The Long Bien Bridge in images is a long-standing cultural symbol of Hanoi and in real life a neighborhood of slums where immigrant workers reside. Tasked to photograph Long Bien, the photographer is at the crossroads of either perpetuating the dazzling emblem of the “historical witness” or tackling with what constitutes the current reality of the place. Boris Zuliani decides to take a detour by making polaroid portraits of canoodling couples across Long Bien bridge without burdening himself to speak about anything profound.

“I don’t need to talk, polaroid is a language in itself”

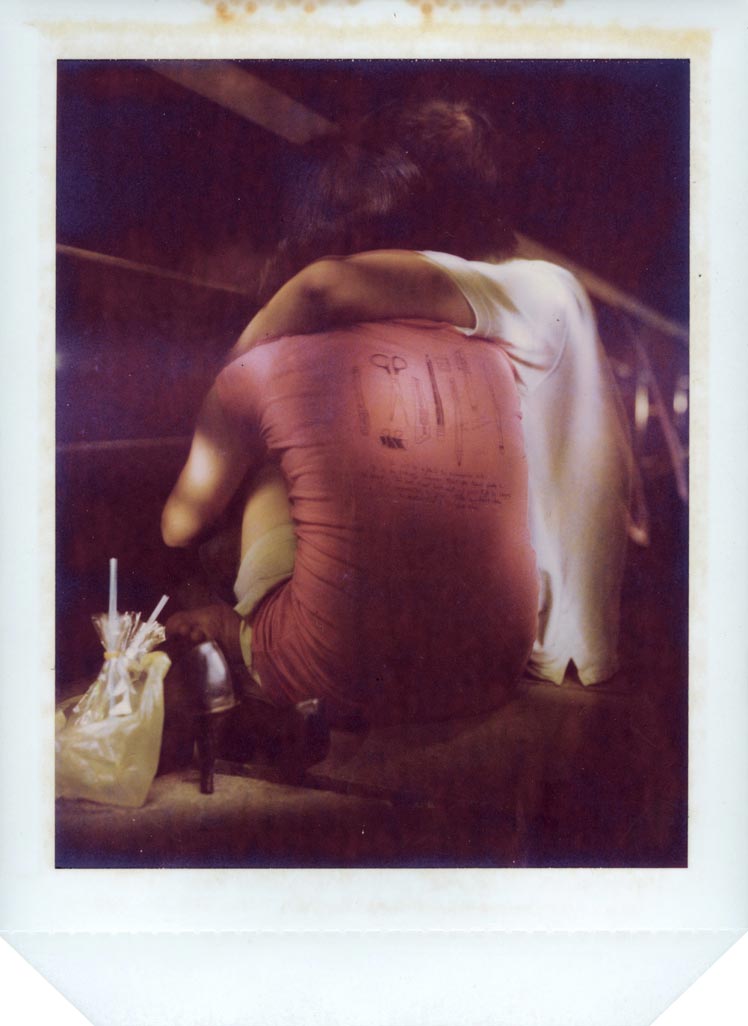

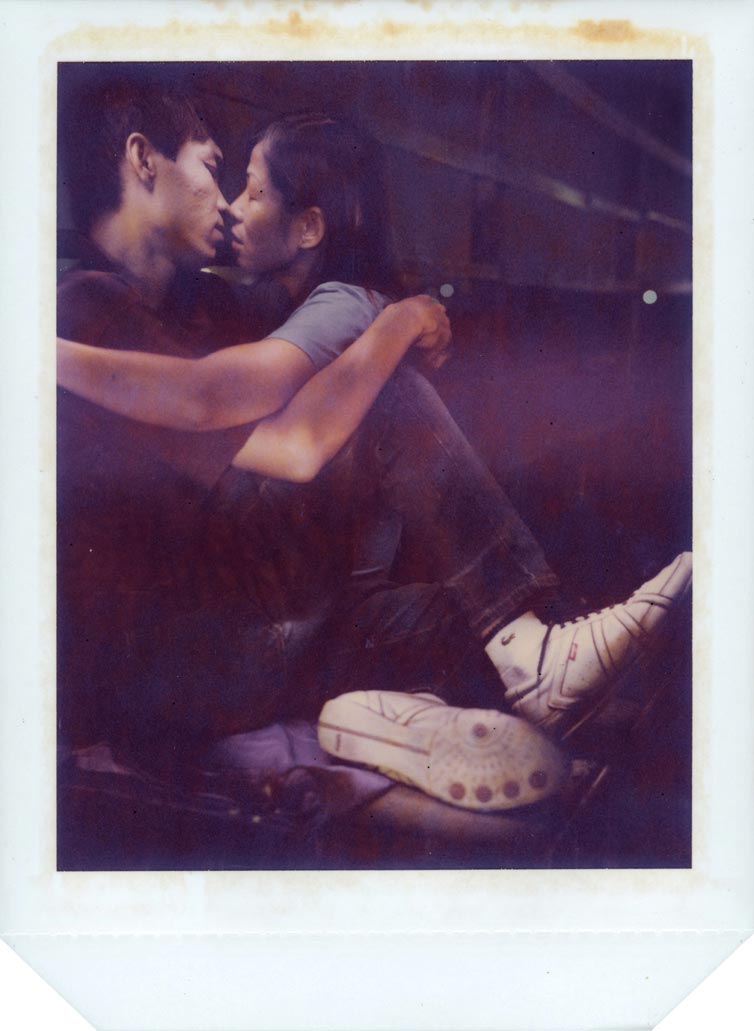

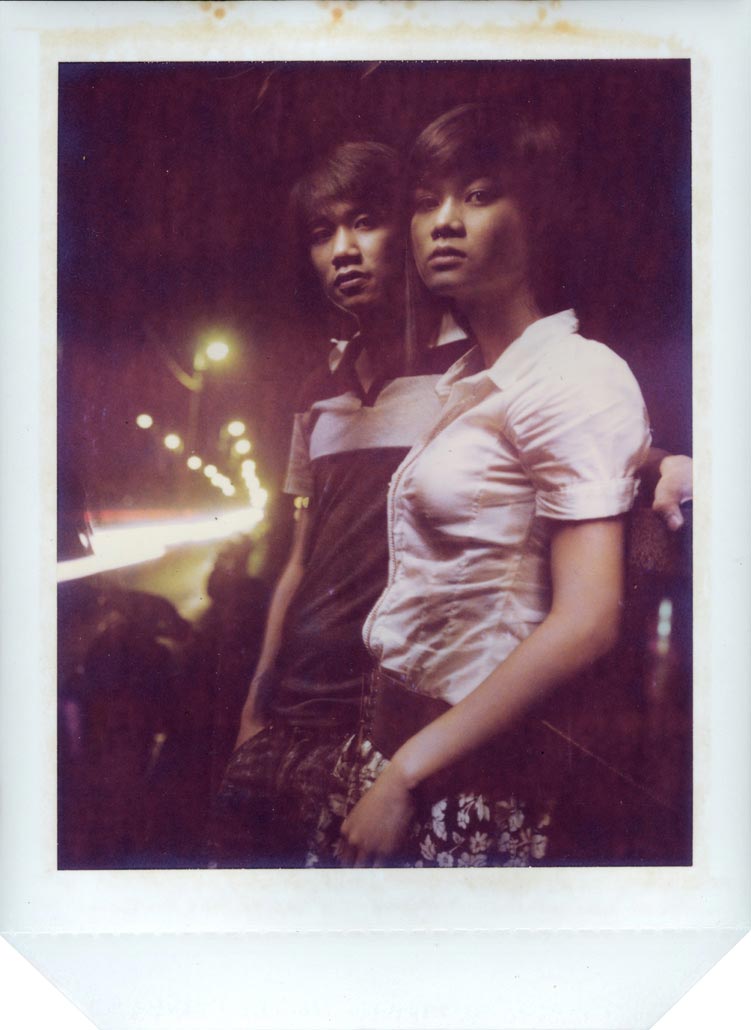

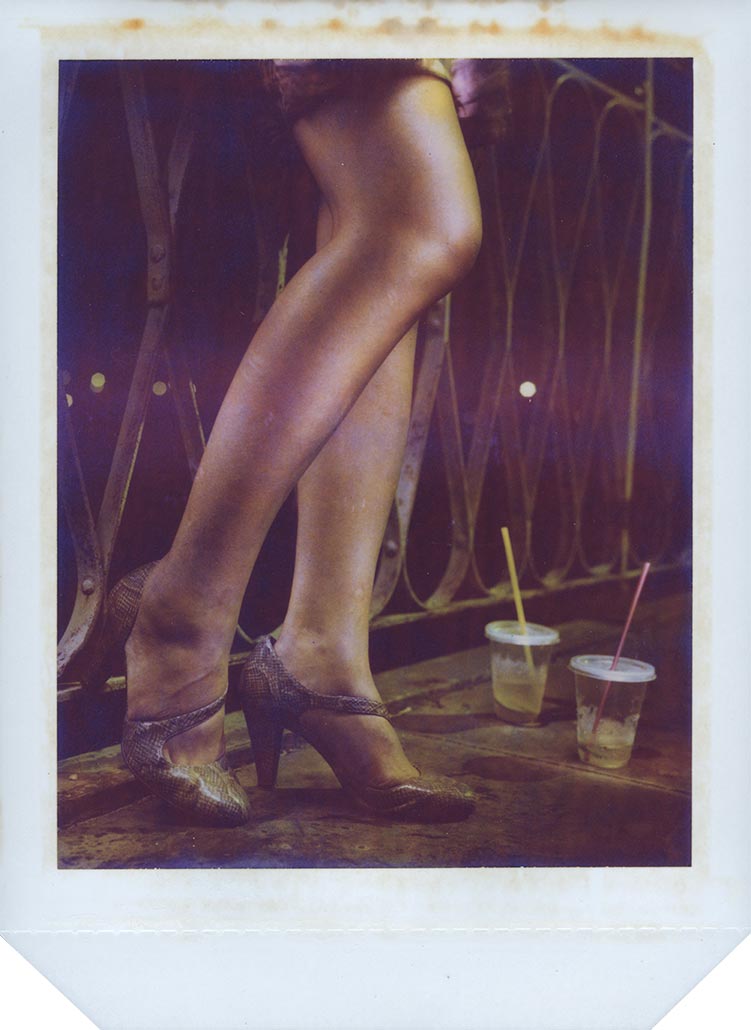

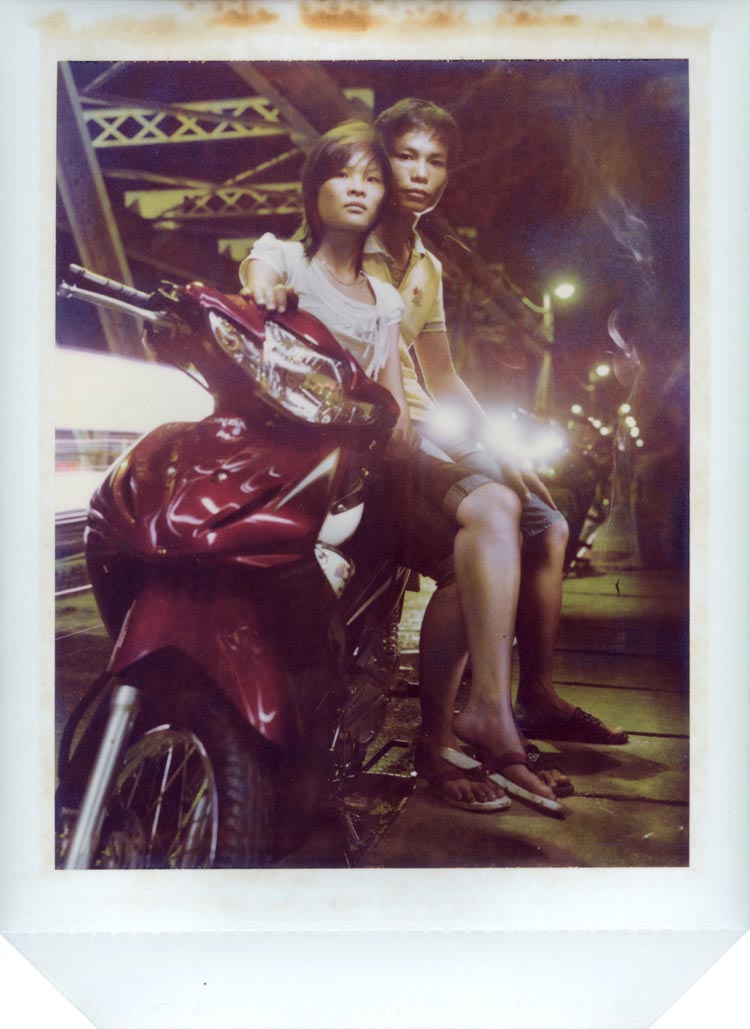

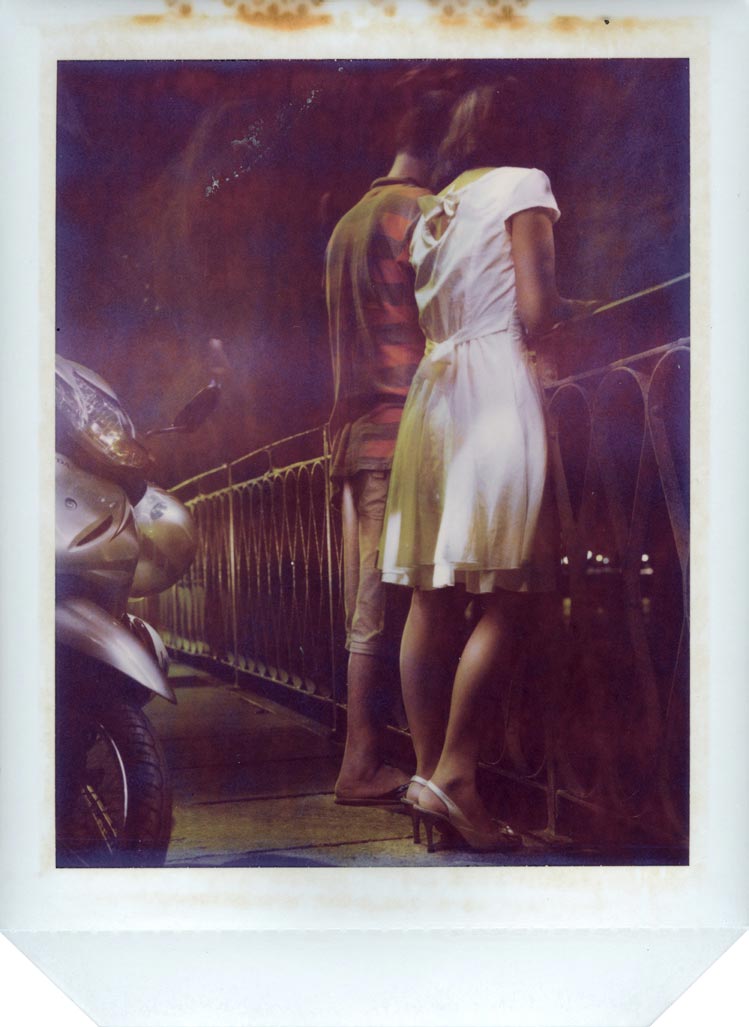

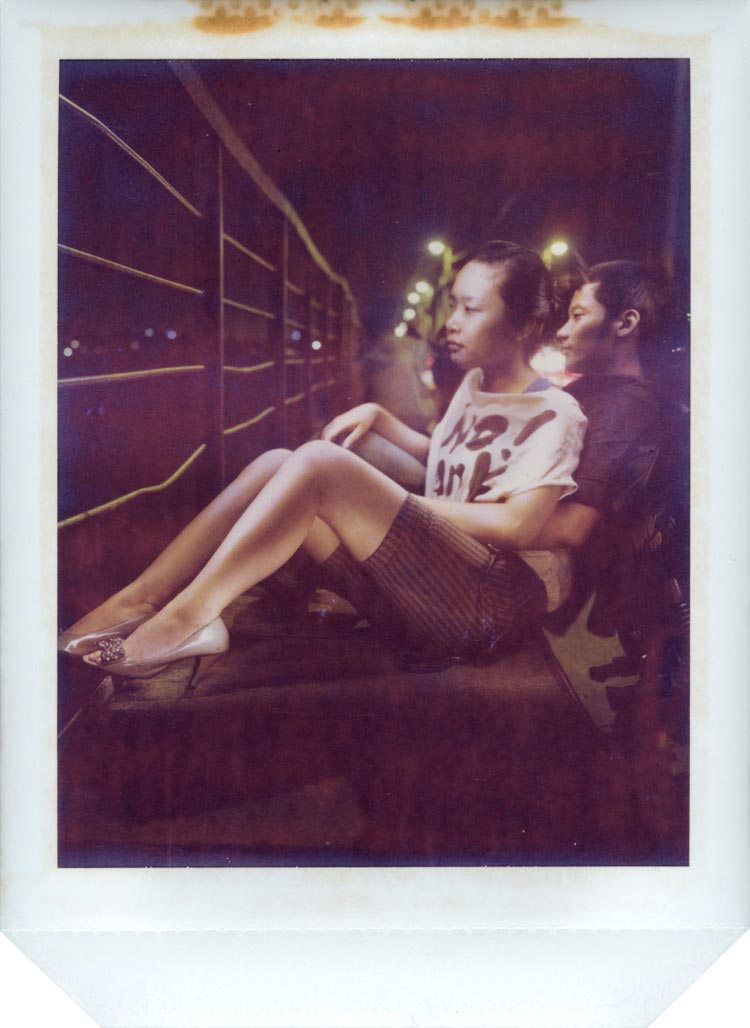

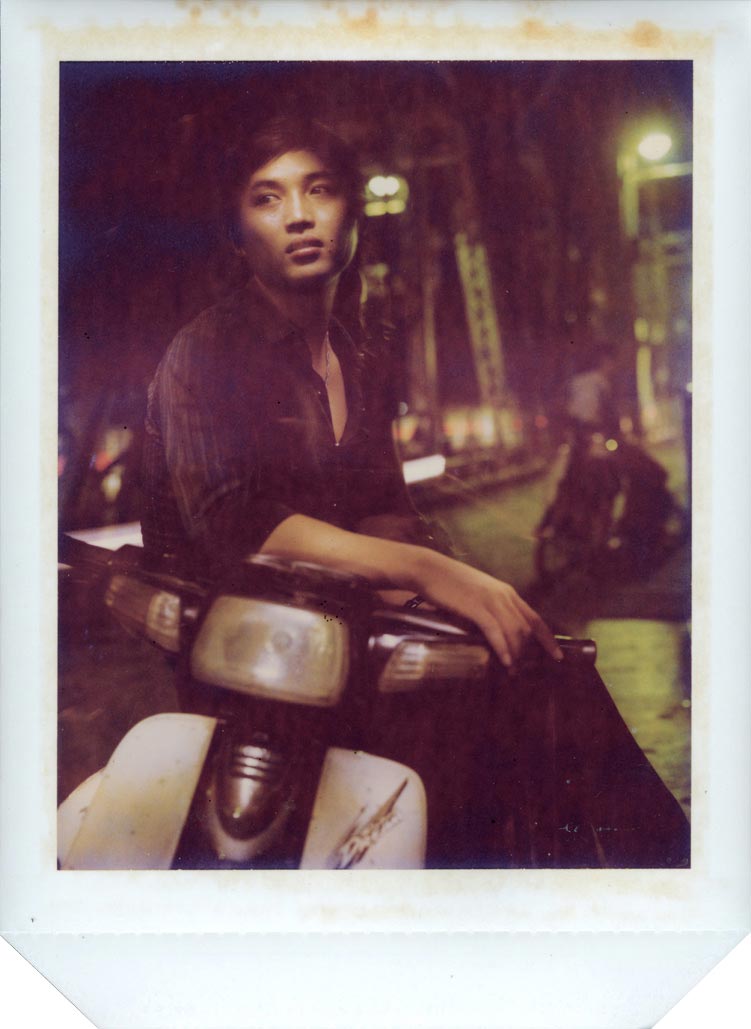

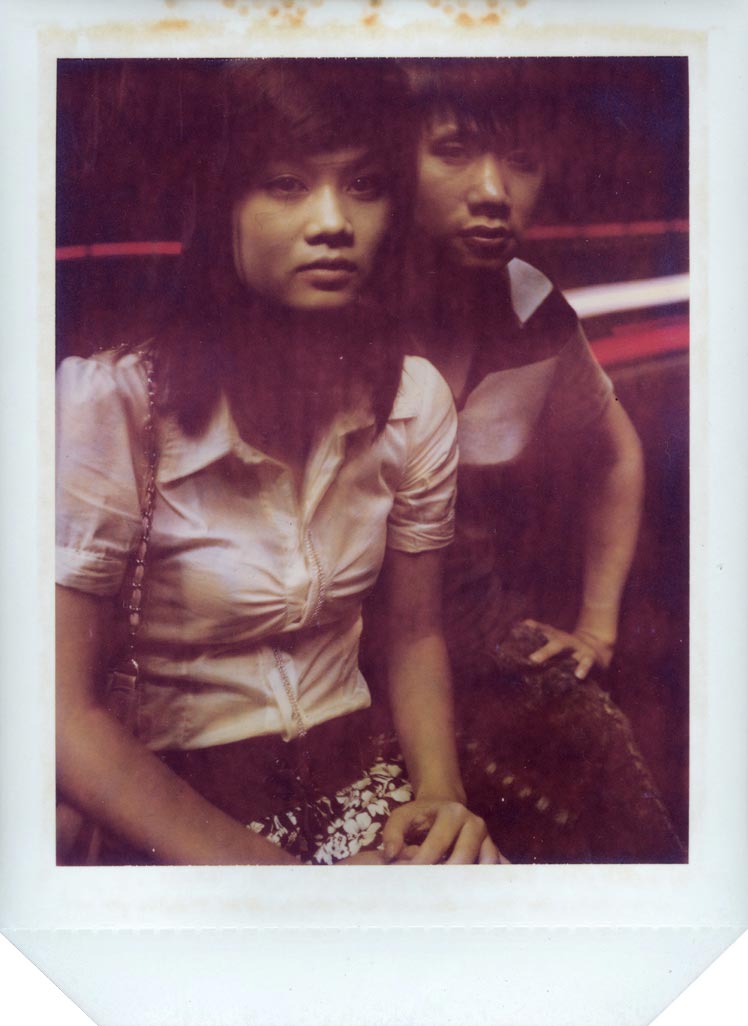

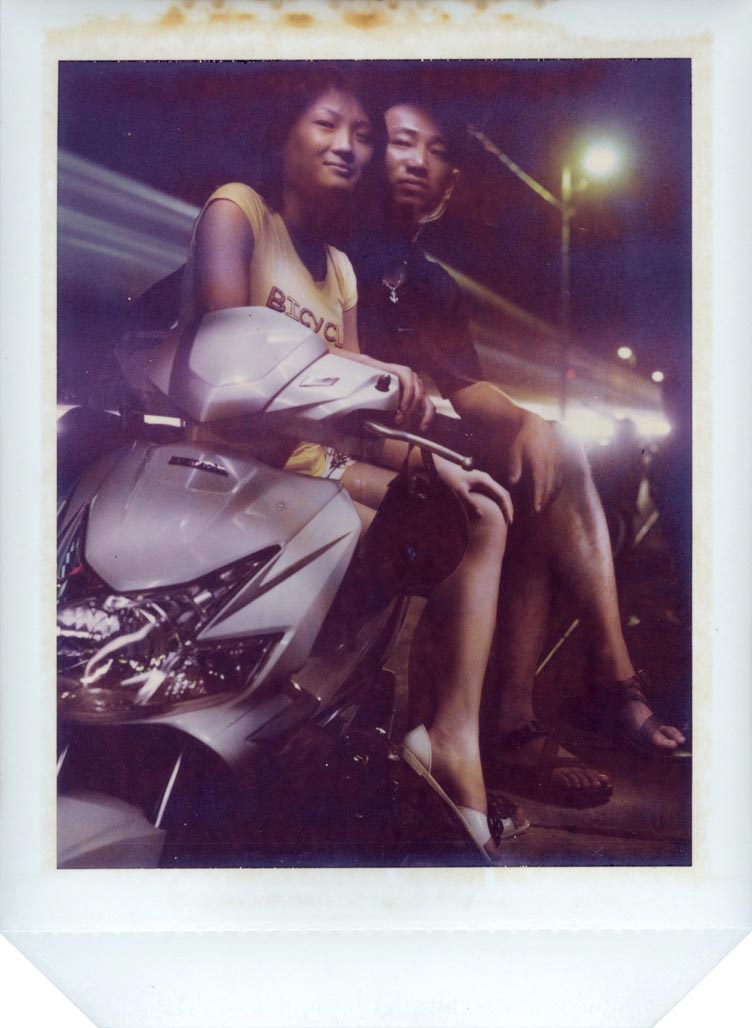

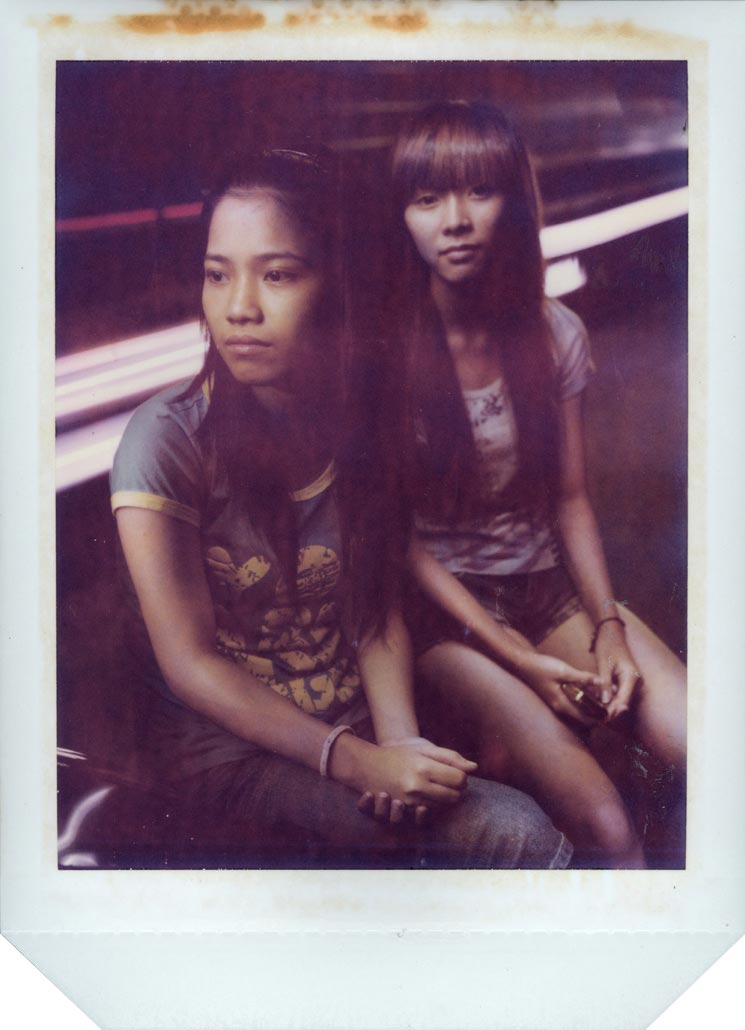

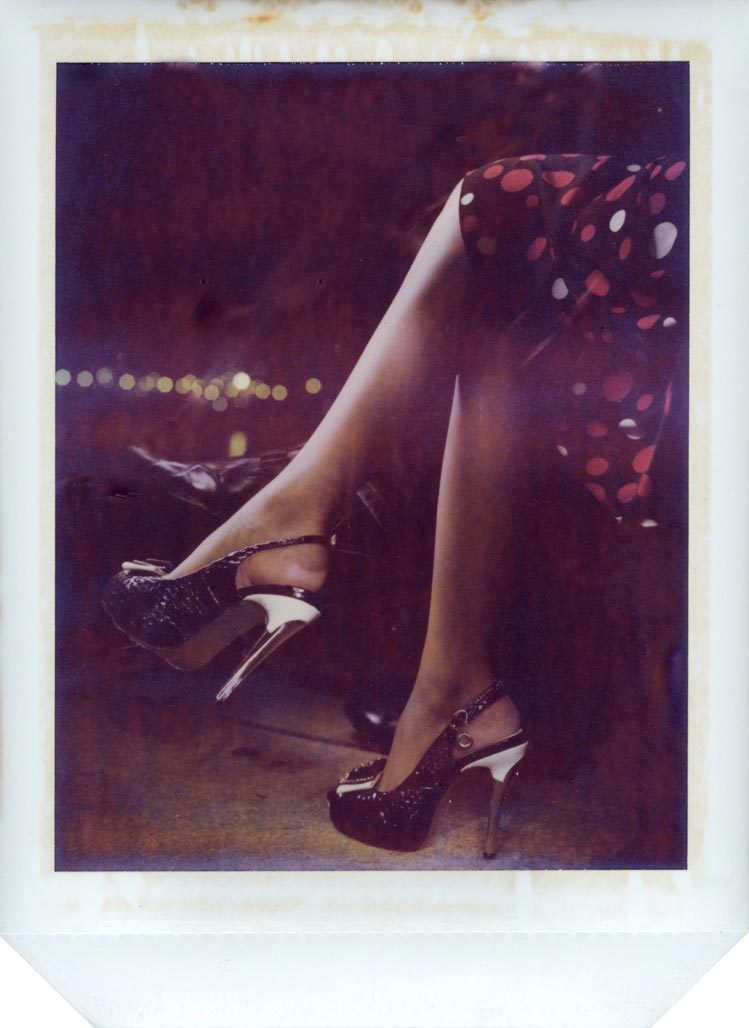

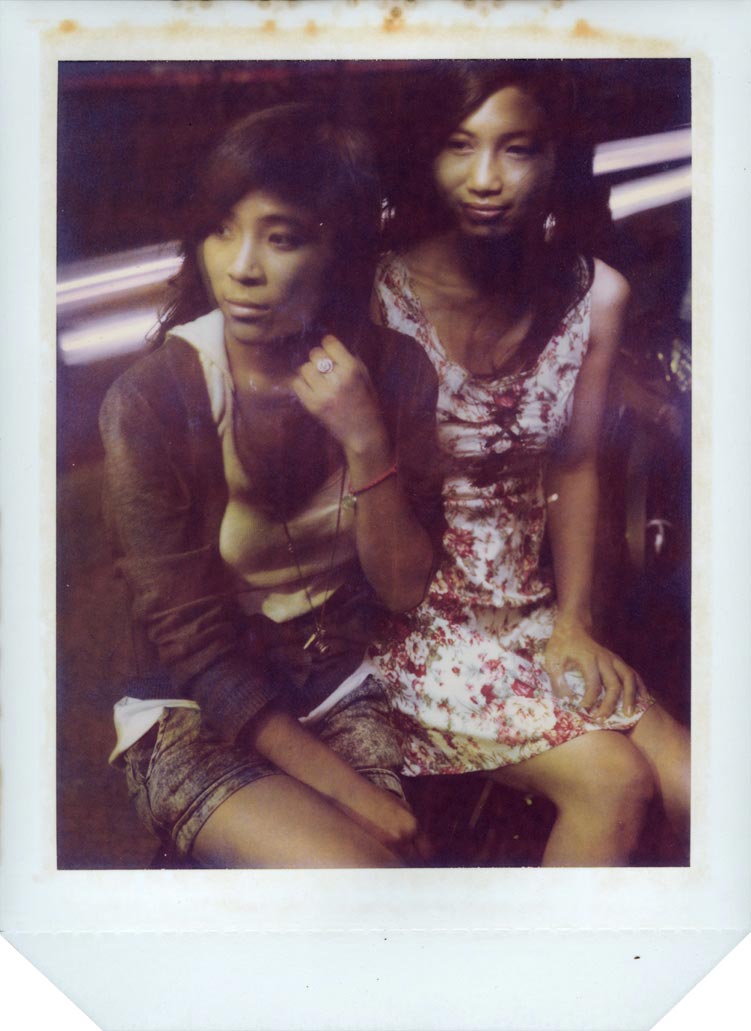

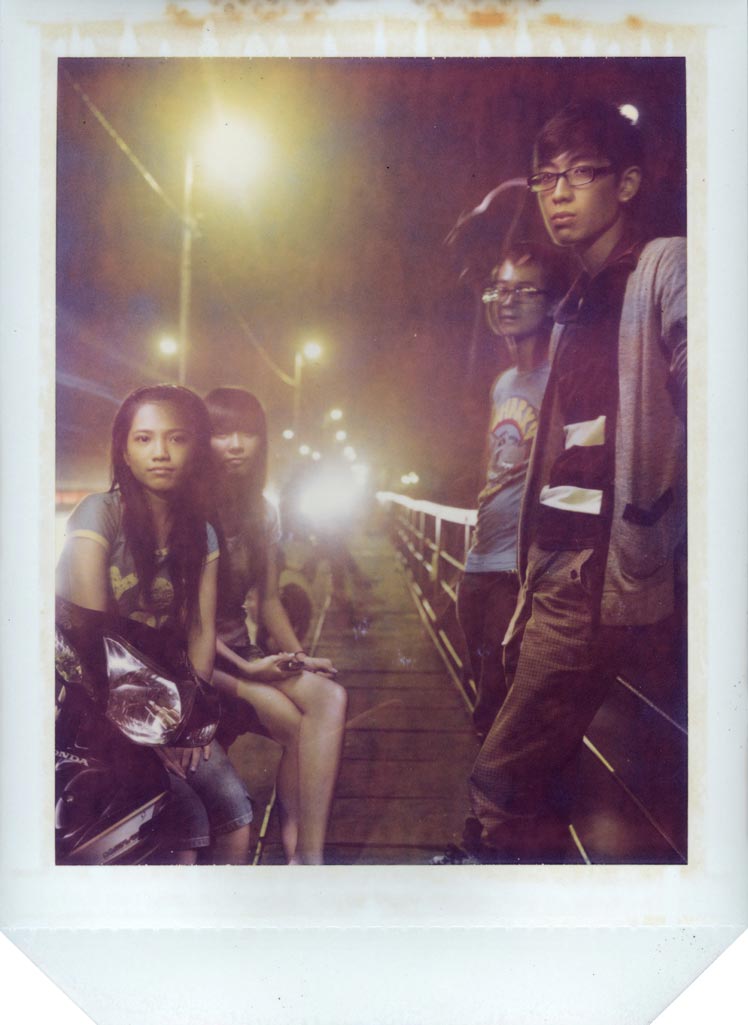

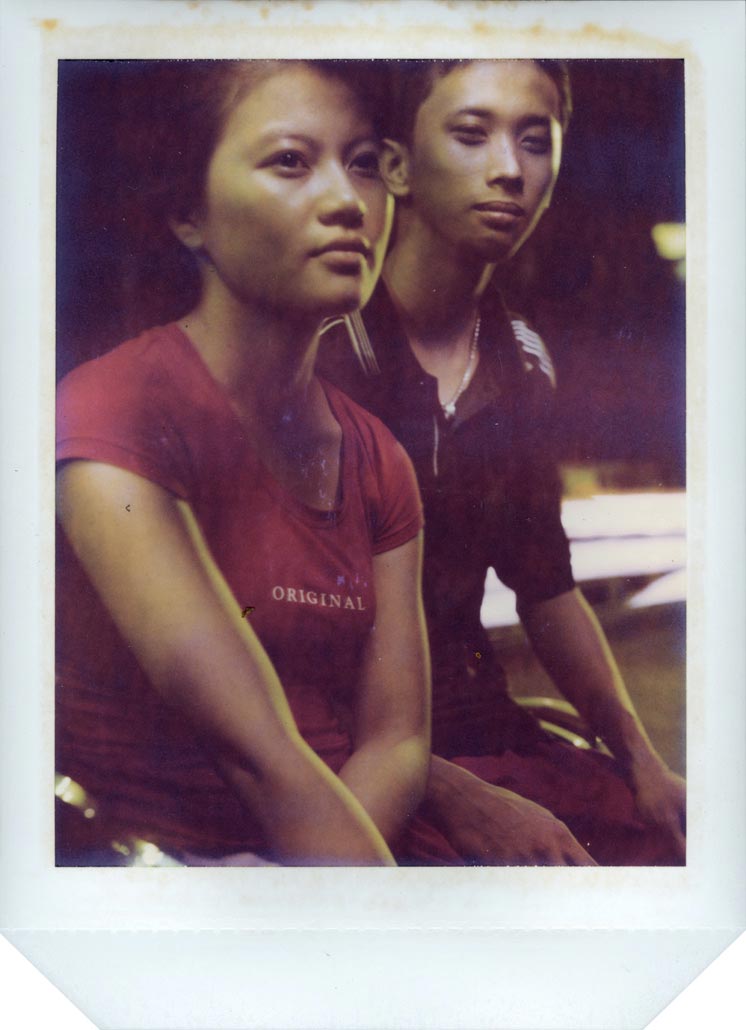

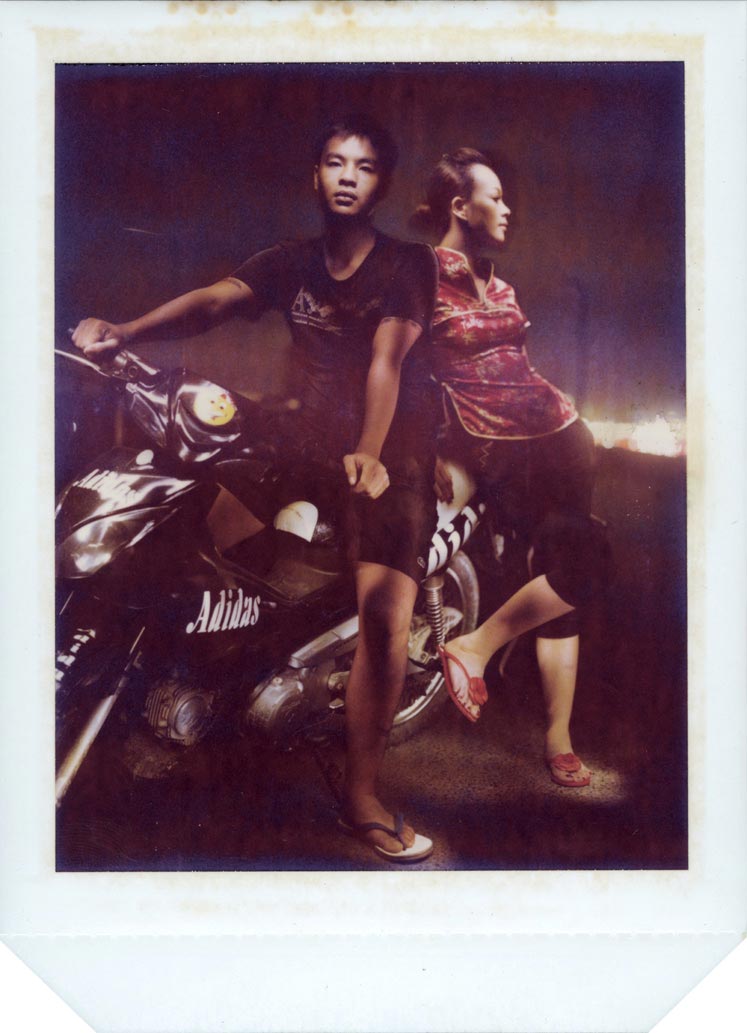

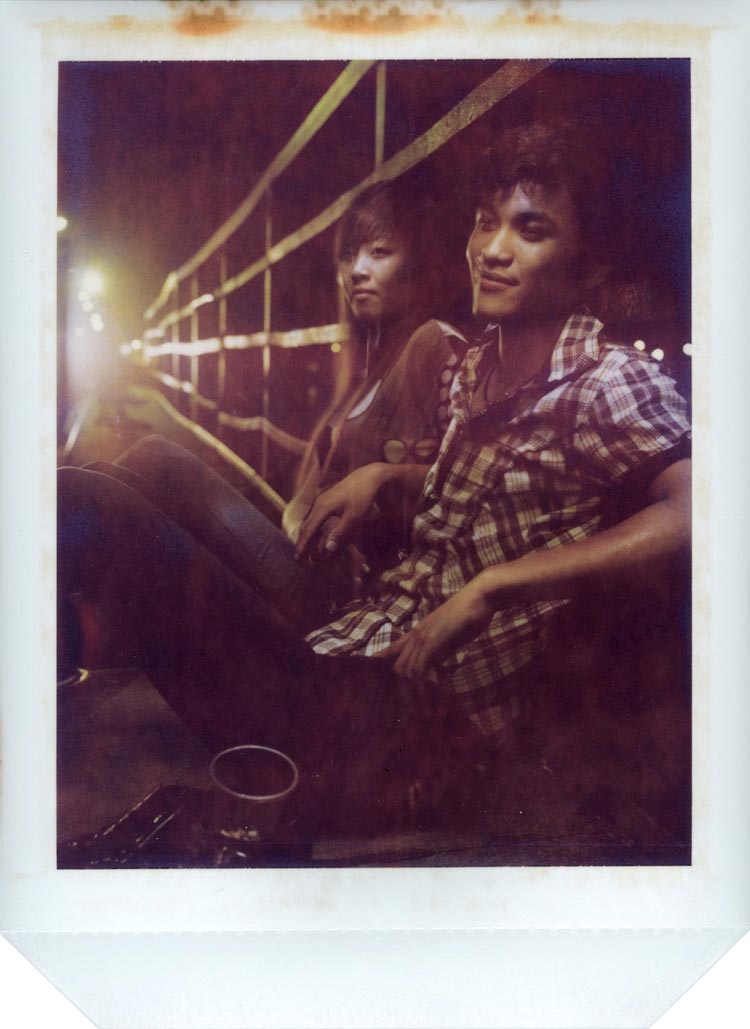

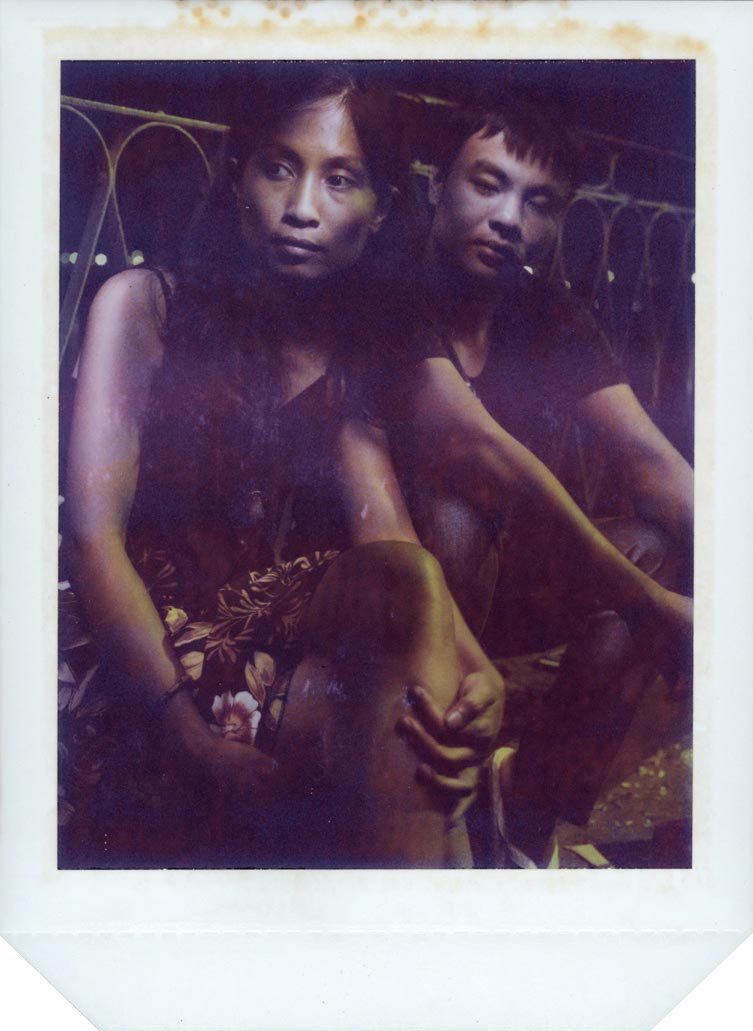

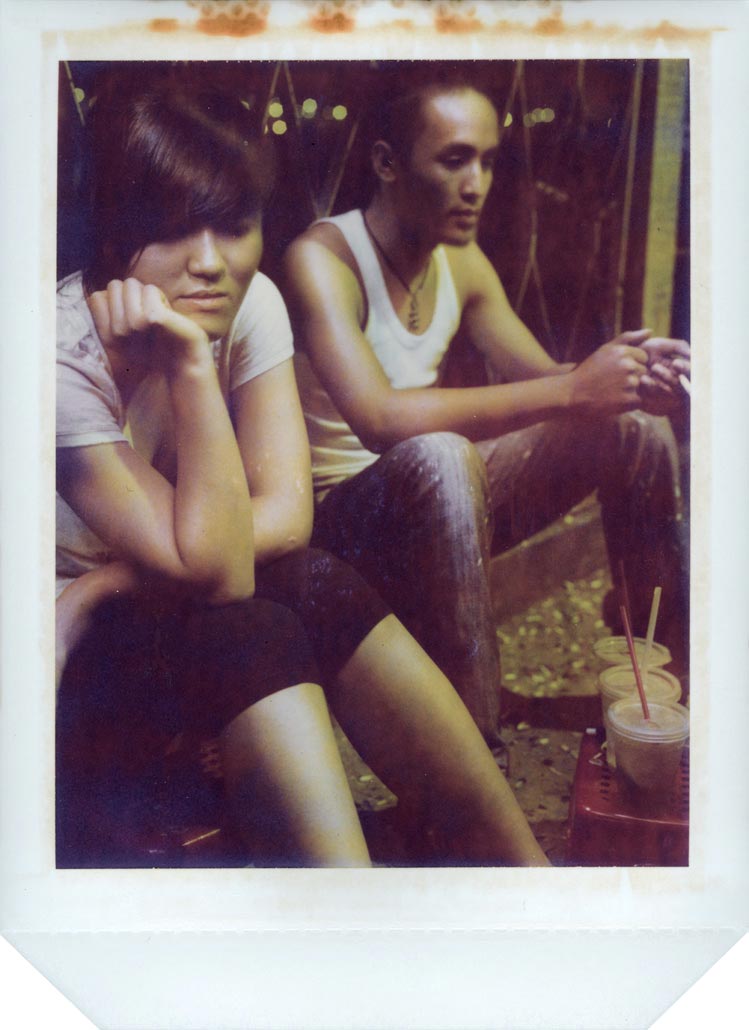

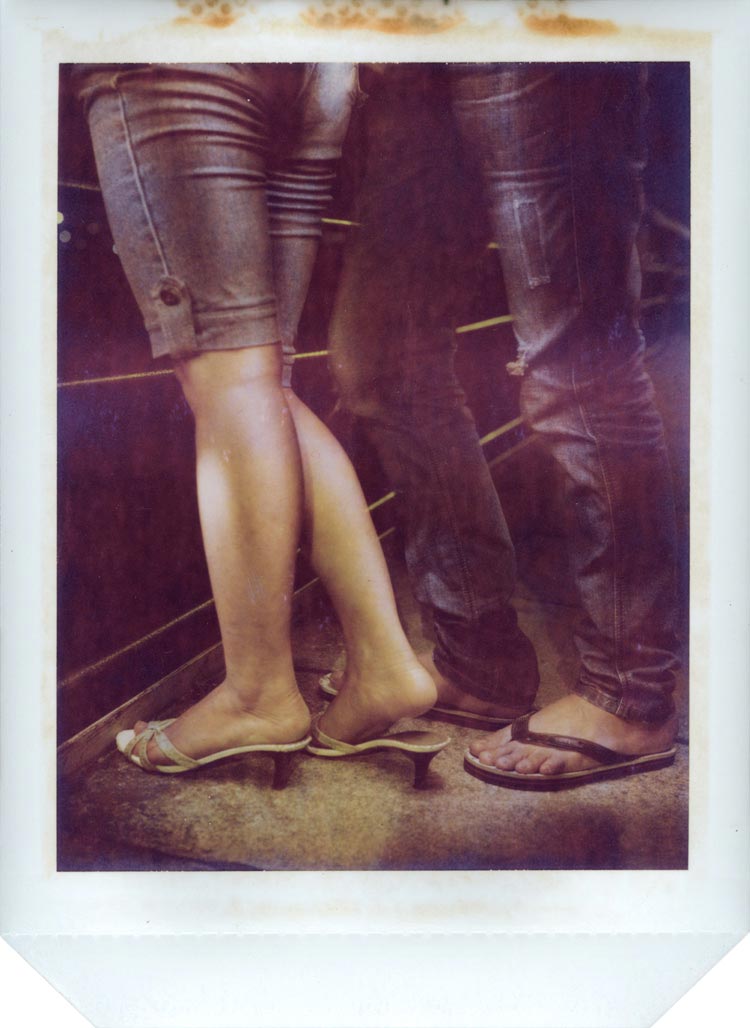

At first glance, his polaroids, scanned with the borders intact, look both aged-old and timeless. The soft hues of outdated films instantly bring about a sense of nostalgia while the bridge in the background has been weather-beaten for a century. Viewers can only obtain a sense of time by taking a closer look at the people portrayed: their hairstyles, their dresses, the footwear tailored for the date. But even so it is challenging to pinpoint the exact time when the photos are taken, as for long, young lovers have been drinking sugarcane juice from plastic cups and hanging out there where cool breezes from the Red River and relatively personal space on the motorbike invite romantic gestures. Turning their back on the ever-flowing streams of vehicles, they gather at the dilapidated bridge, one among few places in the capital that welcome public display of affection.

Boris was living in Hanoi when the Polaroid company announced the discontinuation of instant films in 2009. Investing all the money he could put aside at that time, Boris somehow managed to ship 121 kilograms of polaroid films here to save for later use – no customs clerk could believe that this amount of film is for personal, non-commercial projects.

One year later he started working on Long Bien Lovers as part of a group project called The Long Bien Picture Show, of which idea is for each artist to personally respond to the area without having to impose a specific meaning on it. With his broken Vietnamese, Boris went around asking people to let him photograph them with his bulky Linhof camera and a Xenon flashlight. Whether they chose to pose or act naturally, the requirement was that they hold still for the exposure time of one minute. The results are fanciful portraits with dreamy yellow light from the lampposts, long threads of light from busy traffic and the glow from the flashlight that Boris used to illuminate his subjects.

Boris does not have much to say about the project, be it his artistic idea or the social significance. Neither does he recollect how exactly he managed to approach young Vietnamese couples and how they, unfamiliar with a foreign man as well as having their pictures taken at that time, agreed for their intimate moments to be captured. While Boris reinvents the world that he sees with a medium declared dead, the people in his photos are real, alive, and engaging. The photographer simply revels in the joy of interacting with people, making instant pictures, and seeing their surprise upon receiving a print as a gift. “I don’t need to talk, polaroid is a language in itself”. It goes without saying that the magic of polaroid is better felt than described.

Boris Zuliani is a French commercial/fashion photographer who has lived in Vietnam and represented by NOI pictures since 2007. He works with medium and large formats, both film and digital. In his free time, Boris shoots his personal projects using all types of Polaroid instant film, capturing images of people in numerous places around the world. In 2010 Boris was chosen as one of a few photographers in the world to be a part of The Impossible Project, an organization that is dedicated to restore and revive the use of Polaroid film.

Connect with Boris on Instagram.