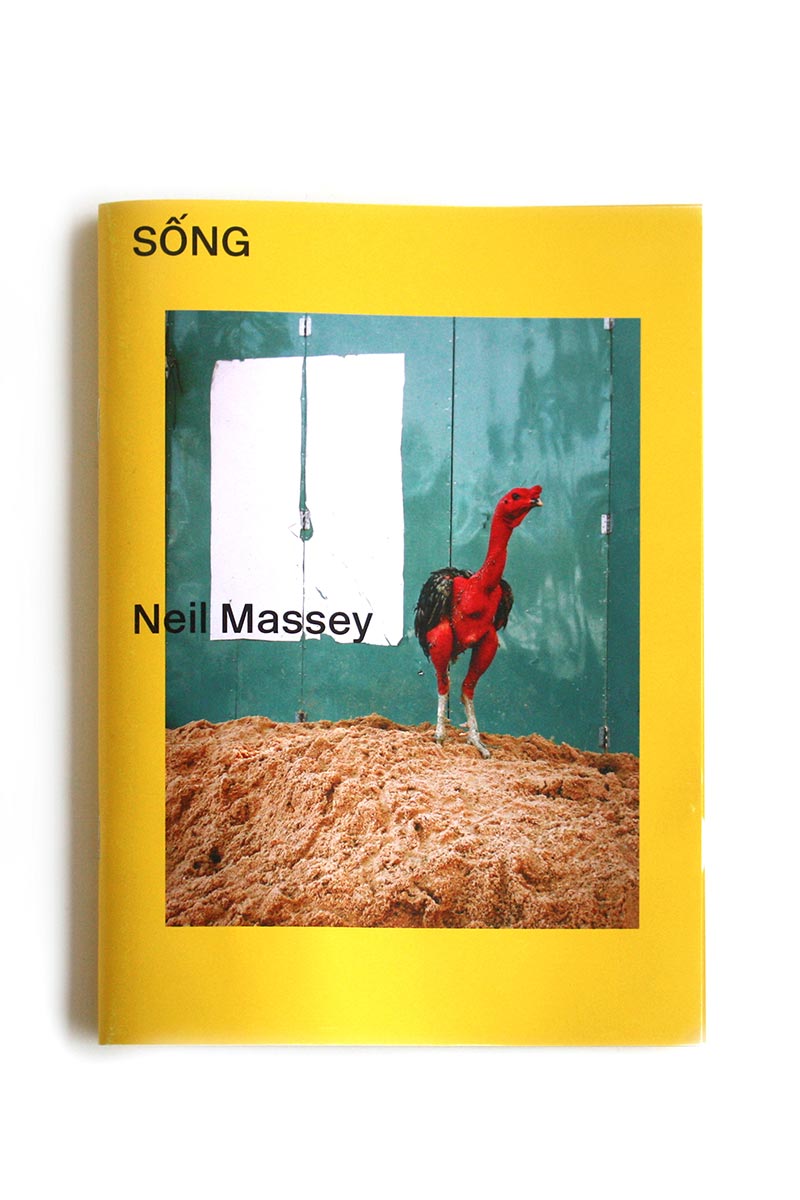

A scarlet fighting cock standing triumphantly on a pile of construction sand, colorful sets of plastic tables and chairs waiting to serve workers, friends and lovers, heavily-tattooed young people lost in a sonic trance. What British photographer Neil Massey has seen during his time in Vietnam bears little resemblance to the often seen image of a tranquil, timeless getaway destination. For 6 years, Neil has chronicled DYI metal shows, sipped iced tea on makeshift street tea stalls and wandered around places existing somewhere between public and private.

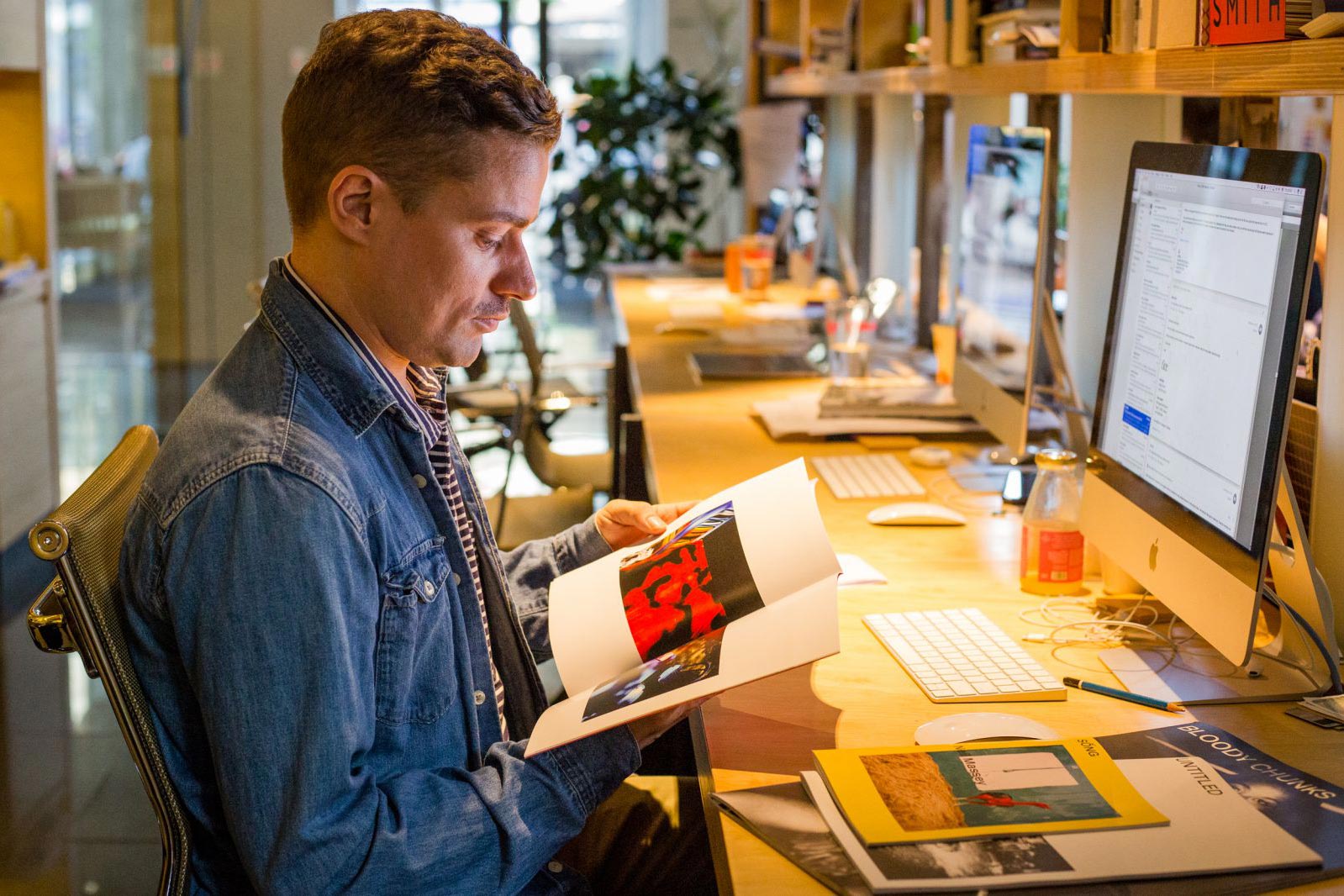

His first self-published work The Vietnam Collection has launched at indie artbook store inpages last Friday. It is a creative collaboration between Neil and Rice Creative, the studio trusted to understand the Saigonese spirit and the artist himself. On designing a photographic work that aims to depict a country, designer Mark Bain shares: “We had no intention of expressing any sort of Vietnamese characteristic or symbolism through design. Any cultural reference or depiction would be held solely in the photography”.

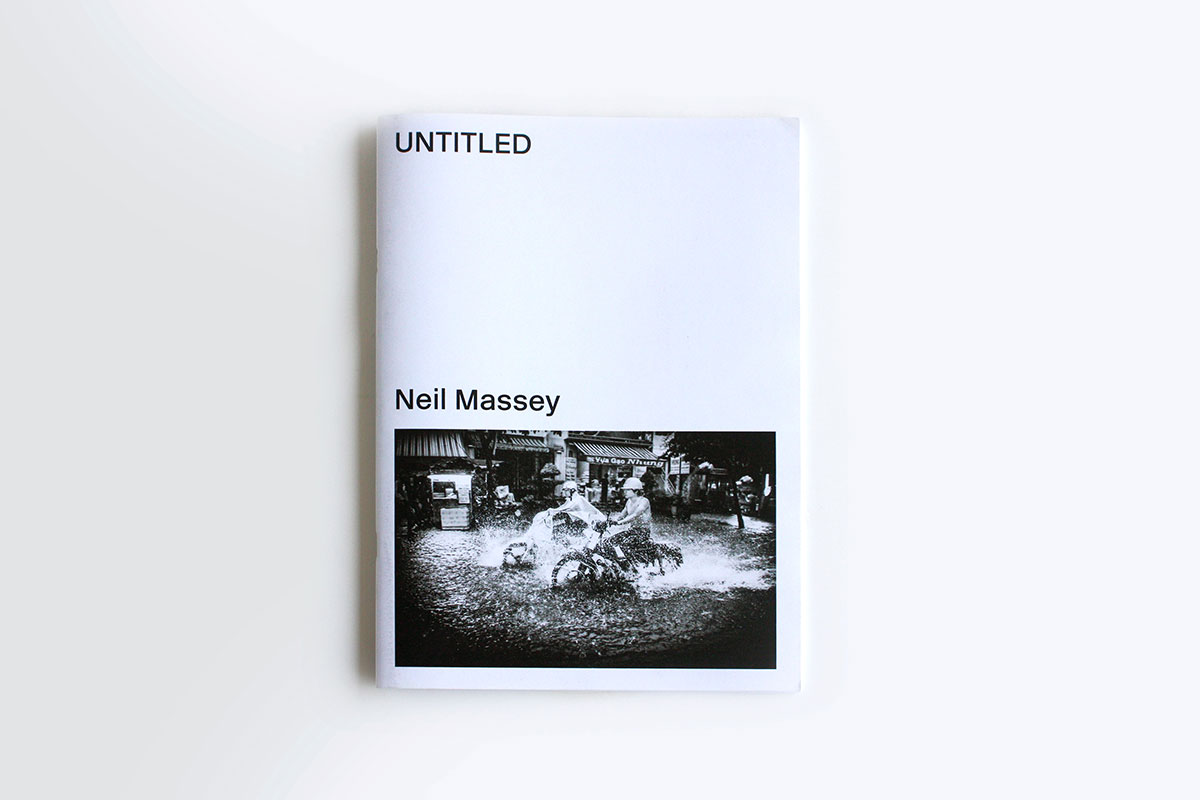

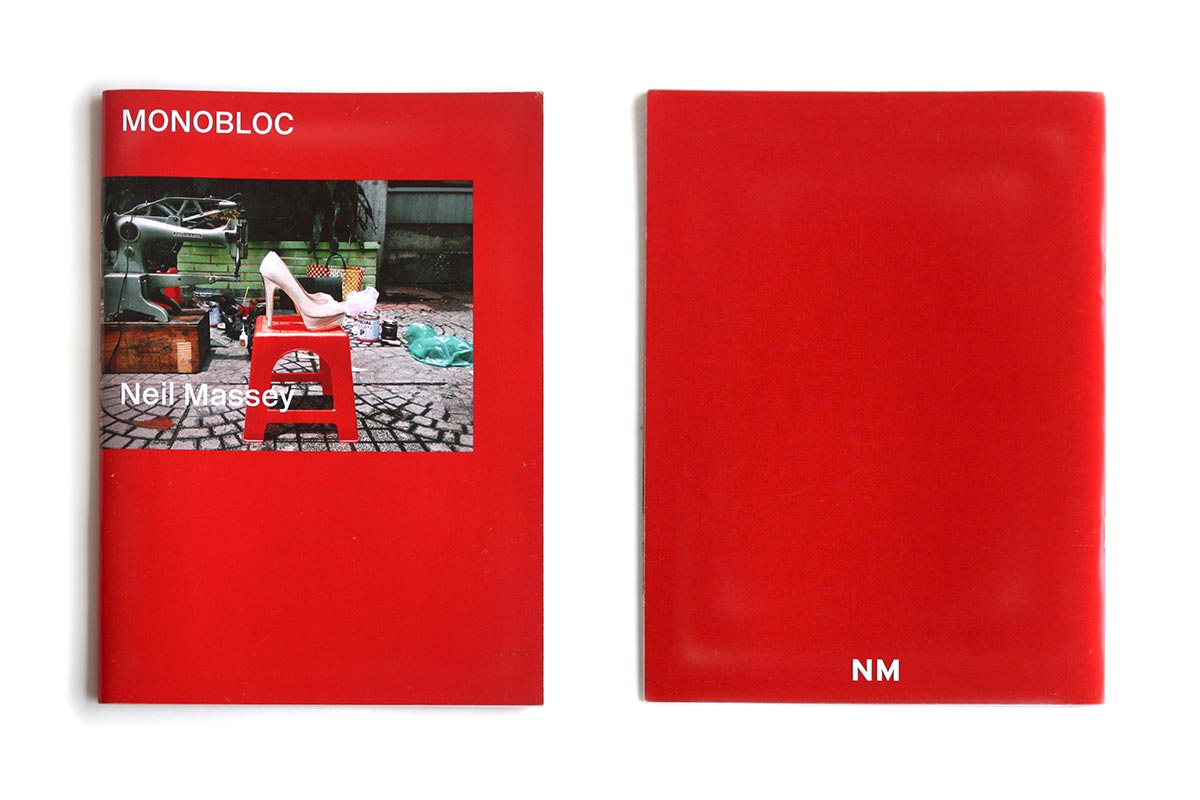

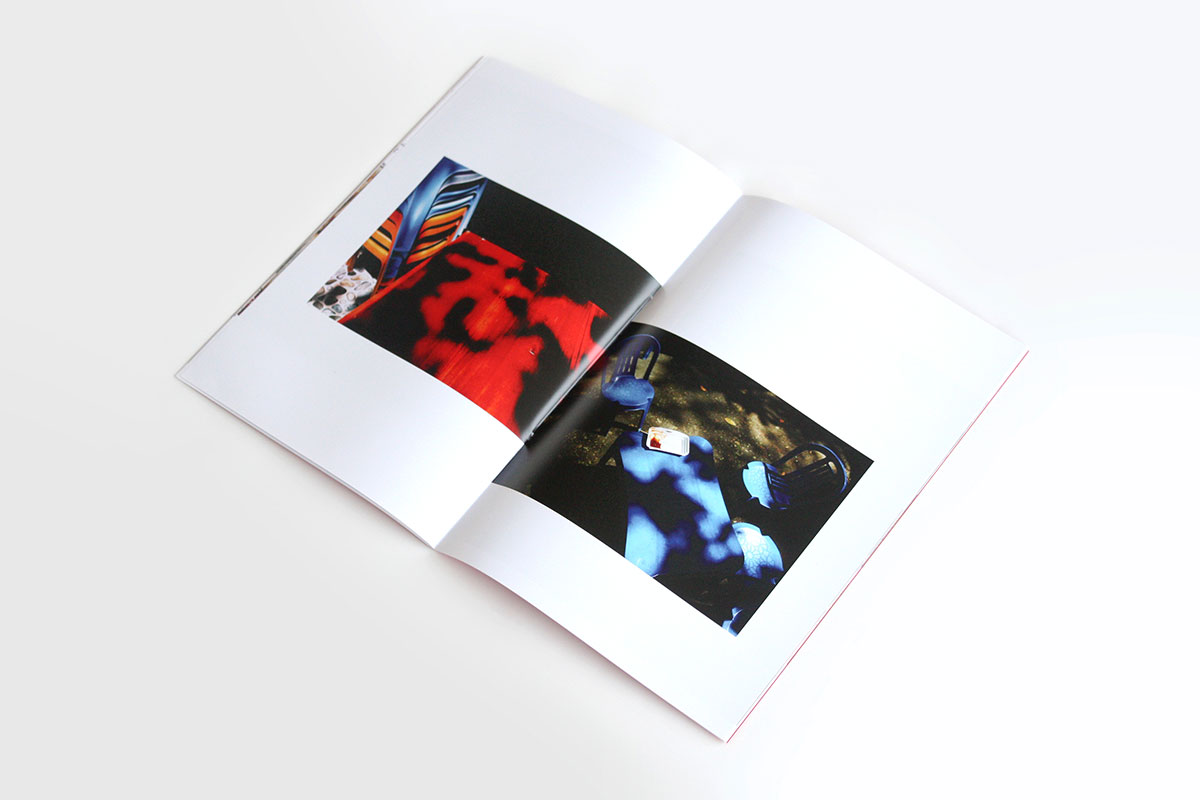

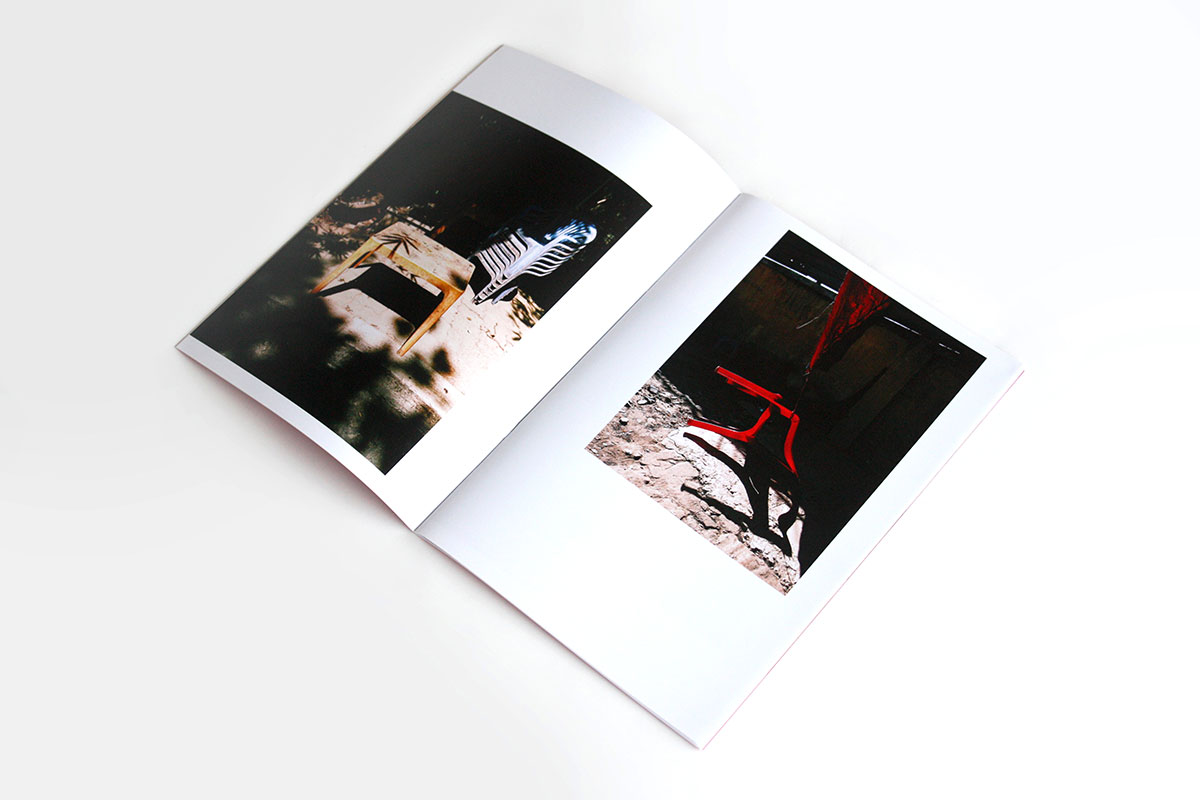

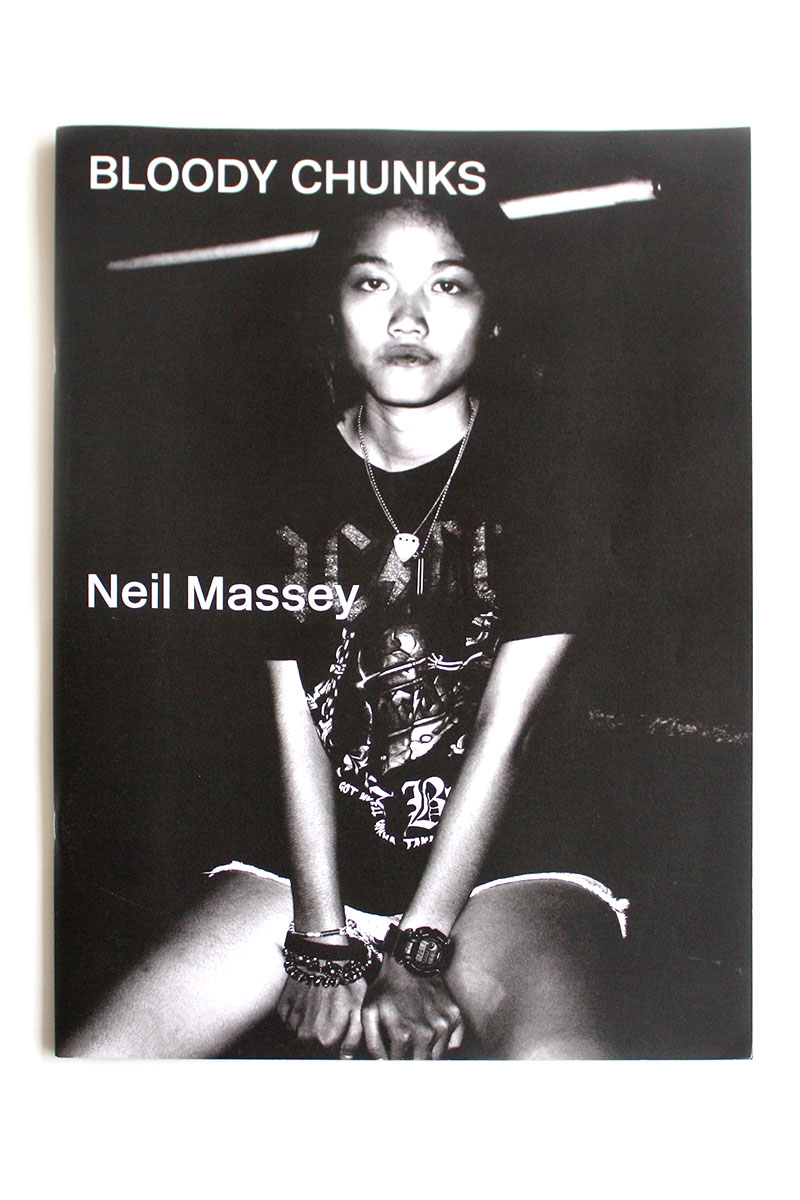

The final results are 4 books of varying sizes, solid color with the robust, clean-cut New Rail Alphabet typeface that contains no Vietnamese symbolism. In conjunction with the consistent typographic approach, the chosen colors unifies 4 books as a collection. Black suits the secretive world in Bloody Chunks, white accompanies the quiet, brooding moments in Untitled, red coincides with vibrant plastic furniture in Monobloc and yellow embraces the vibrant beauty within Sống. Let’s explore Neil’s vision of a loud and noisy but no less charming Vietnam.

From your work, I assume you prefer chaos to tranquility—is that correct? How do you see and adapt to the chaos of Vietnam that has troubled many expats?

I wouldn’t say I prefer chaos to tranquility. I would say Saigon, where I lived for 6 years, had a very special chaotic energy that inspired me. The Vietnamese people have a great spirit and I wanted to convey that. I wanted to show a Vietnam that I was experiencing on a daily basis, not a stereotypical idea of Vietnam. Even though my images can be seen as raw, I like to think there’s a beauty in this rawness. By the way I’m not adverse to some tranquility in my life (laugh).

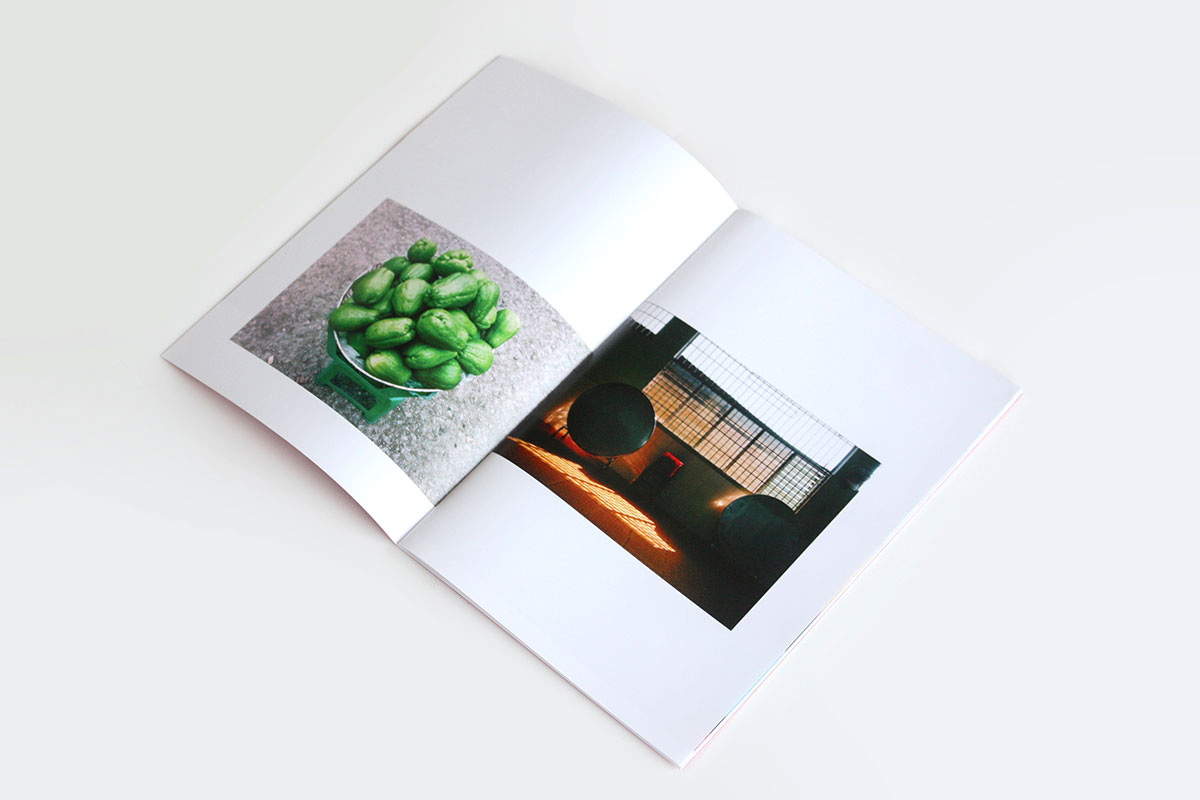

Let’s start with Monobloc, your ode to Vietnam’s plastic tables and chairs. Despite or because of their ubiquitous presence on the street, they don’t receive much attention or speculation. What do you see in the bright colored, cheap and temporary furniture?

The Monobloc series started when I photographed a group of plastic chairs and tables, ready and waiting for the next set of customers. In this moment I saw these brightly coloured objects as subjects, as characters with personalities, each formation with their own story. The way they are randomly laid out each morning by the vendor, reminded me of working, functioning, transitory installations – the vendor an unknowing curator.

What other things do you look for on the street? Your Sống zine is a collection of visual poems heavy with symbolism. Can you share a favorite picture, a memorable moment in the series?

Most of my work is inspired by the activities that happen on the street. My work is an instinctive reaction and intuitive response to life on the street. It’s only later when I look at my work as a whole, I see patterns and themes developing. Whilst editing, the ideas evolve and I focus in on that theme and repetitively shoot this subject over a long period of time. This enables me to study this theme in more depth and develop the idea.

I’m really interested in diptychs and how images work together, so with Sống I was able to play with this idea. Through pairing images together on a double page spread, they take on a new significance which is open to the viewers interpretation. One of my favourite photos is the fish out of water image (which in the book is next to the Tan Son Nhat airport image). I was in Mui Ne with Chi-an from RICE, we were on a fresh fish finding mission for our friends’ dinner that evening. It was a very hot day and this fish somehow flipped itself out of a water tank and onto the street below in front of us—it was a very surreal moment.

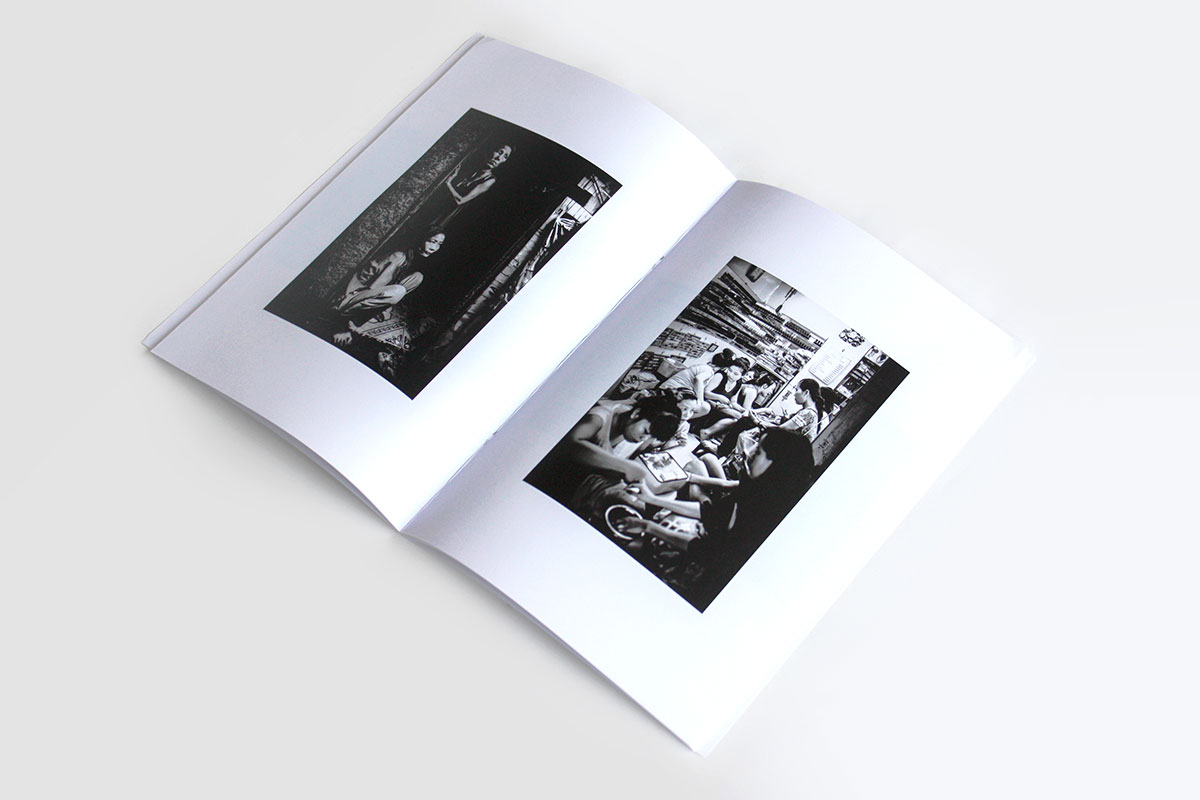

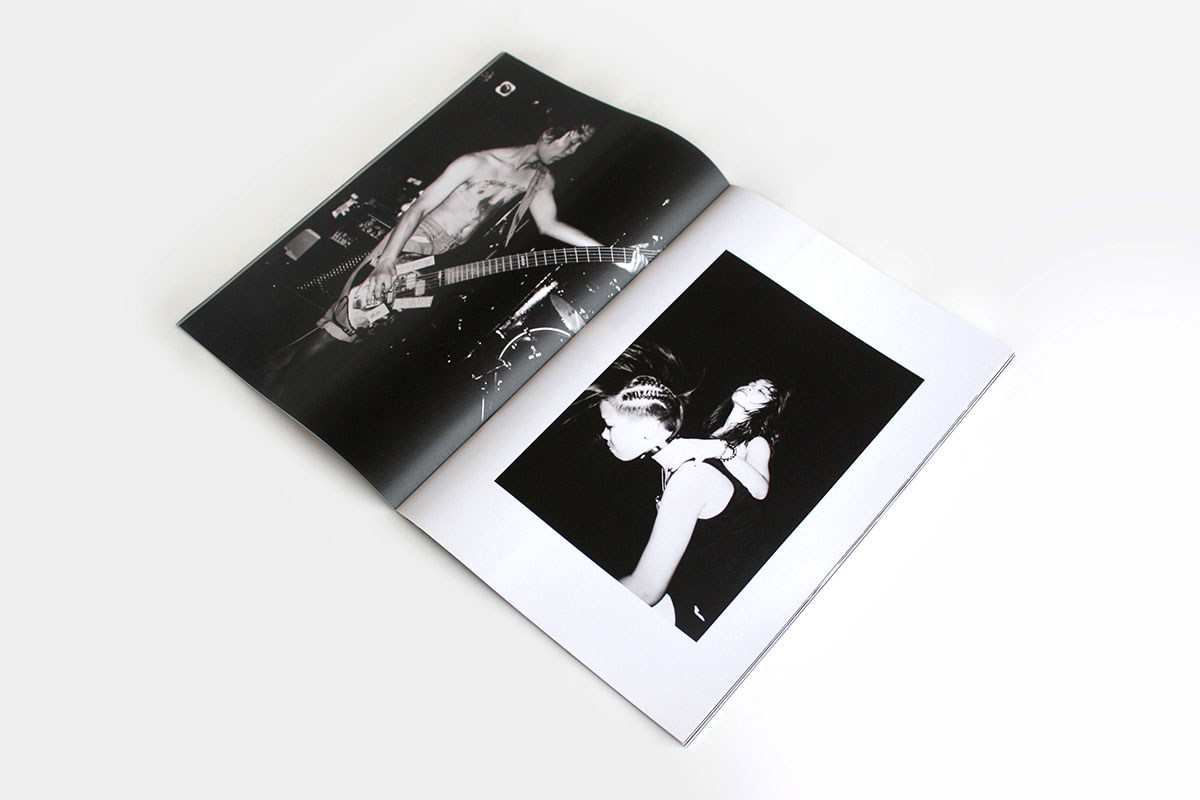

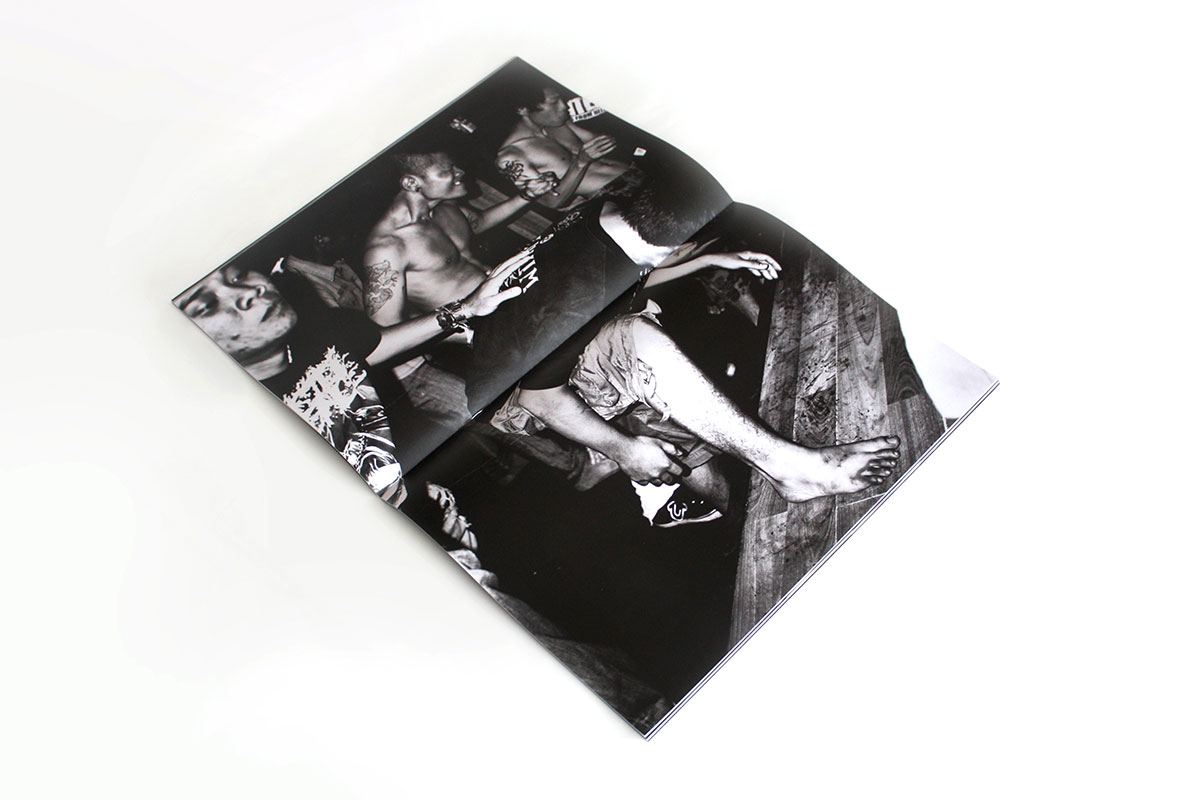

Youth culture is a recurrent theme in your work. You have been photographing concerts and raves from 1999 to 2005, and metalheads in Vietnam from 2009 to 2015. This 6-year project resulted in Bloody Chunks, the largest book in the collection. What insights have you got from immersing in the underground music scene?

I’ve been documenting youth culture since 1990. When I was 19 years old, I spent 3 months travelling around Thailand. I documented the full moon beach raves, the party paradise that inspired the book and film The Beach. In the late 90s I moved to London and started to work for style/youth/music magazines—The Face and Sleazenation. During this time I travelled the world commissioned to shoot musicians and youth cultures. This work makes up the 1999-2005 film collection. All this work was shot on film and is now on show at Boxpark Croydon in London.

I was drawn first and foremost to The Vietnamese Underground Metal Scene, as it reminded me of my experiences at punk gigs in the UK when I was a 15. The hardcore energy and spirit of the metal bands and fans resonated with me. The metalheads were a great bunch of people dedicated to this underground sound and way of life. I admired that, I felt compelled to document this scene, during the years I lived in Vietnam. I always felt great after a gig—the sheer intensity of it. I’ve found over the years that I’ve been documenting youth culture that around the world there are connections—the universal theme of identity, the emotions of being young, experimenting and evolving.

The Bloody Chunks book is A3 in size as its the loudest and most energetic of the 4 books. Myself and Rice wanted the size to reflect that—it should engulf you overpower you when you open it.

Why do you choose the book format to publish these works? Tell us more about your collaboration with Mark from Rice creative, one of the leading creative studios in Vietnam.

I wanted to produce a limited edition run of 100 of each zine/book, signed and numbered. Rather than publish 4 hardback books over a period of years i wanted them all to come out at the same time together. From a design perspective, we really liked how this format seemed best suited to tell these 4 stories, we thought they worked well together as a set or as individual titles. Each title has its own personality. The different sizes, colourways and image layout reflect that.

Mark and the Rice team have been amazing throughout this whole process, massive respect to him as he’s seen the process through to the end designing all the inpages book launch posters and postcards, all in his signature design style. The process of editing took me about two years. I edited all the images for all the books and got the order and flow of images ready, then I handed over the images to Mark and his team and he came back with cover design, font choices and images layout design on the pages. Hardly anything was changed from Rice’s first design presentation to me over skype from Saigon to me in London, which is a testament to their work. I’ve got nothing but great words to say about Rice—it was the perfect collaboration.

I just want to say a big thank you to Long and team at inpages for working with me to launch and stock my books, limited edition prints and posters.

Neil Massey is a British photographer who has worked in HCMC from 2009 to 2015 and now based in London. His four books The Vietnam Collection are finished and published recently. Neil with his wife Julia Massey, a producer, are working together on the Vietnam KIN Project that aims to collect photos from the 1950s to the 1970s and give them back to their rightful owner.

Connect with Neil Massey on Instagram.

Rice Creative is an award-winning branding and creative studio set up in Saigon in 2011. Their young, multicultural team are the ones behind many original identity and packaging system design including Marou Chocolate and Uber.

View more of their works on Facebook & Instagram.