MATCAxC4 JOURNAL: Conversations Around Photography, Vietnam & UK

A series of articles discussing various aspects of image-making. Supported by British Council Vietnam’s Digital Arts Showcasing grant 2021.

????✍️??

The country of Indonesia is composed of over 17,000 islands scattered between the Indian and Pacific oceans. Twelve hundred miles east of Java, which hosts the country’s capital, lies a cluster of a dozen volcanic islets that form the Banda Islands. The tiny archipelago was, for many centuries, the sole source of a spice that prompted the establishment of Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia: nutmeg. The atrocities of colonization, briefly covered in history lessons in junior high school, kept bugging photographer Muhammad Fadli. “How could Westerners travel such great distances to hunt and massacre for a spice?”, he asked, reflecting on boat trips in rough seas from Jarkata to Banda.

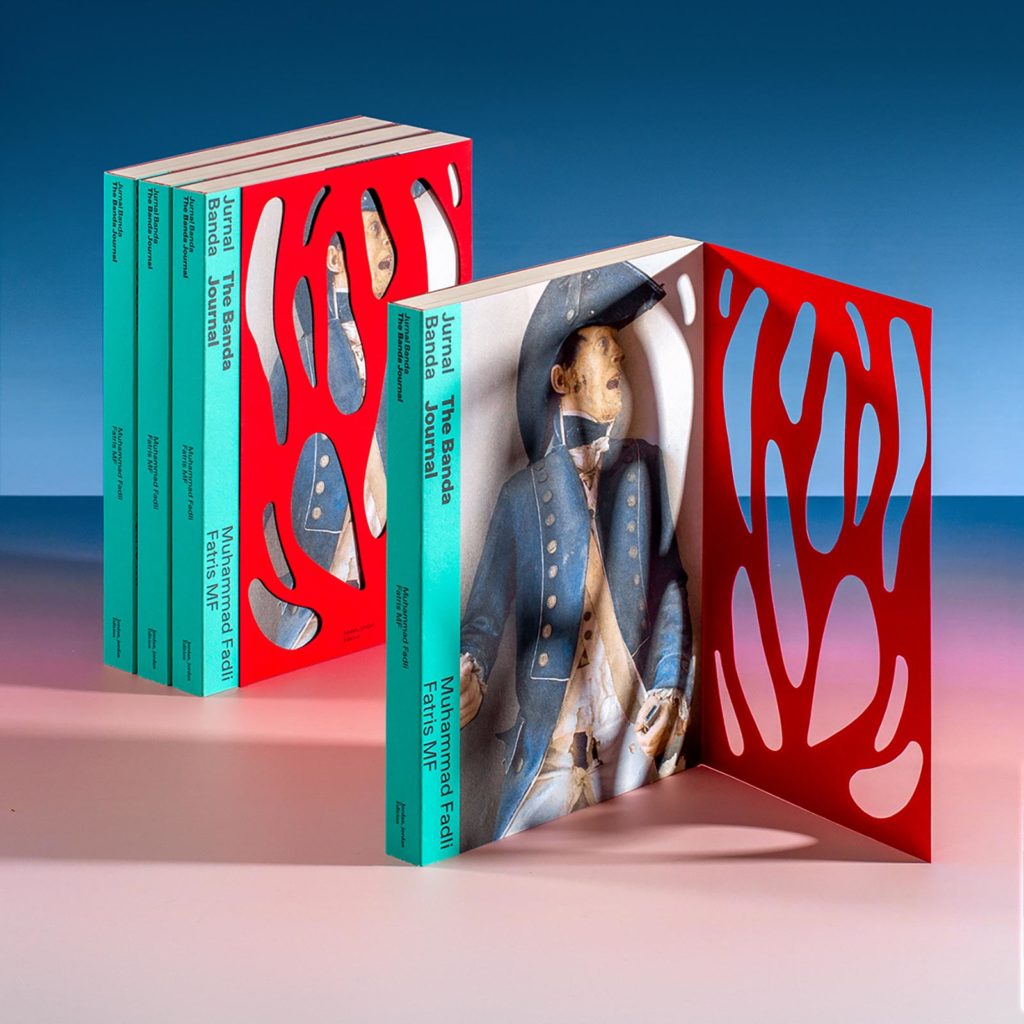

Fadli finally set foot on Banda in 2014, joining fellow journalist and travel writer Fatris MF. The duo then embarked on a collaborative documentary project enquiring into Banda’s colonial history and its long-lasting impacts on local residents. Three years and 150 film rolls later, The Banda Journal materialized into a book published by the local independent publisher Jordan, jordan Édition, and recently won the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year.

Taking the form of a travel journal with eight chapters, the book captivates us from the very cover: a fractured figure of a British Royal Navy officer is wrapped in a striking red web-like pattern, hinting at the skin of nutmeg and past bloodshed. Essays, notes from the road, students’ letters are interlaced with portraits of present-day islanders and lush landscapes.

Through an online interview, Fadli shared in detail about the book-making process, their position as documentarians rather than historians, the virtue of taking it slow, and the fundamental communal aspect of the project.

The project was first intended to be published online in a multimedia format. What was the motivation behind your initial preference for digital publishing?

When Fatris and I decided to work on the project, we saw many examples of how multimedia was used to deliver strong storytelling, and thought that could be effective for this story. I hesitated to think about making a book because for me, the photobook culture here remains mostly confined within photography circles. I was not interested in doing a photography project only to be shown to my fellow photographers. We want the story to be accessible to a large audience. Now that the book has been published, we will still release the project on the website as well.

Could you tell us about the design process? The book contains a considerable amount of text intertwined with the images and it would seem insufficient to consider it solely as a photobook.

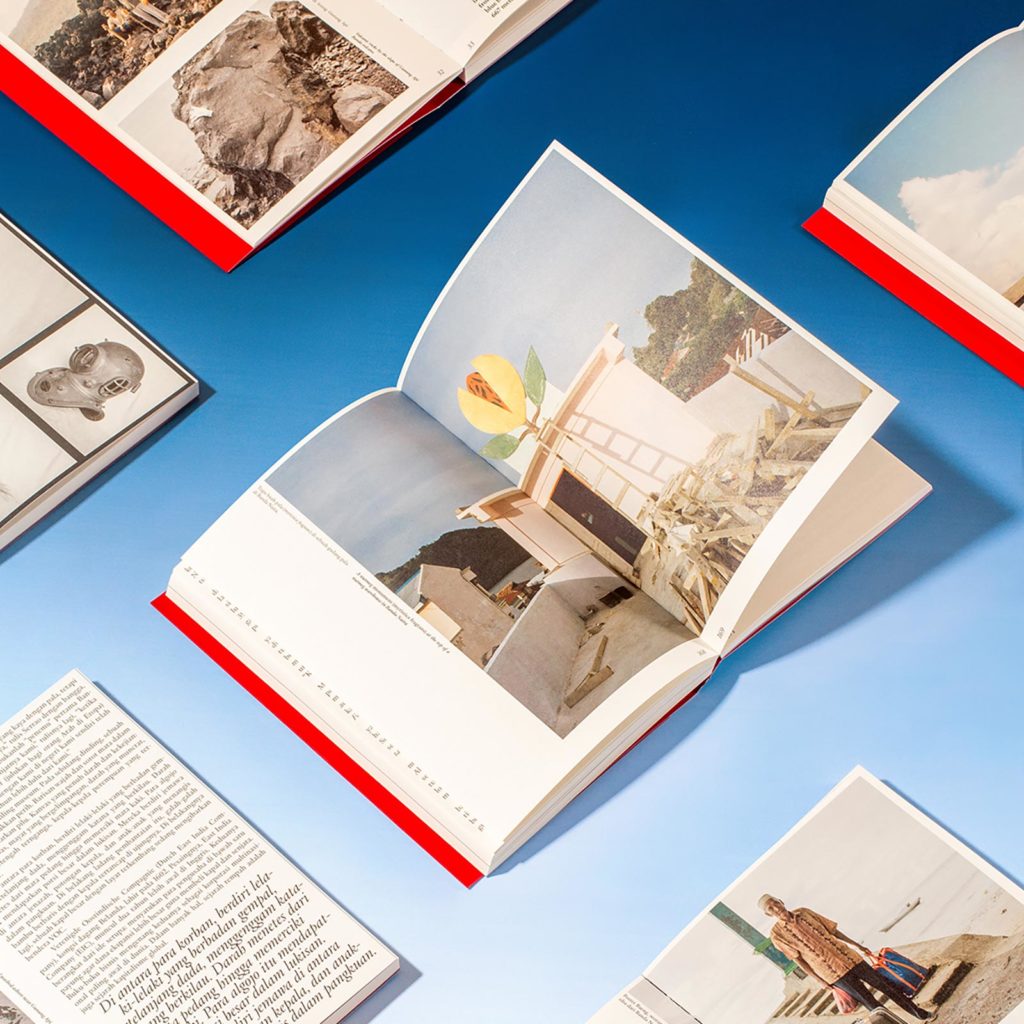

From the very beginning, designer Jordan Marzuki and I have discussed how the book would be read by people. We had no desire to make a coffee table book. We’d like people to actually read it and not simply browse through the pictures.

With that in mind, we use book paper to offer a pleasant reading experience. We sacrifice a little in terms of picture production, but that’s not a big deal at all because the images don’t take centre stage in this book. It’s not whether I as a photographer or Fatris as a writer has a more significant role. The essential thing is to tell the story, whether through the photos, the text or the design. The design is very functional. Every aspect of the book that you see serves a storytelling purpose.

My initial idea was for the main text to be written in Indonesian language and the English translation printed in a small separate booklet, but Jordan pointed out that no one would read that and decided to make the book bilingual. Indonesian and international audiences are equally important to us, since the story is relevant to anyone interested in the history of colonization and the modern economy.

The experience was rewarding for me not in terms of achievement but on a personal level. Sometimes, as a photographer, you might be too focused on your professional goals and forget about making connections as a human being.

Muhammad Fadli

Although the story deals with history, why did you choose not to integrate any archival photos into the book?

Our core intention is to make the story understandable to the general public, including young readers. As we’re no experts in playing with archives, we don’t want to introduce materials that might be too complicated. If we consider ourselves as artists and experiment too much, our work may lose intelligibility. Many people in Banda helped us in this project, so we have to try our best to deliver the story because we owe that to them.

The final pages present a series of scanned letters written by Bandanese students, which I think is a kind of archive in the making.

Upon Fatris’ first visit to Banda, he was invited to teach at a local junior high school. There, he gave the students an assignment where they would write in any form, a letter or prose, about their daily life. The resulting texts reveal how the young Bandanese see themselves – how they think, how they have fun after school, their hopes and dreams, which I think would be impossible to get in any other way. Normally, it isn’t quite obvious for us Indonesians to articulate ourselves. Writing provides these students a medium to express themselves, which also allows the readers to get immersed in the Bandanese mind.

In many parts of Southeast Asia, the introduction of photography was intrinsically linked to colonialism. You raised the question of whether it is “possible to use the same tools [employed by colonizers for their agenda] to achieve a different result”. How did you put that idea into practice?

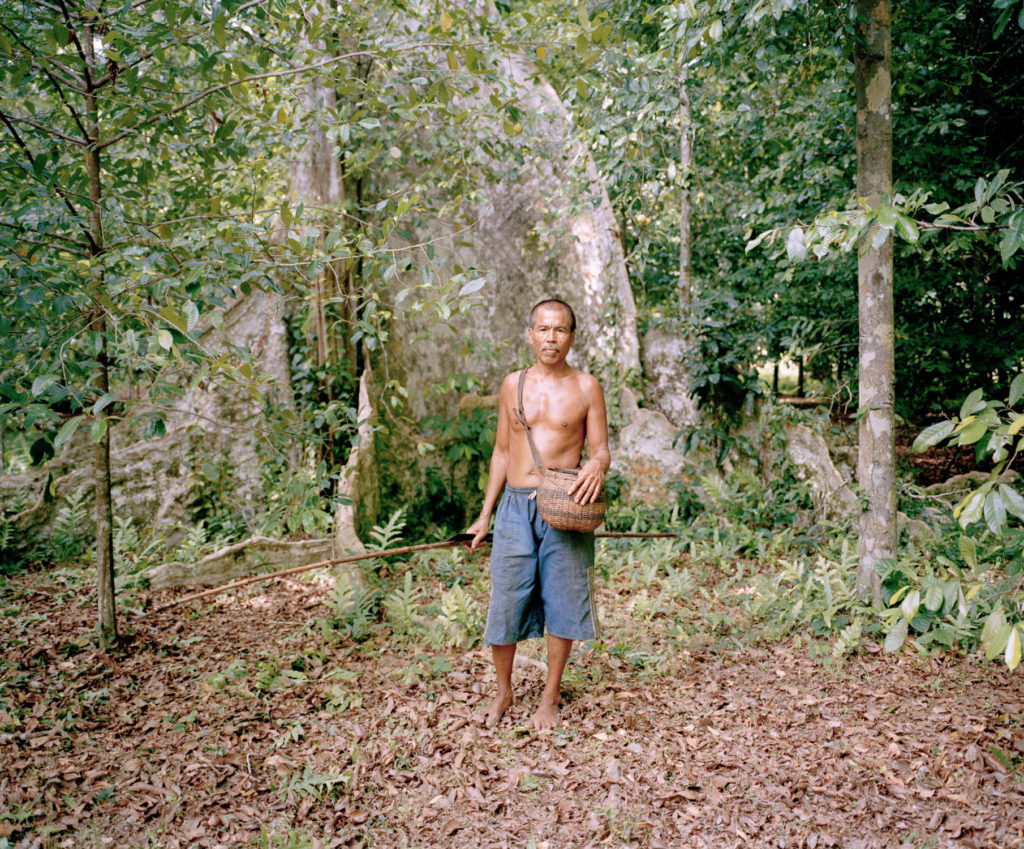

We can have the intention to achieve a different result, but the result could still not match our intention. So we have to keep questioning what we do and the image-making process itself. The camera that I used was not suitable to capture actions. My pictures of the locals are mostly portraits, which sometimes even look staged. I’d like my pictures to empower people.

The questioning does not concern photography alone but also writing. In the text, we try to include people’s voices as much as possible. For example, the last chapter “Song From Another Land” seeks to recount the story of the descendants of the indigenous Bandanese [who survived the 1621 massacre and retreated to other islands in the Maluku archipelago], how they pass down their ancestral culture and language through songs, without any written account. We quote passages from Western texts as well to highlight the vision that the Westerners had of Banda at that time and compare it with local perspectives. It’s not like we’re the ones who produce the work here; rather, we’re letting ourselves become a bridge.

You and Fatris have been working together for a long time, covering travel stories for magazines. In what way is your approach in this project different from your professional work?

For this project, we had no obligation about timing. We could stay as long as we wanted, so we took everything really slow. I was never in a rush to get something. I would talk to people first, visit their homes, and make a lot of friends.

Banda is highly cosmopolitan, a characteristic shaped precisely by its colonization. After the massacre of the original Bandanese in 1621 [as part of the Dutch conquest to establish their monopoly on the spice trade], the Dutch repopulated the islands with slave workers originated from various places across the Malay Archipelago as it was called then, such as Java, Sumatra, or Sulawesi. The present-day Bandanese are very open to outsiders, probably because they feel that they were immigrants in the first place. They receive you with open hands. In the end, the place ended up feeling like home.

The experience was rewarding for me not in terms of achievement but on a personal level. Sometimes, as a photographer, you might be too focused on your professional goals and forget about making connections as a human being. The process of working on this project has changed the way I approach and collaborate with people.

Was your decision to shoot on film motivated by this slowness?

It wasn’t really a choice. During my first trip to Banda, because I was not on assignment, I just brought my film camera with me. I had no plan to photograph something specific. Pictures from the first roll came out quite nice and I felt like continuing to do it. It’s a pleasant change when making pictures is not your only intention but merely a part of what you’re doing.

With film, you can’t immediately view the result so you’re forced to keep talking with your subjects. Then you will stay more connected with them and remember more details. It’s a cliche but it’s true. With digital, you’re too busy getting a perfect picture. It’s good to not be able to see what you’re doing on site sometimes.

How do you position yourself in relation to the history of Banda? Are you and Fatris telling this story from an insider or an outsider’s perspective?

I guess we are insiders and outsiders at the same time. We’re insiders because we’re part of the bigger Indonesian community, which is of great diversity. We’re united by the same colonial history – that’s how Indonesia came about as a country, right? But we’re also outsiders because the culture in one area can be very distant from another. This double status allowed us to keep things in balance in this project.

Muhammad Fadli is a Sumatran-born Indonesian photographer based in Jakarta, Indonesia, focusing on documentary and portrait photography. His personal projects explore different themes such as history, subculture, environment, and social issues. He splits his time between editorial assignments, corporate and commercial works, personal projects, and as a father of a young daughter. He is the cofounding member of Arka Project, an independent collective of Indonesian photographers, and also a Climate Change reporting fellow of The GroundTruth Project.

All photos © Muhammad Fadli