“Whereas abundant journalistic snapshots tend to collect spectacles of ghastly pain and fortify demarcations between utterly simplified factions, Võ’s most haunting pictures unveil encounters, precarious and transient. These fleeting situations, reincarnated as calm flat photographic surfaces, live on not as hollow representation, but as animate presence, where the struggle, seen anew, becomes distinctly other. The imaged wartime of Võ An Khánh carries a self-replenishing, near-mythological energy that deforms or transforms the prefixed meanings of ideology, outlives the noise of dogma, outlasts the propaganda of discourse.”

—Nguyen Hoang Quyen, co-curator, Sàn Art

In early June 2020, the contemporary art space San Art opened the exhibition titled Masked Force, presenting Vo An Khanh’s photographs of the revolutionary forces in the Mekong delta taken from 1961 to 1974. This is the first solo exhibition of the veteran photographer’s work at San Art since the group exhibition a decade ago. Despite taking place in a different context, the show retains the similar spirit of preserving and transforming wartime memories so as to engage in new dialogues.

The photographer has authorized the curatorial team to access and select images from the vast archive of his enduring career. 14 digital prints are arranged into groups about the rear activities of medics, performers, and print workers, and the secret meetings among the revolutionary cadres deep in the mangrove forests, whose shadow becomes the backdrop for a quietly sacred stage.

The exhibition begins with the scenes of American helicopters dropping troops and of mangroves decimated by chemicals. The only pair of images depicting the brutality of the frontline heighten the heroic atmosphere in subsequent photographs of performance rehearsals from the rear. This series of group portraits praise the revolutionaries’ beauty and strength, freezing them in heroic poses.

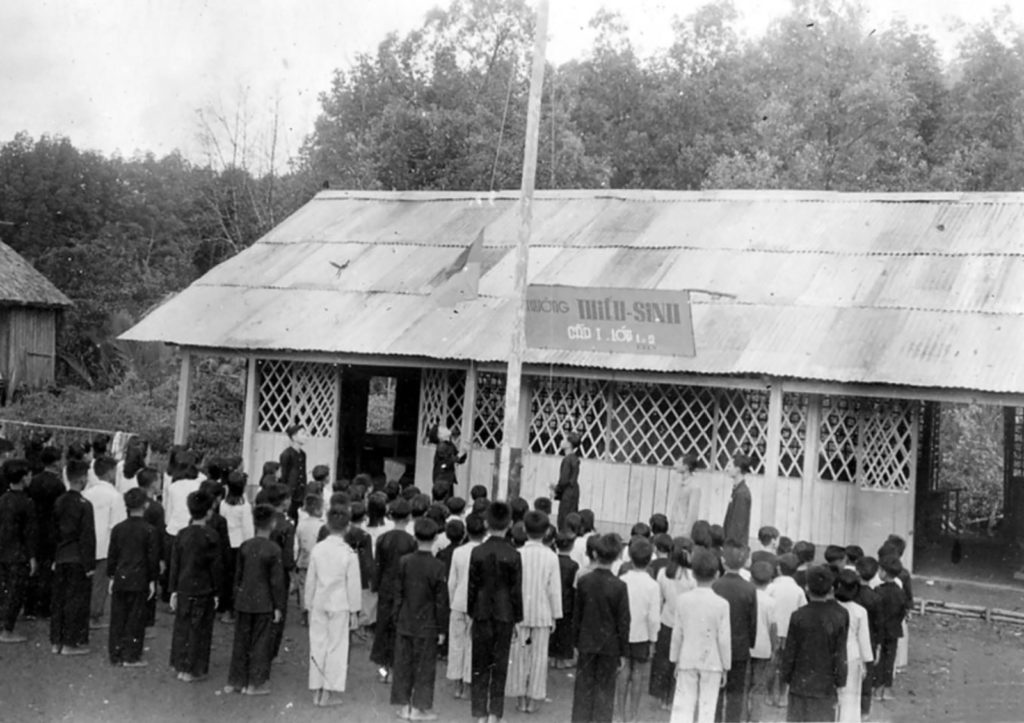

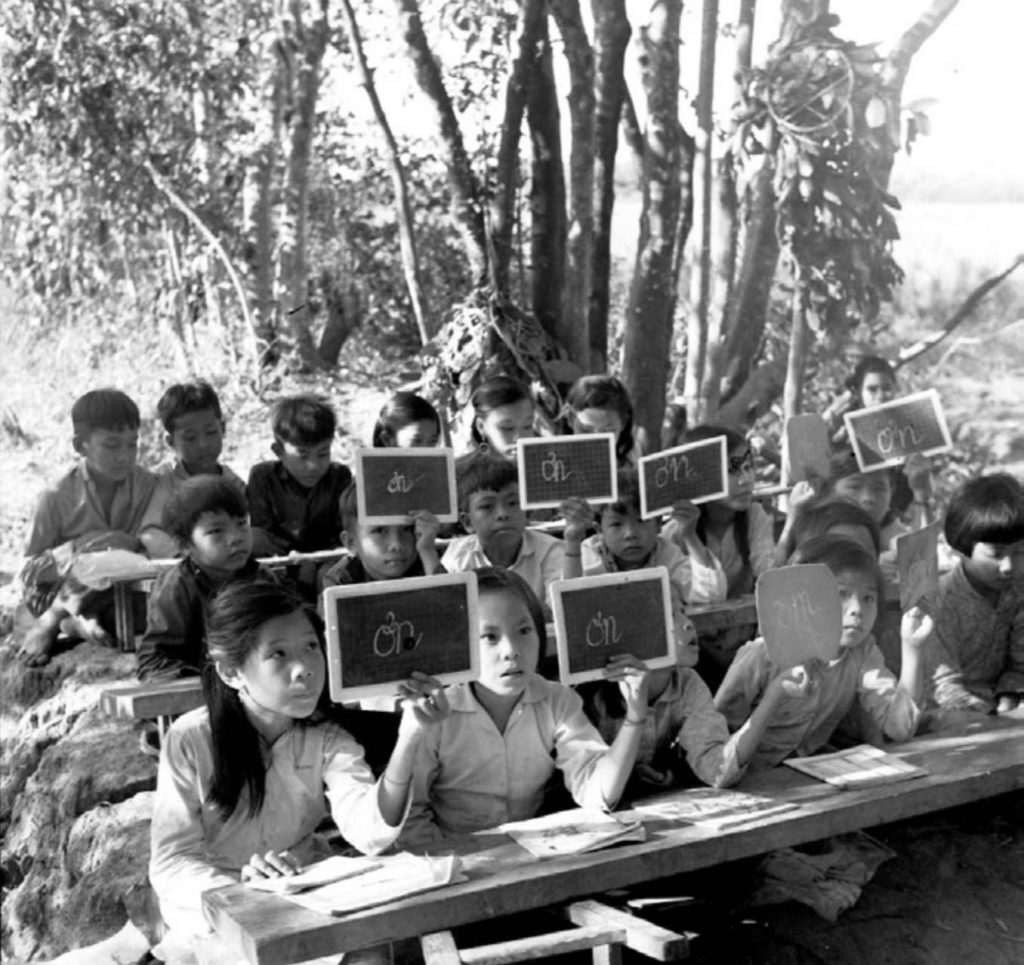

An unsettling energy grows gradually and throughout the recurring imagery of anonymous subjects under their white hoods. The caption reveals that they are revolutionaries who had to wear masks to hide their identities among themselves in case of capture and interrogation. These concealed facial features and expressions stun and caution viewers. Woven into this heavily cautious air are some day-to-day outdoor portraits of children studying and playing, thus blurring the space-time within this sequence.

The exhibition also includes many iconic works from Vo An Khanh’s oeuvre, particularly Mobile military medical clinic during the period when the enemy is defoliating U Minh forest. When the image appeared on the front page of the New York Times, many critics attributed it with the adjective “surreal”. The surreality of Vo An Khanh’s photography does not come from eccentric scenarios dramatized for shock effects. Different from images artfully staged that leave no room for surprise factor, the power of documentary photography is beyond prediction, as critic Teju Cole wrote, “The photographic surreal, like the sublime or the obscene, is subjective. It cannot be locked down to a theory, codified and filed away under an ‘ism’. Rather, it arrives like a metaphysical gift, showing up when it is least expected to conquer logic and haunt the imagination.” The sense of urgency, of alert, of suspense, and the temporary mobile structures that disappear without traces are created right on the thin line between life and death, and therefore almost unrepeatable by narrative formulas in cinema works of the same subject.

The surreality of Vo An Khanh’s photography does not come from eccentric scenarios dramatized for shock effects. Different from images artfully staged that leave no room for surprise factor, the power of documentary photography is beyond prediction.

Born and raised in the Mekong Delta, Vo An Khanh possesses a keen instinct for mangrove forests – the sacred natural landscape that then became strategically significant in that uncertain period. He trudged through the fields, documenting the relationship between human and nature in his carefully composed frames. The forest nurtured, covered, and witnessed in silence the many ups and downs of its inhabitants. People live in and with the forest, a timeless landscape embodying the vestiges from the past, improvised by the present and suggestive about the future.

Vietnamesse photography is embedded in the layered history of warfare. Like many other propaganda officers during the revolution against the US, Vo An Khanh sees the act of photographing as a service for the Common Cause. After fulfilling such duty, his works challenge genres, subjects, and ideologies, and continue to live their own lives. In front of contemporary viewers, these documentary photographs reach beyond their role as mementos. They rely on neither symbols nor icons and are hence continually renewed.

Vo An Khanh was born in 1936, in the village of Ninh Quoi in Hong Dan District, Bac Lieu Province, south-western Vietnam. During the 1960s and early 1970s, he traveled with a guerrilla unit to document the front line of the Vietnamese resistance against the U.S. in the Ca Mau region. He also managed the Photography Department of the local revolutionary cause and documented events related to frontline music and dance events. Between the years 1962 and 1975, Vo An Khanh staged a photographic exhibition in the exceptionally challenging condition of mangrove forests. His two well-known photographs, ‘Mobile Military Medical Clinic’ and ‘Extra-curriculum Political Science Class,’ were included in this traveling show, which Vo An Khanh himself developed on the spot using natural light.