President Hotel is a photobook documenting the last years of the once famous hotel of the same name, which later became an apartment building located at 727 Tran Hung Dao, District 5, HCMC. This nearly 60-year-old building, deteriorated and progressively abandoned since 2000, had vanished from the map when the photobook by French photojournalist Laurent Weyl was published at the end of 2016. The book consists of 80 color photographs and an essay by journalist Sabrina Rouillé, who accompanied Laurent in his visits of the historical building’s residents on the threshold of its demolition.

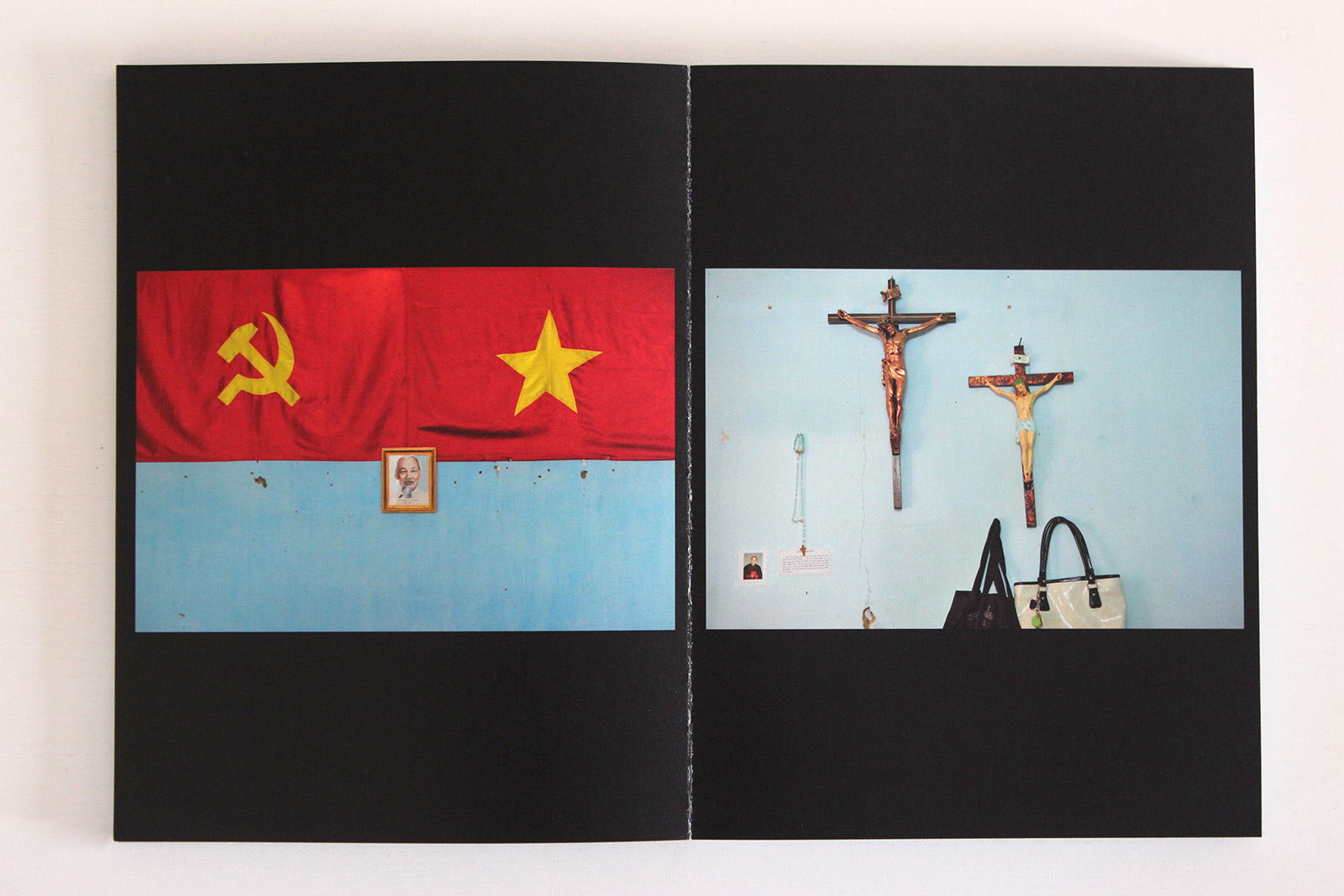

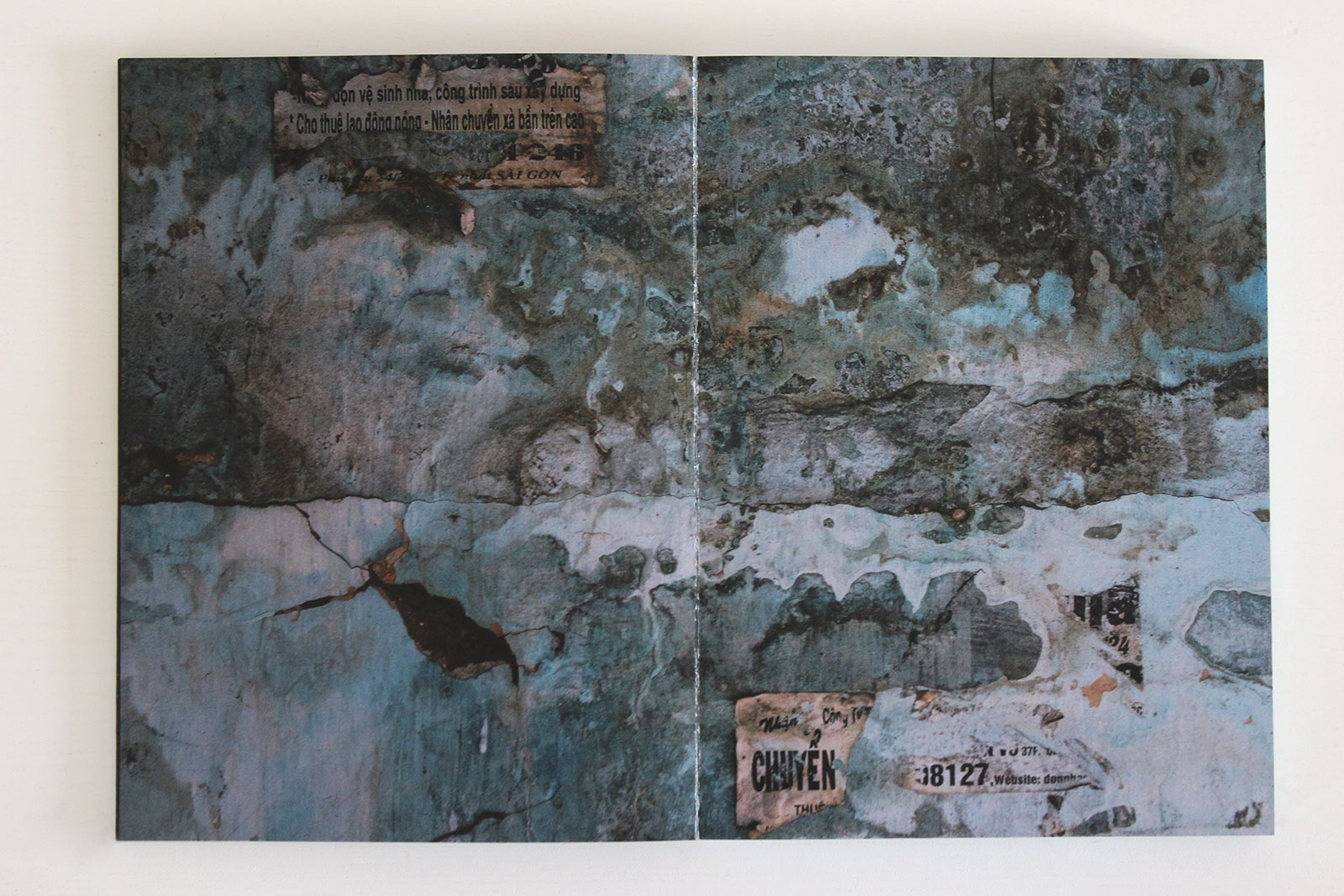

Slowly flipping through the pages of this solid, near square 200-page book, the audience solemnly enters the physical space of the building, and at the same time get immersed in a space of memory of a bygone era. The collection records scenes of daily life in the building, details of its architecture and still life of abandoned objects, thus offering an almost exhaustive study of the building and the life of its residents.

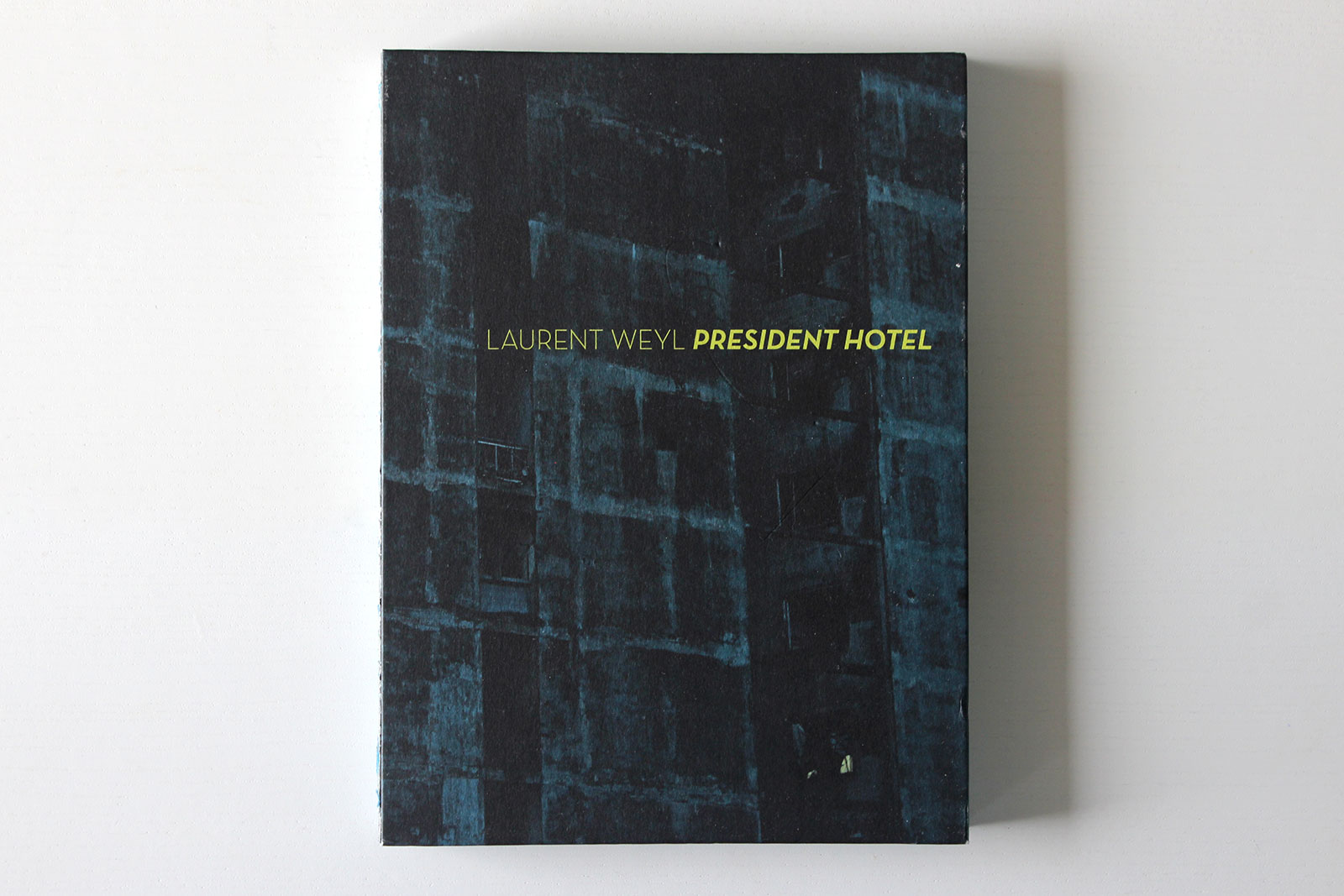

In addition to the images, every element in the book’s design intends to restore the building’s presence. If the cover is of its imposing facade, the book’s spine, left uncovered to expose the binding stitches, brings a contrasting fragility, as if to remind the audience to gently approach the remaining traces of a now vanished monumental structure. The two background colors – deep black and plaster blue – evoke dark, narrow hallways as well as the signature paint colors of the building.

From his office in Paris, Laurent Weyl recalls how the book President Hotel came to be, his attachment to Vietnam, and the central role that time plays in his photography practice.

You first came to Vietnam in 1992, went back several times afterwards and lived in Saigon from 2011 to 2016. What is your relationship with the country?

The first major experience always leaves a deep mark on a person’s life. Vietnam was my first time traveling alone and doing a reportage as a photography student. Two friends of mine and I received a grant to travel to Vietnam for one month. I made all my professional mistakes there – I worked on an awful lot of topics only to end up with no story to tell, while I should have focused on just one topic. Vietnam was truly the place where I learned my profession.

How did you become a photojournalist?

At the start of my career, I worked as a photo assistant in order to make a living with photography. For 10 years, I assisted photographers of the Magnum and VU’ agencies, and also fashion photographers. Then I worked for three years in an advertising agency. It took me a pretty long time to find my way back to what I genuinely wanted to do, which is photojournalism.

I follow long-term projects and rarely cover spot news. I work on subject matters which require considerable time – from six months to three years of preparation, then one month in the field, not only to photograph but also to investigate. Usually, what I have gathered from my desk research in Paris is quite different from reality. Sometimes I worked on an angle and completely changed it while investigating on the spot. Time allows me to adapt and adjust my work.

What is your process with President Hotel?

In 2001, I started a personal project on rural migrants in HCM city. Then I concentrated my work on the KT4 migrants (who have temporary registration for a period of less than six months) to provide illustration for a report conducted by the NGO Ville en transition (Transitioning town). While inquiring about the housing conditions of university students from rural areas, I heard about President Hotel. On its top floor, there were cheap rooms for student rent. In 2011, I decided to move to Saigon, because the topic demanded the photographer to live locally – you would hardly get accepted by the residents within a short amount of time.

I was lucky to have a Vietnamese friend who was willing to interpret free of charge. In the beginning, the residents were cautious, but as time went by, the security guard was sympathetic towards us. After we returned several times and offered people photo prints, they finally opened their doors and welcomed us. Spontaneously they would invited us for dinner, and confide their stories about the building. These visits spread over two years.

The building emerges from your photos as a character with a form and a personality, suggesting an intimate interaction between the physical space and the photographer. What are some of your memorable experiences inside the building?

I basically walked a lot. I wandered along the corridors, went up and down the stairs, and waited. Sometimes I got lost and could not identify what floor or which side of the building I was on. When you look out the windows, you would see a ceiling instead of the sky. You don’t know if you are at the top or on the ground, and you’re completely disorientated. It’s important to familiarize yourself with the place and spend time there. Taking the time also allowed me to change my viewpoints. For instance, I lingered at the barber shop for half an hour and took a lot of frontal photos, until I stepped behind the wall and came to produce this image, which is more suggestive than demonstrative.

There is a cinematic aspect in the way the photos privilege oblique light and play with the contrast of light and dark. Was this your intention?

Yes and no. This was a gigantic building with 13 floors and eight blocks, connected by corridors of 100 meters in length and over three meters in width. The windows along the corridors allowed natural light to enter from both sides like in a studio or on a film set. To me, lighting is crucial. In the same spot at different hours of the day, light revealed things that had remained unnoticed to me. I took the time and waited for something to occur. Like the photo of the coffee shop, I went back there several times and happened to arrive just when the sun shone precisely as it should.

Can you tell us about the design of the book and the place of the two texts?

The book seeks to convey the spirit of the building, which was constructed in brutalist style. From the cover, we recognize its dark facade – the absence of windows from the outside only highlights its sad and gloomy look. We can feel the decaying plaster of a building that hadn’t been maintained in several years because people knew it would be demolished. In the limited edition, the book was hand-sewn in Coptic fashion, with column patterns representing the blocks and the blue stitches, the corridors.

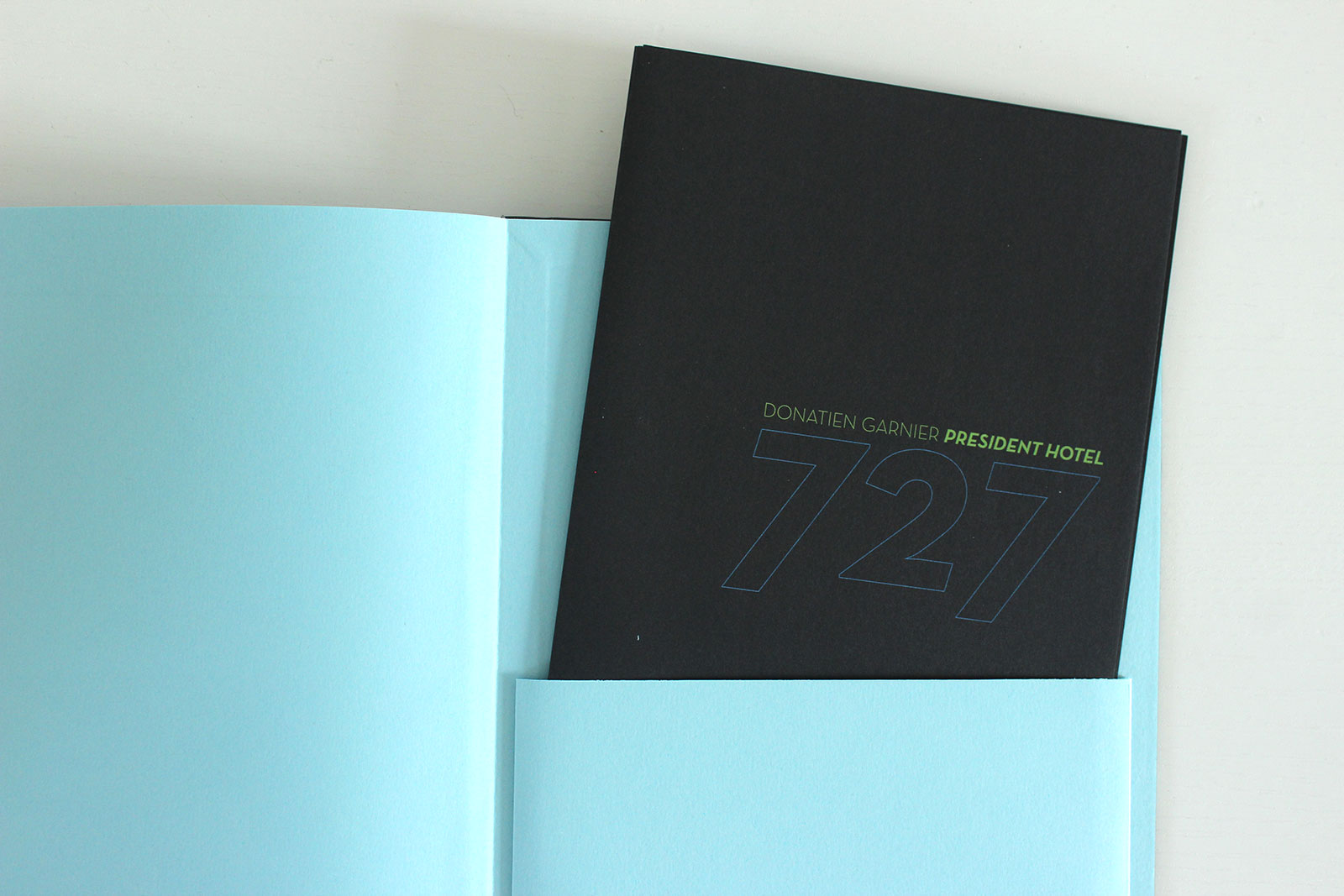

Each of the two texts reveals a facet of President Hotel. The documentary text of Sabrina Rouillé retraces Vietnamese history through the building and the journeys of its residents. A poem/typographic design work by Donatien Garnier, created during his residency in the building, is printed on a separate poster, folded and inserted on the inside of the back cover. It seeks to translate his perception of the place and capture the building as a human being.

Some photos from President Hotel also appear in your photobook titled Ghosts of Saigon. Can you share more about this work in progress?

The point of departure of this project is my reflection on what ghost is. Ghosts are very present in Vietnamese folklore, in the stories that haunted President Hotel, in the spiritual life of Vietnamese people, but also there are also ghosts of the past, the war and the colonial era. So I went to pagodas, villas and zoos that were built by the French. These locations serve as a trigger for the search of my own ghosts regarding the country. When I first came to Vietnam in the early 1990s, I felt affection for so many things that no longer exist, such as the images of bare chested workers in small mechanical factories, whom today I can only find on the far outskirts of HCMC. I had the opportunity to witness the country’s development, and would like to leave a testimony of the things I once felt before they disappear completely.

With this project, I want to step outside the photojournalist approach and make a plastic work about the notion of ghost. It will take the form of a “book-object” using a very fine type of paper with translucent text.

As a photojournalist, how do you reconcile your personal projects with commissioned works?

Nowadays, as a photographer, you have to do everything: seek funding, take care of post-production and sell your works, among other things. Striking a balance between my own photojournalism and commercial photography is always a dilemma, because it takes a lot of time to seek out networks and follow itineraries that are very different. Unfortunately, commissioned photography doesn’t occupy much of my time, while it is increasingly difficult to live off press photo.

While I work independently, I’m also a member of Collective Argos which brings together editors and photojournalists focusing on documentary journalism. This allows us to share our desires, our problems or our reflections, and most importantly, to carry out projects together. Every three years, we work on a collective project that investigates a social issue through 10 different stories, most recently on energy transition. It’s by working together as a group that we are able to obtain funding from institutions, organize exhibitions and publish books.

Laurent Weyl is a documentary photographer focusing on social, environmental and geopolitical issues. He has pursued long-term projects investigating urban poverty, climate refugees as well as socio-ethnological topics. His work can be seen in several photography festivals (Visa pour l’image, Arles, Vannes) and in the French and international press (Figaro Magazine, Geo France, Geo Allemagne, Flair Italie, Alternatives Internationales, El Pais, Times). In 2014, he received the Vienna International Photo Award and the SCAM-Roger Pic Award for his series President Hotel.