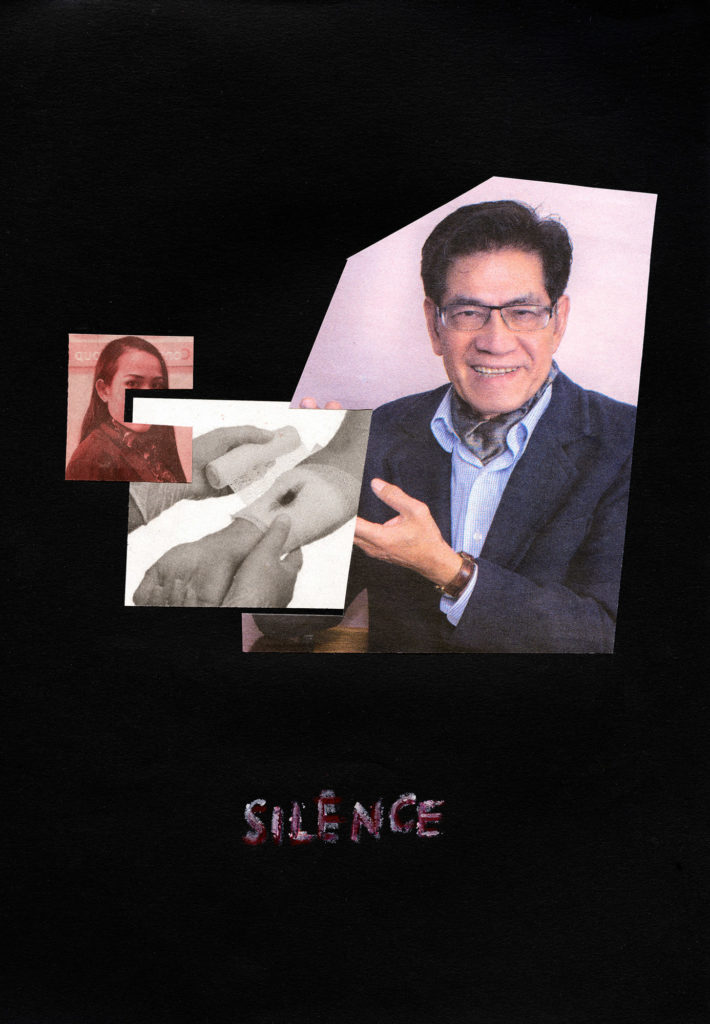

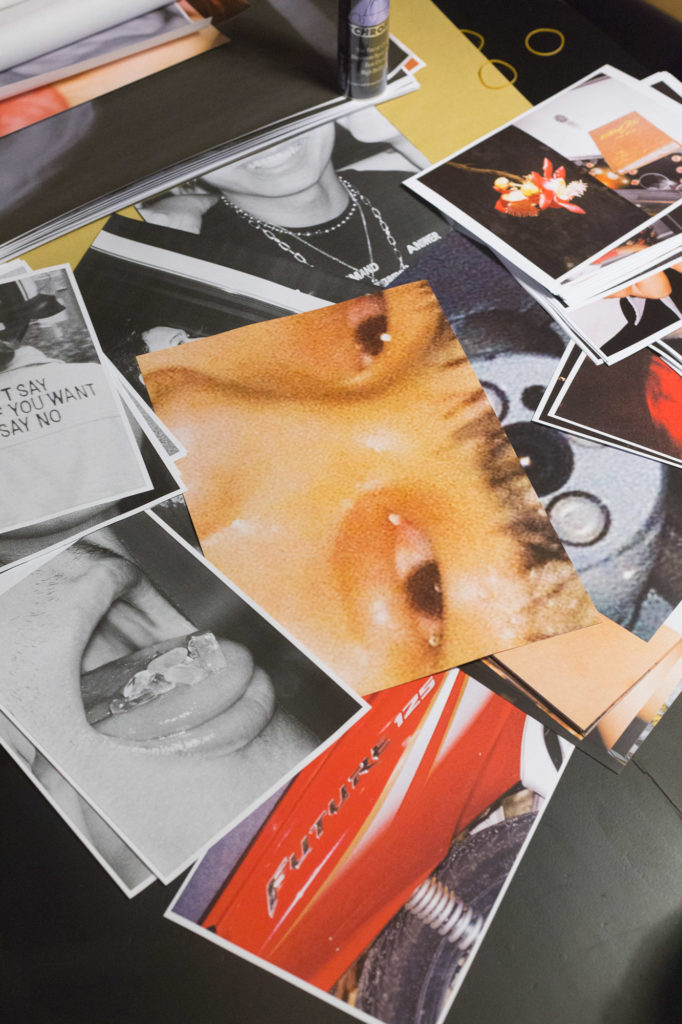

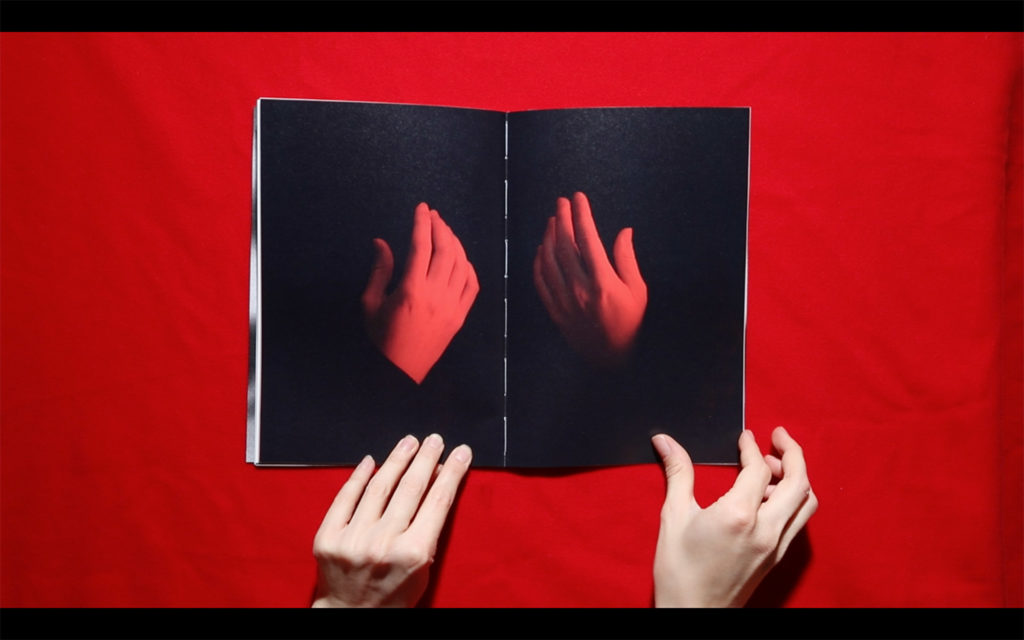

I use photography as a research tool, to collect and archive my observations, my experiences, and the encounters that I had. Taking photos is only the first step of the creative process. In my work, photos never appear in their entirety, to signify meaning per se: they are transformed, present as fragments within collages, associated with other materials to construct meanings. I think this approach to image is driven by the feeling of having multiple origins, and the need to find all the answers about different components of my identity.

In your collages, the photographic medium focuses on depicting body parts, in close-up or fragments, while the grayscale tone is reminiscent of medical images. Could you explain this emphasis on the body?

Since high school, I’ve been passionate about biology. This research on my origins began with questions of genetics. I also have a fascination with anatomical images. Combining fragments of images in collages is an attempt to understand how complex identities are constructed in the body, in the same way that anatomy studies the human body by dissecting it in various parts. I’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with scientists in vision, memory, and brain research for many projects, which definitely leaves a great impact on my approach.

I once met with a neurobiologist who spoke about the concept of false memories. In reality, memories constantly recombine and change over time, even drift toward fiction. I incorporate this aspect into my installations. I don’t want to tell the story in a similar manner from one year to the next, because the way I remember and consider it also differs as time goes by.

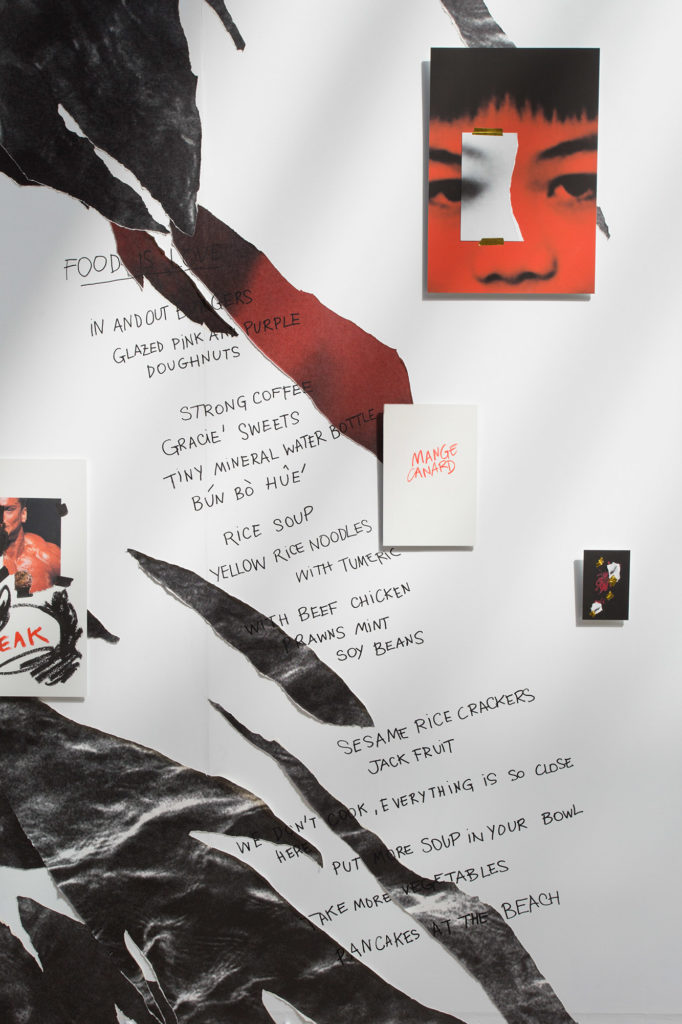

Long Distance Call has been displayed in several exhibitions in France and Europe, each exists as a separate installation work. How do you decide on the ever-changing ways that your work is presented?

I rarely exhibit my original collages. When I find myself in an exhibition space, I try to imagine how the work could inhabit the space. I also reflect on the work at a specific point in time. I once met with a neurobiologist who spoke about the concept of false memories. In reality, memories constantly recombine and change over time, even drift toward fiction. I incorporate this aspect into my installations. I don’t want to tell the story in a similar manner from one year to the next, because the way I remember and consider it also differs as time goes by.

A recent installation of Long Distance Call, which took place at Circulation(s) European Young Photography Festival from April to June 2019 in Paris, revolved around the concept of “crossing”. I displayed the collages alongside a silent video with no image, showing only subtitles narrating my uncle’s sea crossing in his own words. The background is a collage using fragments of an image of the sea and a still photo from a documentary about the Vietnam War. The blank space revealed underneath these ripped images evoke an interrupted journey. Gaps and emptiness are crucial to my research, which deals with silence. I want to explore how to give shape to absence.

Your work seeks to document and reconstruct the invisible side of history: missing identity, hidden memories, lost heritage. How could images draw these things into the realm of visibility?

Perhaps by not using photography as it is. The gesture of altering photos – splitting, recolorizing, extracting a blurred or abstract detail, anonymizing the subjects, then superimposing, piecing together fragments of images – is about playing with notions of identity and identification, removing images from their original context to project my own story. The tape patching these fragments resembles a kind of bandage that can be removed and reapplied, something as temporary and fragile as memory. I also draw figures to represent what is missing, or emotions that can’t be expressed through photos. The association of all these elements allows me to restore parts of my personal history.

You took a first trip to Vietnam in 2019, then came back for the Villa Saigon residency program shortly before the pandemic broke out. At the end of this journey, how do you feel about your relationship with the country?

During my first three months in Vietnam, I only began to learn about a Vietnamese culture that was connected in the slightest way to what I had known in France or America. I came to Vietnam believing that I was about to conclude my research, and yet the trip opened up so many unexpected paths. Coming back to HCMC early March 2020, I only had one week and a half of “freedom” before spending the rest of the residency to stay at home and create works using photos taken from the first trip. Then I had to leave Vietnam sooner than intended, on very short notice. It was another frustration, to think that: I’m here, finally, but once again something beyond my control prevented me from getting to know Vietnam better. At the same time, this period has enabled me to gain a more serene perspective. I’ve learnt to accept the frustration and disappointment about impossible things as an inherent part of my creative process. Similarly, I’ve come to compromising with not knowing the details of my own history, because I realized that the gaps in narrative are necessary for the construction and invention of each individual.

At this moment, what images do you have in mind of Vietnam?

While it remains a fragment of an image that I long to explore further, it’s nevertheless a reassuring one. I remember a lot of food because, during the social distancing period, I mainly experienced Vietnam through home-delivered meals. Then there’s the view that I had from my apartment at the residency. I spent hours on the balcony watching life go by outside without being able to participate. It’s a floating image, seen from afar, that I cannot reach.

Prune Phi (1991) is an artist and a photographer. After pursuing a Master in Artistic Creation, theory and Mediation, as well as a one-year residency at the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design in England, she graduated from l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie d’Arles in 2018. Prune Phi creates installations made from photographs, drawings, collages, collected documents, texts and videos. She depicts and questions the mechanisms of transmission within families and communities. Her work has been exhibited at the Centre Méditerranéen de l’Image, at the SiFest Off in Italie and during the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d’Arles.